Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (9 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

E

arly the next morning, Frank Millet took out a sheet of cream White Star notepaper with the line’s red pennant and “On Board R.M.S. ‘Titanic’ ” printed at its top and began penning a letter to his old friend Alfred Parsons. After extolling the comforts of the

Titanic

, Millet described his own accommodations:

I have the best room I have ever had in a ship and it isn’t one of the best either, a great long corridor in which to hang my clothes and a square window as big as the one in the [Russell House] studio alongside the large light. No end of furniture, cupboards, wardrobe, dressing table, couch, etc., etc.

This description bears no resemblance to cabin E-38, the small, inner room listed as being Millet’s on the passenger list. It is, however, an accurate depiction of Archie Butt’s stateroom, B-38. Archie had paid the same £26 fare as Frank but the White House had pulled strings to have him upgraded to a bigger stateroom. It’s possible that Archie had managed to have his friend transferred to a larger cabin as well, although Millet would not have wanted to pay much extra for it. It’s also possible that Frank may have simply chosen to keep his small cabin for sleeping and use Archie’s larger stateroom during the day for reading and writing. The two men had reportedly shared a cabin on the

Berlin

on the way over in March and had also been housemates in Washington. One of their friends described their closeness as being like that of Damon and Pythias; another noted that “

the two men had a sympathy of mind which was most unusual.” Expressions such as these have led to speculation as to whether a more intimate relationship existed between Frank and Archie.

Of the two men, Archie Butt, the witty, dandified bachelor with an intense devotion to his mother, seems a more likely gay man than Frank Millet, the decorated war correspondent and married father of three. But it is only from Millet that we have tangible proof of same-sex affections. A cache of his love letters to a San Francisco poet and writer named Charles Warren Stoddard have, quite remarkably, survived. They date from 1874, when Millet, then twenty-eight, was enjoying the Bohemian life on the Continent after completing his art studies at the Royal Academy in Antwerp. He had come to Venice that fall to paint and study the Italian masters, particularly Titian. “Charlie” Stoddard, thirty-one, was similarly smitten with wanderlust. During his twenties he had made four voyages to Hawaii and other Pacific islands, and his published account of these journeys,

South Sea Idyls

, contains descriptions of encounters with native men that, to the knowing reader, are unmistakably homoerotic.

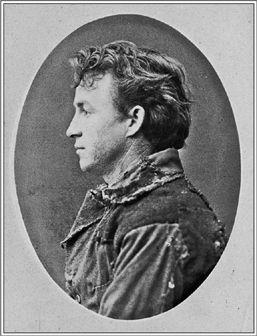

Frank Millet, circa 1874

(photo credit 1.81)

In the autumn of 1874, Stoddard was supporting himself in Europe by writing travel pieces for the

San Francisco Chronicle

. One night at the opera in Venice, a young man quietly joined him in his box at intermission. “

We looked at each other,” Stoddard wrote, “and were acquainted in a minute.” The young man was Frank Millet. He soon asked Stoddard what he was doing for the winter and then suggested they share living quarters. Stoddard accepted the offer and remembered that they became “almost immediately very much better acquainted.”

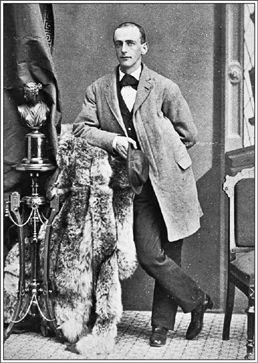

Charles Warren Stoddard

(photo credit 1.10)

It’s possible that Millet had already met Stoddard a few months earlier in Rome through Mark Twain, for whom Stoddard had been a kind of secretary and drinking companion. Frank also needed someone to share the rent for “Casa Bunce,” an eight-room house overlooking the Grand Canal that he had inherited when another artist had decamped for Rome. But Charlie Stoddard would be more than just a roommate to Frank—he became the first, and perhaps greatest, love of Millet’s life, and their Venetian idyll would be fixed forever in his memory. During the daytime hours, Frank labored diligently on his art, sometimes making copies of works in churches or galleries, or sketching in Piazza San Marco. Charlie smoked, napped, and worked in a dilatory way on his articles for the

Chronicle

. In the evening they might take a gondola ride with Giovanni, their gondolier, cook, and errand boy. In his

Chronicle

pieces, Stoddard would switch genders when writing of “

spoons” with “my fair” in a gondola, “… but that is between us two.”

In late January of 1875, the pair left Venice for a three-week tour of northern Italy. In Padua, Frank was entranced by the Giotto frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel, and Stoddard, a Catholic convert, was equally awed by the Basilica of St. Anthony and gave Frank a medallion of the patron saint of lost things. They then moved on to Florence, where they paid an after-hours visit to Michelangelo’s

David

. After bribing the custodian to open a wooden shed behind the Accademia where the statue was being kept, the two men climbed some wooden scaffolding to a platform surrounding the figure’s waist. Frank ran his fingers down the swollen veins of the right arm and encouraged Charlie to do the same. He later described

wanting to hug the marble image because it seemed as warm as flesh. Frank had seen the

David

in Florence the year before and had fantasized about touching it with Charlie, perhaps imagining the two of them communing with an artist from an earlier time who shared their affinity for the beauty of men.

