Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (39 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Ismay took only soup for dinner that evening in his room—a room, he later insisted, that was merely a storeroom where Dr. McGee kept his medicines, not a private cabin. For many of the other rescued passengers, a search began after dinner for places to sleep. Women with children were given first priority for staterooms and Daisy Spedden noted in her diary that a nice man gave up his cabin to her and her son Douglas, her maid, and Miss Burns, while an elderly gentleman took in her husband, Frederic. Edith Rosenbaum made a bed for herself on one of the tables in the dining saloon while other women slept in the lounges, using sofa cushions as pillows. The men found refuge wherever they could, mainly in the smoking rooms, where they curled up on the floor, the tables, or on the upholstered benches. Norris Williams found that the smoking room benches were not long enough for him to sleep on for any length of time, but this suited him since he was getting up every two hours to exercise his legs anyway.

In the wireless room, the work of transmitting survivors’ names continued, but the young operator, twenty-one-year-old Harold Cottam, was feeling the strain. He had been at his key for the last twenty-four hours and at one point had snapped, “

I can’t do everything at once. Patience please.” Someone told Harold Bride, who was resting in the hospital with a sprained ankle and frostbitten feet, that Cottam was getting a bit “queer.” Bride offered to help and managed to hobble up to the wireless room where he sat on the bed with his foot propped up on a pillow, organizing the traffic while Cottam continued transmitting. That night they passed on 321 names of first- and second-class passengers, promising that the list of third-class passengers and crew would follow the next day. At one point, Cottam said to the

Olympic

’s operator, “Please excuse sending but am half asleep.” One of the names wrongly keyed in due to his fatigue was a “Mr. Mile,” which would cause Frank Millet to be reported as among the survivors the next day. But at Russell House in Broadway, Lily Millet already had a deep sense of foreboding that her husband was gone.

It was not until 6:20 p.m. on the evening of April 15 that a message to the White Star offices in New York from the

Olympic

delivered the shattering news that the

Titanic

had sunk. Philip Franklin was so shocked that it took him several minutes to pull himself together. After telephoning two IMM directors, one of whom was J. P. Morgan Jr., he went to speak to the waiting reporters. Franklin began reading the

Olympic

’s wireless message aloud but got no further than the second line and the words “

Titanic

foundered at 2:20 a.m.” when the room suddenly emptied out as the newsman charged off to call in the biggest story of the new century.

At 8:00 p.m. President and Mrs. Taft were sitting at Chase’s Theater in Washington, waiting for the curtain to go up on a comedy called

Nobody’s Widow

. A White House messenger arrived with an envelope for the president that was carried into their private box. Within minutes, the first couple had left the theater and were being driven back to the White House. The president went directly to the telegraph office in the executive offices next door and began reading the latest press bulletins. Taft’s round and normally genial face looked ashen, his jowls hung in folds. He telegraphed Philip Franklin to inquire as to whether Major Butt was among the rescued. A similar message was sent to the Marconi station at Cape Race, Newfoundland. Before returning to the White House, Taft asked the telegraph operator to keep him informed of all developments during the night.

THE NEXT MORNING

Lucy Duff Gordon awoke to light streaming in through the portholes and was surprised to find herself in an unfamiliar cabin. A stewardess came in with tea, and on seeing her instead of her Irish stewardess from the

Titanic

, Lucy suddenly remembered where she was. As memories of the disaster flooded back, she buried her face in the pillows and wept. A woman from the next cabin later helped her to dress, and the two of them went out on deck, where they encountered small groups of survivors, all of them discussing the tragedy. “

All that day and for the remainder of the voyage until we arrived in New York,” Lucy wrote, “the

Carpathia

was a ship of sorrow as nearly all were grieving over the loss of somebody.”

