Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (35 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

A

ppeal to the officer not to go back,” a woman in Boat 5 implored Steward Henry Etches. “Why should we lose all of our lives in a useless attempt to save those from the ship?” Others voiced their agreement, and as the protests mounted, Third Officer Pitman gave in and ordered that Boat 5 be turned away from the cries in the water. Similar scenes were enacted in many of the other lifeboats. Seaman Thomas Jones wanted Boat 8 to return, but when those at the oars refused, he announced, “

If any of us are saved, remember I wanted to go back. I would rather drown with them than leave them,”

The failure of all but two of the eighteen lifeboats to go to the aid of the dying remains another of the great “if only’s” of the

Titanic

story. Many of the boats were only half-full and, had they returned quickly, could have saved dozens of lives. In the Duff Gordons’ boat alone, there was room for twenty-eight more passengers. But in Boat 1, as in most of the lifeboats, the fear of being swamped by the panicked throng overruled all other instincts. “

It would have been sheer madness to have returned,” harrumphed Hugh Woolner in Collapsible D, only recently pulled into a boat himself.

To those who had left the

Titanic

in the early lifeboats, the cries in the water “

came as a thunderbolt, unexpected, inconceivable,” Lawrence Beesley later recalled. But Beesley also noted that “no-one in any of the boats … can have escaped the paralyzing shock of knowing that so short a distance away a tragedy, unbelievable in its magnitude, was being enacted.” Yet there were some in the lifeboats who simply could not believe that any cabin-class passengers had been left behind. “

I thought it was the steerage on rafts and that they were all hysterical,” claimed one first-class passenger. Mary Eloise Smith, an eighteen-year-old U.S. congressman’s daughter, thought that the cries were from “

seamen or possibly steerage who had overslept, it not occurring to me that my husband and my friends were not saved.” Yet twenty-four-year-old Lucian Smith, whom Mary Eloise had married only two months earlier, was indeed one of those not saved.

In Boat 4, most of the women realized that their husbands and sons could be among those struggling in the icy water, since they had waved good-bye to them only half an hour before. With Quartermaster Perkis at the tiller, Marian Thayer, Madeleine Astor, and Emily Ryerson and her younger daughter began rowing back determinedly, despite a few protests in their boat. Seven men were pulled into Boat 4, all of them crew or stewards. One passenger, the wife of a New York stockbroker, recognized her bedroom steward as he was hauled aboard. Two of the rescued men soon died, and several others lay moaning and delirious for most of the night.

In Boat 14, Fifth Officer Lowe was quite certain that it would be “

suicide” to row into the tumult and decided that he would wait until the crowd “thinned out” before returning. Lowe had taken charge of four other lifeboats and had ordered them tied together with Boat 14, about 150 yards away from the sinking liner. Daisy Minahan, the sister of the Wisconsin doctor who was one of those howling in the water, was less than impressed with the conduct of the young fifth officer. She claimed that Lowe had been making flippant remarks and swearing so much that he must have been drinking. When she and a few others begged him to transfer passengers and go back to rescue swimmers, he replied, “

You ought to be damn glad you are here and have got your own life.” When Lowe at last began moving passengers into the other boats, he yelled at Daisy, “Jump, God damn you, jump!” earning her permanent enmity.

But Lowe’s language was genteel compared to that of Quartermaster Hichens in Boat 6. When the horrifying cries came across the water, several passengers pleaded with Hichens to return, but the quartermaster refused, saying there would only be a lot of “stiffs” there. This upset a number of the women, but Arthur Peuchen could only say resignedly, “

It is no use arguing with that man. It is best not to discuss matters with him.” While the major sat glumly at his oar in a lifeboat less than half-full, most of his shipboard coterie—Harry Molson; Hudson and Bess Allison and their two-year-old daughter, Loraine; Mark Fortune and his nineteen-year-old son; the bachelor trio known as “the Three Musketeers”; Charles Hays, his son-in-law, and his twenty-two-year old assistant—all either drowned or slowly froze to death.

Fifth Officer Lowe

(photo credit 1.57)

Almost an hour had passed by the time Fifth Officer Lowe finally maneuvered Boat 14 into the wreckage. By then most of the wailing had subsided and only three or four men were rescued. One very large man, a first-class passenger named W. F. Hoyt, was pulled from the water bleeding from the nose and mouth and died shortly afterward. As they prepared to leave the scene, a floating door was suddenly spotted with what appeared to be a small Japanese man lashed to it. He looked frozen stiff and Lowe said, “

What’s the use? He’s dead, likely, and if he isn’t there’s others better worth saving than a Jap.” Eventually Lowe relented and the man was pulled into the boat, where several women began rubbing his chest, hands, and feet. Within seconds he opened his eyes, said a few words that no one understood, and then stood up and stretched. He soon took an oar and began rowing so diligently that Lowe had to admit that he was ashamed of what he’d said about “the little blighter.”

The rescued man was actually Chinese, one of eight Donaldson Line crewmen traveling in third class, four of whom had secreted themselves in the bow of Collapsible C.

