Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (34 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Norris Williams and his father, meanwhile, were on the bridge with Captain Smith when the ship gave a sudden lurch. Norris glanced down toward the bow but could only see the foremast sticking up from the water like a tree on a floodplain. Suddenly he was engulfed in a torrent of icy seawater that washed over the ship in a wave. As he tried to swim out from the flooded bridge toward the starboard railing, Norris lost sight of his father. As the wave swept aft along the deck, it drenched those who were struggling to cut Collapsible A free from the davit ropes. On the port side, Collapsible B crashed downward and landed upside down on the boat deck.

Archibald Gracie and Jim Smith retreated up the deck from the wave but ran straight into a mass of people streaming out of the first-class entrance from the staircase. The crowd, which included some women, fled aft from the advancing water but was stopped by a railing that marked the end of the first-class promenade. Realizing they were in a tight spot, Gracie and Smith looked up to the roof over the officers’ mess. Smith made a leap for the roof but fell back. Gracie tried, too, but failed, hampered by his heavy coat and lifebelt.

Just then the liner’s foredeck shuddered upward and Norris Williams suddenly found himself standing high and dry on the boat deck as the water retreated. He glanced around and saw his father about twelve to fifteen feet away from him. As the word “suction” flashed into his brain, Norris yelled out “Quick! Jump!” to his father and then leapt over the rail. Others nearby did the same. At about this time, Marconi operator Harold Bride claimed that he looked down from the roof and saw Captain Smith dive into the sea from the bridge.

A moment later the ship’s bow lurched downward again, sending an even larger wave rolling aft. Harold Bride was now on the deck beside overturned Collapsible B and when the water surged toward him, he grabbed an oarlock and held on as the boat was swept from the deck. On the starboard side, a number of people had clambered into Collapsible A and two men were struggling to cut it free just as the second wave washed over it. The boat was slammed against the davit and then pushed toward the forward funnel before it drifted off half-submerged with a few occupants still inside it.

Archibald Gracie threw himself into the second wave as if riding the surf at the seashore. It lifted him up to the top of the officers’ mess where he grabbed the railing, pulled himself onto the roof, and scuttled over on his stomach to the base of the second funnel. When he raised his head to look for Jim Smith, he couldn’t see him or any of the others who had been on the deck only seconds before. Gracie felt a pang of guilt at being separated from his friend since they had agreed to stick together till the end. He thought that Smith might have been thrown against the wall and knocked out or washed overboard in a tangle of ropes and other debris.

Charles Lightoller scrambled toward the wheelhouse roof and dived into the sea. The icy water felt as if a thousand knives were being driven into his body. On surfacing, he saw the crow’s nest on the foremast standing straight ahead of him. His first instinct was to swim toward it, but he quickly realized the folly of clinging to any part of the ship. As he started to swim away to starboard he was suddenly thrown against a ventilator shaft by a rush of water pouring down into it. He knew that the shaft went straight down to a stokehold and that the flimsy wire grating over it was all that stood between him and a hundred-foot drop. Yet each time he tried to struggle free he was pulled back against the grating. He began to feel himself drowning and sensed he had only minutes to live. Suddenly, a blast of hot air shot up the shaft and blew him free. He came to the surface gasping for air but was soon pulled down again by another inrush of water. When he finally managed to struggle away he found himself alongside overturned Collapsible B. A number of men were clinging to its back but the exhausted Lightoller could only grasp a piece of rope and float alongside it. Around him, many others floundered in the water, some swimming, others drowning, in what he called “

an utter nightmare of both sight and sound.”

As the

Titanic

’s bow sank lower, Lightoller could see the stern rising out of the water, “piling the people into helpless heaps around the steep decks, and by the score into the icy water.” He saw the mooring cables to the first funnel strain and then snap, sending the giant funnel crashing down in a shower of sparks and soot. The cable held on slightly longer on the starboard side, which pulled the funnel in that direction, causing it to come down among scores of swimmers, missing Lightoller only by inches. Norris Williams was sure that his father had been killed by it. The funnel’s fall also caused a wave that pushed overturned Collapsible B away from the ship, with Lightoller still holding on to its rope.