At breakfast in the first-class dining saloon, Margaret Brown suggested to those at her table that a fund should be started for “

the poor foreigners who, with everything lost, would be friendless in a strange country.” This met with a positive response though Margaret soon found that not many of the men were willing to actually pledge money to her idea. But there was general agreement among the survivors that a fund should be started to express the gratitude of the rescued to Captain Rostron and his crew. At a meeting held at three that afternoon in the dining saloon, almost all of the cabin-class survivors turned up and $4,000 was pledged on the spot. It was agreed, however, that the needs of the destitute should be met first, and Margaret Brown, her friend Emma Bucknell, and two others were appointed to a committee for that purpose. A resolution of thanks to God and to the captain and his crew was drafted and signed by the newly formed Committee of Survivors, which included, among others, Karl Behr, Mauritz Björnström-Steffansson, Algernon Barkworth, Isaac Frauenthal, Frederic Spedden, and Frederic Seward, with Margaret Brown as its sole woman. The resolution also promised to thank the

Carpathia

’s officers and crew in a more tangible way and by Thursday approximately $10,000 had been raised. Money was distributed to the captain and crew before landing, and a silver cup for the captain and medals for the officers and crew would be presented when the

Carpathia

returned from the Mediterranean in late May.

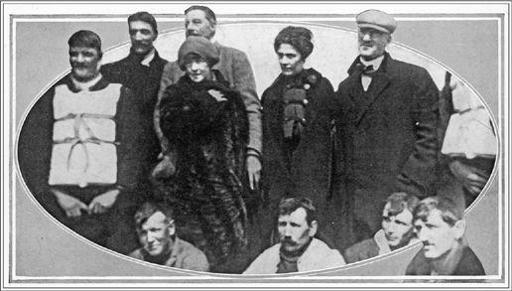

In this spirit of giving, Cosmo Duff Gordon remembered that he had promised “a fiver” to the men in Lifeboat 1. Since he was without his checkbook he asked Franks to find some notepaper and write out bank drafts for him. The Duff Gordons then arranged for a presentation on deck and asked the crewmen to wear their lifebelts—causing alarm among several women when they appeared carrying them. Lucy brought along her lifebelt so that everyone could sign it as a souvenir. Group photographs of the twelve survivors from Boat 1 were then taken by a

Carpathia

passenger, Dr. Frank Blackmarr. A number of those on deck at the time thought the whole occasion was inappropriate—a few even claimed that someone called out “Smile!” as the photo was being snapped, which is likely untrue. But it did fuel rumors that “the lord and lady” had escaped in their own private boat, a story that would be repeated once they were ashore.

Edith Rosenbaum, however, was completely won over when she finally met the famous Lucile in person. “

Are you the one giving such interesting reviews in

Women’s Wear

?” Lucy asked Edith and then told her how much she had admired her stylish clothes on the

Titanic

. Edith recorded that they swapped fashion information and that Lucy regretted that “all her models [designs], as well as my own, had gone to the bottom of the sea, but we acknowledged that pannier skirts and Robespierre collars are at a discount in mid-ocean.”

The small contingent from Lifeboat 1 poses for a souvenir photograph. Lucy stands at center, in front of Cosmo, and beside Mabel Francatelli.

(photo credit 1.58)

Dorothy Gibson also found that new apparel was difficult to come by in mid-ocean and so continued to wear the white silk evening dress she had donned for dinner on Sunday night. The prettiest girl sported a large diamond ring on her engagement finger, given to her by Jules Brulatour, the head of Eastman Kodak and an investor in Éclair Films, who was planning to marry Dorothy as soon as he could divorce his wife. There is a twinge of disappointment in William Sloper’s account as he acknowledges this. Sloper had seen Alice Fortune (whom he had once called his “

Canadian girlfriend”) come aboard from the lifeboat with her sisters and their mother, Mary, who was in a state of near collapse. A sympathetic Dr. McGee had arranged for the Fortunes to use his cabin and an adjoining consulting room. Not wanting to intrude on their grief, Sloper left Alice alone until Thursday when he knocked on her cabin door to offer assistance in finding accommodation in New York. With a tear-stained face, Alice assured him that they were being met by friends from Winnipeg. Just before closing the door, she reminded him of the prediction made by the fortune-teller in Cairo.