They then moved on to Siena, where, according to Stoddard, the two lovers slept in “

a great double bed … so white and plump it looked quite like a gigantic frosted cake—and we were happy.” Not long after their return to Venice, however, the happiness began to pale, at least for Charlie. Money was scarce, and Casa Bunce was drafty and hard to heat, causing Frank to come down with rheumatism. Into this scene out of

La Bohème

there suddenly floated a tall, handsome figure in a long, black cloak of “

Byronic mold” wearing a large hat with tassels. Charlie dubbed him “Monte Cristo,” but he was, in reality, an American artist named A. A. Anderson, who had independent means and a taste for the high life abroad. An entranced Charlie spent days in Anderson’s gondola “reading chatting, writing, dreaming or merely drifting.…” In his suite at the Hotel Danieli Anderson hosted a dinner that to Charlie was “the realization of a sybarite’s dream.” The exotic American would soon leave abruptly for Egypt, and a disappointed Charlie would find life at Casa Bunce to be rather drab in the aftermath. By May, Millet’s “butterfly,” as he dubbed Stoddard, had flown, leaving for Chester, England, and a man he had trysted with a year before.

Millet was utterly bereft and poured out his love and longing for Charlie in letters that only caused his “butterfly” to flutter farther away. “

Miss you? Bet your life,” he wrote. “Put yourself in my place. It isn’t the one who goes away who misses, it is he who stays. Empty chair, empty bed, empty house.” Over the door of Casa Bunce he erected a sign,

UBI BOHEMIA FUIT?

(

WHERE HAS BOHEMIA GONE?

) and in his letters to Charlie continually proposed scenarios where they could re-create “our little Bohemia.” It is rare to find such unabashed male passion freely expressed in nineteenth-century correspondence, and it’s clear from Millet’s letters that in the world of European Bohemia that he had embraced so completely, the strictures of his Massachusetts Puritan heritage held little sway.

When his strained finances forced a return home to East Bridgewater in the fall of 1875, Frank’s letters to Charlie took on a near-obsessive tone as he longed for Europe and Charlie and despaired at the provincialism surrounding him. But it would not be until January of 1877 that his finances permitted him to return to the Old World. Traveling with him to France were the two sisters of his Harvard friend Royal Merrill, along with their mother and a younger brother. While a student, Frank had lived with the Merrill family for a year in Cambridge. In Paris, he would share living quarters with them in Montmartre, though even there his longing for Stoddard continued unabated.

“

Come Charlie, come!” he wrote in the spring of ’77. “My bed is very narrow but you can manage to occupy it, I hope.” This invitation was made despite the two Merrill sisters living only one floor below. Stoddard would finally visit at the end of April just as Millet was departing for Bucharest to cover the Russo-Turkish conflict for the

New York Herald

. From Bulgaria, Frank would attempt to stir some jealousy in Stoddard by writing that he was “spooning frightfully with a young Greek here.”

Millet would not return to Paris until mid-April of the following year, arriving sunburned, war-weary, and bearing two crimson military decorations from the Russian czar. The Merrills had eagerly awaited the arrival of “

our hero,” and by the end of 1878, Frank proclaimed himself to be in love with Elizabeth “Lily” Merrill, the elder of the two sisters. His affection for Lily seems to have been heartfelt, but he would prove to be an often-absent husband and an indifferent father. There would never be other women, however, and there are clues in Millet’s short stories and letters to indicate that his sexual attraction to men was more than just a youthful, Bohemian phase.

“Misogynist” was a name often applied to gay men a century ago, and there was certainly a strong streak of misogyny in Millet. He opposed female artists exhibiting at the Chicago Exposition, and even his last letter to Parsons from the

Titanic

is heavily larded with female disparagement. In addition to railing about “obnoxious, ostentatious American women” and proclaiming the young American woman to be “a buster,” he notes that the ship has “

smoking rooms for Ladies and Gents, intended I fancy, to keep the women out of the men’s smoking room which they

infest

in the German and French steamers” [italics mine]. He concludes by calling Olga Mead, the Hungarian wife of architect William Mead, “a B—” [Bitch]. All in all, this reveals more misogyny than can be ascribed to the garden-variety male chauvinism of the period.

Earlier in this rather revealing letter, Millet begins his commentary on the other passengers with a few lines that have always intrigued

Titanic

researchers:

Queer lot of people on this ship. Looking over the [paasenger] list, I only find three or four people I know but there are good many of “our people” I think.…

Although “queer” was already a pejorative term for homosexuality by 1912, Millet was most likely not using it in that context. But who are the “our people” he so enigmatically sets off in inverted commas? If he simply means “our

kind

of people,” why did he not say so? And from his condescending references to the American passengers, it seems clear that Millet thinks most of those on board are

not

his kind of people, nor would they be for a refined Englishman like Alfred Parsons.

Parsons was a key member of the “little Bohemia” that had first formed around the Millet household in Broadway during the summer of 1885. In 1900 Millet had sold to Parsons five acres of his Russell House property, on which he built his own house and garden. First known as an illustrator and painter of English pastoral scenes, Parsons later gained a reputation as a garden designer. He assisted Lawrence Johnston in the creation of Hidcote, today one of England’s most-visited gardens, and designed the grounds for Henry James’s Lamb House in Rye. Like James, Parsons never married and was considered to be a “confirmed bachelor.”

Could Millet therefore mean “our people” to be gay people? Parsons was a very close friend of Millet’s, and it is not impossible that he could be alluding to their shared affinities. It would be decades before anything like a gay identity would emerge in England or America, but from the writings of E. M. Forster, Edward Carpenter, Hugh Walpole, and others, we know that Edwardian gay men did manage to find one another. Can it be merely coincidence that a good number of the artists and writers drawn to Millet’s Broadway Bohemian “colony”—Henry James, John Singer Sargent, Alfred Parsons, Edwin Austin Abbey, and Edmund Gosse—are believed to have had same-sex affections?