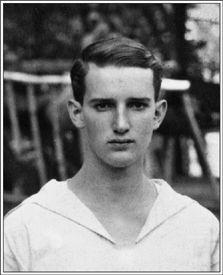

Jack Thayer

(photo credit 1.88)

Only moments after he came to the surface, Jack Thayer saw the forward funnel crash down about fifteen feet away from him. There was no sign of Milton Long, who had jumped from the rail about five seconds before him. Long had slid down the side of the hull while Thayer had jumped clear, saving his life by so doing. Jack looked back at the ship and saw it surrounded by a red glare. The stern was now standing at about a thirty-degree angle with light still blazing from its portholes. To Harold Bride, who was also in the water, it looked like a duck going down for a dive. The lights then blinked once and went out. Jack Thayer could hear the rumble and roar of what he thought must be the engines and boilers being torn from their beds. For Hugh Woolner in Collapsible D, the sound was like a thousand tons of rocks tumbling down a metal chute. To others in the lifeboats it sounded like explosions and many assumed that the boilers were blowing up.

But what they heard was actually the ship being wrenched apart. Unable to bear the strain, the ship broke in two just aft of the third funnel. An unnamed passenger later told a newspaper that he felt the ship shudder beneath his feet. “

It was as though someone had shouted ‘The ship is sinking!’ ” he recalled. Then he claimed that he, Archie Butt, and Clarence Moore jumped together into the sea. When the severed bow section began its plunge, Archibald Gracie found himself swirling downward within a whirlpool. He grabbed hold of the railing at the edge of the roof and held on, even as it pulled him down farther. Then it occurred to Gracie that he might be boiled alive by scalding water pouring up from the boilers. This notion caused him to let go of the railing and to kick upward as hard as he could. As he approached the surface, broken pieces of wood were ascending around him and he grabbed hold of a small plank. When his head broke the water Gracie saw a gray vapor over the sea and a mass of tangled wreckage. The

Titanic

was nowhere to be seen. He spied a wooden crate floating in some debris and paddled toward it. Just beyond it there was a capsized boat with men on its back and he swam over and pulled himself aboard.

The boat was overturned Collapsible B, and Jack Thayer was one of those already standing on it. A wave from the sinking bow section had washed him up against it, and from its back he had had a clear view of the

Titanic

’s last moments. “

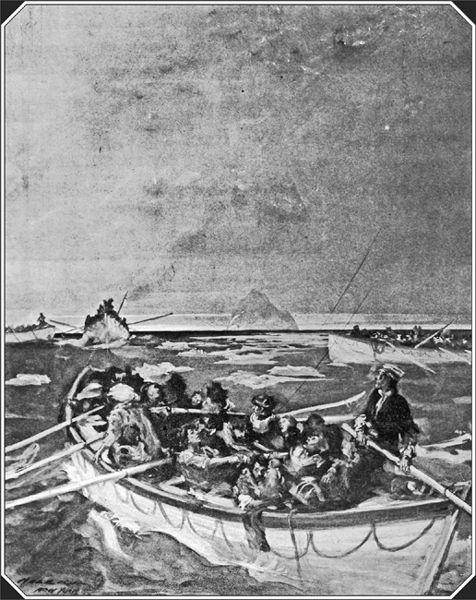

The stern then seemed to rise in the air,” he recalled, “and stopped at about an angle of sixty degrees. It seemed to hold there for a time and then with a hissing sound it shot right down out of sight with people jumping from the stern.” Norris Williams looked up from the water and saw the three propellers and rudder outlined against the sky over his head. He then watched as the stern pivoted before it went down with seemingly no suction and very little noise. Chief Baker Joughin also claimed there was no suction. Standing right at the stern railing by the flagpole, he said, he rode it down like an elevator and then paddled away without getting his hair wet.