In the dark, Lowe did not catch sight of the twenty or more people who had taken refuge on the partly submerged Collapsible A, Norris Williams among them. As he clung to the collapsible’s gunwale, Norris felt his fur coat weighing him down and quickly shrugged it off. He then made his way into the boat and found that he was able to stand in it even though the water was waist high. Someone near the bow organized a head count which soon faltered when it came to those who didn’t understand English. It was then proposed that they put up the collapsible’s canvas sides and try to bail out the boat. A passenger next to Norris became enthusiastic about this idea and asked the man ahead of him if he could borrow his bowler hat for bailing. The man refused, insisting, to Norris’s bemusement, that without his hat he would catch cold in the night air. But any hopes of bailing were abandoned when after much pulling it was discovered that the supports for the sides were broken and the canvas shredded. After this, it seemed as if only God could help them and when someone suggested a prayer, they stood together in the water with bowed heads. One of the most devout of the shivering supplicants was Rhoda Abbott, a seamstress and Salvation Army soldier who had jumped from the deck with her two teenaged sons but had lost them in the chaos near the plunging bow.

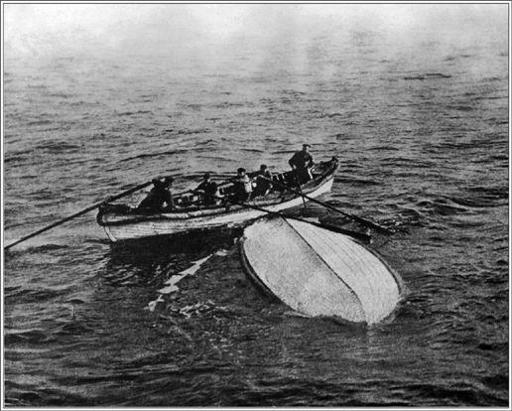

They prayed on the back of overturned Collapsible B as well. When the cries in the water died away, a crewman near the stern took a quick poll of the faiths of those around him and then led the group in the Lord’s Prayer. This heartened Archibald Gracie, who had been intimidated by the rough-looking men around him and had feared that he might receive “

short shrift” if they decided the boat needed to be lightened. Gracie had averted his eyes as swimmers were fended off with language that, in his words, “grated on my sensibilities.” As Fireman Harry Senior approached the collapsible he was hit over the head with an oar but went around to the other side and climbed on. Baker Charles Joughin was pushed off as he tried to board, but he, too, swam around the boat until he was recognized by one of the cooks, who reached out and clasped his arm. As Algernon Barkworth breaststroked toward the collapsible in Eton-trained style, someone shouted “

Look out, you will swamp us!” but Barkworth crawled aboard anyway, dripping like a wet sheepdog in his fur coat. The Yorkshire justice of the peace became the third first-class passenger, along with Gracie and Jack Thayer, among the roughly twenty-eight men on the overturned collapsible. Wireless operator Harold Bride was crowded in near the stern, next to Jack Thayer, with someone sitting on his feet. The Irish bagpiper Eugene Daly was one of approximately six third-class passengers who had also crawled aboard. Baker Joughin claimed that he simply hung on to the boat from the water, insulated by the alcohol he had drunk. The other men kneeled or crouched on the slippery ribs of the collapsible’s hull, and a few used boards and an oar to paddle away from the wreckage.

Approximately twenty-eight men found refuge on the back of overturned Collapsible B. It was later photographed by the crew of a ship from Halifax.

(photo credit 1.87)

Second Officer Lightoller soon took charge of the boat, much to Gracie’s relief. When the second officer learned that one of the Marconi men was on board, he asked Harold Bride what ships had replied to the distress calls. The junior wireless operator said that the

Carpathia

was the nearest one and that it should arrive within three hours. This raised everyone’s spirits and a crewman organized shouts of “Boat Ahoy! Boat Ahoy!” which reached peak volume when green flares were seen in the distance. These, however, were being lit by Fourth Officer Boxhall, who had taken a box of them into Boat 2. When the flares disappeared, Lightoller soon put a stop to the shouting.

In Boat 1, Cosmo Duff Gordon likewise told Henry Stengel to quit his incessant shouts of “Boat Ahoy.” Cosmo was worried about his wife, who was stretched out in the boat, seasick and shivering from the cold. Mabel Francatelli soon lay down next to “Madame,” as she called her employer, and from time to time, Lucy roused herself to reassure Cosmo that she was all right. She also tried occasionally to make light conversation and at one point teased Franks about the odd assortment of clothes she was wearing. “

Just fancy,” she said, “you actually left your beautiful nightdress behind you.” For Fireman Robert Pusey this proved to be too much. “Never mind about your nightdress, madam,” he retorted, “as long as you have got your life.” Another fireman joined in. “You people need not bother about losing your things for you can afford to buy new ones.” Seeing “Madame” stretched out in her fur coat and pink velvet designer mules made this all too apparent. “What about us?” the fireman continued. “We have lost all our kit and our pay stops from the moment the ship went down.” “Yes, that’s hard luck if you like,” replied Sir Cosmo. “But don’t worry, you will get another ship. At any rate I will give you a fiver towards getting a new kit.” He could not then have imagined how this small gesture of noblesse oblige would come to haunt him.

In Boat 6, Margaret Brown had doffed her sables to free her up for rowing. She had encouraged the other women to row as well, defying the quartermaster who railed at her from the stern. But Robert Hichens had chosen the wrong group of women to bully. In addition to the forceful Mrs. Brown, the plucky Mrs. Candee, and the voluble Berthe Mayné, there were two English suffragettes on board, Elsie Bowerman and her mother, Edith Chibnall. Both were active members of Sylvia Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, the most militant of Britain’s votes-for-women organizations. Edith was one of ten women who had accompanied Mrs. Pankhurst on a 1910 deputation to Parliament that had resulted in arrests after a scuffle with police. She had also donated a banner for a Hyde Park demonstration that read “

Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”