Norris Williams finally became acquainted with Karl Behr on the rescue ship and recalled that Behr and Helen Newsom and the Beckwiths were very kind to him. By taking walks every two hours, Norris felt his legs improve each day, and a few months later he was back on the tennis circuit. In 1914 he and Behr would compete together on the U.S Davis Cup team, and Williams would also become a U.S. singles champion, a Wimbledon doubles champion, and an Olympic gold medalist. Norris met another survivor on board who told him that he had been bringing home a prized dog on the

Titanic

and had gone to the kennels and released all the dogs a half hour before the ship went under. Norris described to him how when he was swimming away from the sinking liner he had spied the black face of a French bulldog in the water. This was no doubt Gamin de Pycombe, the French bulldog that Edith Rosenbaum had tucked into bed in Robert Daniel’s stateroom after the collision. Daniel himself was rescued from the water, though his bulldog was not. The fact that three dogs had been saved from the

Titanic

when people were lost was a touchy subject among the survivors. On seeing a man (likely Henry Harper) cuddling his dog on deck, May Futrelle described him as the kind of man who would rather save a dog than a child. In addition to Harper’s Pekingese and Margaret Hays’s “little doggie,” the third surviving canine was Elizabeth Rothschild’s Pomeranian, carried by her into Boat 6.

Norris Williams made a full recovery from his ordeal and became a tennis champion.

(photo credit 1.47)

ON TUESDAY NIGHT

a violent thunderstorm broke over the

Carpathia

. Karl Behr was jolted awake by a deafening crash and thought the ship had struck an iceberg. His immediate thought was to find Helen Newsom, and so he raced out onto the deck. There he saw flashes of lightning and with great relief returned to his bed on a smoking room table. Others who awoke to the lightning thought that distress rockets were once again being fired. The storm was followed by rain and fog that lasted for the next two days. This dismal weather kept most people indoors, and the mournful blasts of the foghorn on Wednesday seemed to echo the doleful mood on the “ship of sorrow.” Crowded into the public rooms, there was little for the survivors to do but talk—and talk they did. Accounts of the disaster were repeated and embellished with each telling. But one of the most disturbing stories would prove to be true. Emily Ryerson described to Mahala Douglas and some others how Bruce Ismay had showed her an ice warning message on Sunday and told her they were going to put on more speed. The news that ice warnings had been received and the ship had not slowed down spread quickly, and a group that included Lawrence Beesley sought out one of the surviving officers, who confirmed that this was indeed the case. Learning that the collision could have been avoided filled Beesley with a sense of hopelessness. And resentment toward Bruce Ismay, who remained secluded in his cabin, continued to grow.

With a historian’s eye, Archibald Gracie attempted to separate truth from fantasy as he listened to the survivors’ stories, a potential book beginning to form in his mind. Second Officer Lightoller and Third Officer Pitman regularly stopped by the small cabin Gracie shared with Hugh Woolner to discuss various aspects of the disaster. All agreed that the explosions heard during the sinking could not have been the ship’s boilers blowing up. From the discovery of the severed wreck in 1985 we now know that the “explosions” were actually the sound of the ship being wrenched apart. But Gracie and Lightoller firmly believed that the ship had sunk intact—a view that would become the prevailing opinion for the next seventy-three years. Gracie thought that Norris Williams and Jack Thayer, “

the two young men cited as authority … of the break-in-two theory,” had confused the falling funnel for the ship breaking apart. But both Williams and Thayer knew exactly what they had seen, as did some other eyewitnesses. On the

Carpathia

, Jack Thayer described the stages of the ship’s sinking and breaking apart to Lewis Skidmore, a Brooklyn art teacher, who drew sketches that were later featured in many newspapers. The inaccuracies in Skidmore’s drawings, however, only bolstered the belief that the ship had, in fact, sunk intact.