“She’s gone,” Charles Lightoller heard those around him on the overturned boat murmur like a benediction. “

She’s gone, lads,” a crewman in Boat 3 echoed. “Row like hell or we’ll get the devil of a swell.” In the same boat an English businessman remembered that “

we raised our hats, bowed our heads and nobody spoke for some minutes.” In Boat 5, Third Officer Pitman looked at his watch and noted that it was 2:20 a.m. May Futrelle heard a Frenchwoman in her boat begin to wail but May herself didn’t cry, she just felt dead. In Collapsible C, Bruce Ismay couldn’t bear to watch and sat with his back turned to the sinking liner. Lucy Duff Gordon raised herself from a seasick stupor to see the black silhouette disappear in one downward rush.

Then, from across the water there came what Archibald Gracie called “

the most horrible sounds ever heard by mortal man.” To Hugh Woolner, it was “

the most fearful and bloodcurdling wail,” to René Harris it was “

a sound … as will haunt one all one’s life and into eternity.” Henry Harper called it “

a wild maniacal chorus” and concluded that many of the people must have gone mad as they felt the ship go down. To Edith Rosenbaum it sounded like cheering, and she recalled that a crewman in her boat encouraged them to cheer as well since it meant that all on board had gotten into lifeboats.

William Sloper was under no illusion as to the meaning of the wailing chorus. He remembered that whenever a light was lit in one of the lifeboats, it would be seen by the hundreds in the water and “

immediately their massed voices would rise and fall in a tremendous wailing crescendo which reverberated off into the starlit darkness of the silent night.” Lawrence Beesley thought that the cries carried with them “

every possible emotion of human fear, despair, agony, fierce resentment and blind anger, mingled—I am certain of this—with notes of infinite surprise, as though each one were saying, ‘How is it possible that this awful thing is happening to me? That I should be caught in this death trap?’ ” These “notes of infinite surprise” may have emanated most profoundly from the Gilded Age masters of the universe—Astor, Widener, Thayer, Guggenheim, Douglas, Moore, Hays, and others—who suddenly found themselves immersed in the freezing water. People used to die in shipwrecks, but this was the twentieth century. This sort of thing didn’t happen any longer, particularly not to people such as them.

Vigorous activity in cold water, it is now known, only intensifies the effects of hypothermia. Those who tried to swim without lifejackets out to boats were therefore likely among the first to perish. Archie Butt may have been one of them. An unnamed stoker who made it to Collapsible B later told a newspaper reporter that after he was helped aboard the overturned boat, “

a man in the uniform of an army officer crawled onto the raft, but he stiffened out at once and died. We threw him overboard to make room for a living man.” If this indeed is how Archie Butt died, then for him the end came fairly quickly. It seems sadly appropriate that a man who led such a “rushing life” ended it in one final burst of frenzied exertion. His body then disappeared beneath the black surface of the water, to descend in a slow drift to the ocean floor over two miles below.

For Frank Millet, death took its time, perhaps up to half an hour or longer, as he shivered under a brilliant canopy of stars, more beautiful than any he had seen in Byzantine mosaics or Venetian frescoes, impossible to ever capture in paint. For him, there may have moments for regret, reflection, or even insight before mental confusion fogged his consciousness and cardiac and respiratory failure set in. His body was recovered ten days later, standing upright in a cork lifejacket, his white tie visible beneath the collar of his black overcoat. His face was peaceful and there were no signs of struggle on his body.

To those in the lifeboats, it seemed as if the wails of the dying would never end. As time passed it became a monotone chant, what Helen Candee called a “

a heavy moan as of one being, from whom final agony forces a single sound.” It reminded Jack Thayer of the high-pitched hum of insects on a summer’s evening. René Harris thought of the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. Slowly, slowly the sound grew weaker, until it finally died away into the deathly stillness of the north Atlantic night.