gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (12 page)

There is no way of knowing exactly when Göbekli Tepe gained its current name, although the chances are it replaced an earlier one meaning exactly the same thing, a process that might have been going on since the site’s final abandonment around 8000 BC. Evidence of this comes from the fact that the Kurdish name for the tell, which local people see even today as sacred, is Gire Navoke, which means “hill (

gire

) of the swollen belly (

navoke

),” with an emphasis on fertilization and pregnancy (Armenians, who formerly occupied eastern Turkey when it was part of Armenia Major, call Göbekli Tepe

Portasar,

meaning the “hill of the navel.” However, no historical evidence exists to show that this name was used prior to news of the site’s discovery in the year 2000.)

Possibly significant in this respect is that in the language of the Sumerians, who thrived on the Mesopotamia Plain from ca. 2900 BC to 1940 BC, the word for

placenta, ùš,

is more or less identical to that used for

blood

and

death

(

úš

), as well as the word for

base

or

foundation place

(

uš

), as in a place to set up the central pole for a tent.

5

Such a term might easily have applied to Göbekli Tepe, where the “pole” in question was represented by the enclosures’ twin central pillars.

In various indigenous cultures and civilizations the placenta was, and still is, considered a very sacred object, the disposal of which was of great importance not just to the future of the postnatal child, but also to the well-being of the family. Among the Acholi tribe of Uganda and the Sudan, for instance, placentas are buried in a spirit house made of stone at the center of a lineage shrine known as the

abila.

6

In Eastern Asia, Japan in particular, the placenta is buried with great dignity, often beneath a tree (another symbol of the sky pole). The site is thereafter venerated as a sacred place, with the placentas of emperors becoming the subject of annual festivals relating to the fecundity of the land and the prosperity of the people.

7

TEMPLE OF THE TWINS

Placentas, when featured in ancient myth and ritual, are often associated with the theme of twins, a matter that may well have some bearing on the presence of the twin pillars at the center of the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe. For example, among the Baganda tribe of Uganda the placenta and umbilical cord of the king are considered the source of his “twin” (

mulongo

), which is seen as the ghost or spirit of the placenta.

8

During the monarch’s life it is kept under constant watch in a specially built Temple of the Twin, and at the first sight of the lunar crescent each month it is brought into the king’s presence for a special ceremony. Once the ceremony is complete, the “twin” is “exposed in the doorway of the temple for the moon to shine upon it, and also anointed with butter.”

9

This exposure to the light of the moon takes place also on a second night, before the “twin” is hidden away for another month.

After the king’s death the “twin,” that is, the placenta and umbilical cord, is buried in the temple, along with his jaw, which thereafter functions as a point of communication with the dead monarch’s spirit, the relics being brought out on special occasions for oracular purposes.

10

At the same time a new Temple of the Twin is created for the next king, with the whole process being repeated (rather like the periodic construction of new enclosures at Göbekli Tepe).

Even in ancient Egypt the placenta formed the twin of the king, quite literally the seat of his soul double or alter ego. As in Baganda tradition, it was retained and carefully protected throughout his life and, following his death, was most probably buried in a special room

,

where it served as his

ka,

or double. To the ancient Egyptians the royal placenta was seen as a divinity in its own right, its cult attested as early as the late Predynastic period, ca. 3250–3050 BC.

11

More disturbingly, it is reported that in addition to placing placentas in the abila cult shrine, the Acholi tribe of Africa is said to have buried alive twins placed in jars at the same spot.

12

Whatever the reality of this macabre act, it further emphasizes the connection between twins and the placenta, which derives in the main from the primordial belief that when a child is born, his twin, symbolized by the placenta, is the one who dies, and thus becomes a spirit double of the living person. In this knowledge, it was considered that during pregnancy the womb

always

contains twins, each with his or her own soul and destiny.

The association between twins and the placenta is expressed also in the creation myth of the Dogon of Mali, in West Africa, where a double placenta forms inside the cosmic egg of Amma, the creator god, each one attached to a pair of twins.

13

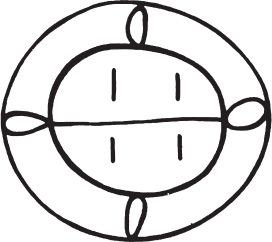

A Dogon pictogram showing the double placenta inside Amma’s egg closely resembles the elliptical appearance of the sanctuaries at Göbekli Tepe (see figure 5.1). More incredibly, vertical strokes drawn to represent the two sets of twins inside the egg eerily echo the placement and orientation of the twin pillars at the center of the enclosures.

TWIN PORTALS TO THE SKY WORLD

This information makes it highly likely that similar themes might have featured among the beliefs and practices of the Göbekli builders. If so, then the twin sets of pillars in the various enclosures at Göbekli Tepe could well signify human twins, either twins that exist in the womb during pregnancy or twins that are seen to have reentered some kind of symbolic womb in death (something that every entrant might have been seen to do when he or she entered the enclosures for shamanic purposes). Indeed, if the central pillars do symbolize twins, one representing the human soul, the other signifying the soul double, or ghost, then this practice might be related to a belief expressed by the Karo Batak peoples of Sumatra, which asserts that of the twin souls, a person’s

true

soul is that of the placenta, which was probably seen as “the seat of the transferable soul.”

14

In other words, in order to enter and navigate the spirit world, shamans or initiates had first to transfer the consciousness from their physical body to that of their twin; namely, the placenta soul. Thus the twin central pillars at Göbekli Tepe might have enforced a similar belief in the minds of entrants standing between them.

Figure 5.1. Dogon pictogram showing the two sets of twins inside the double placenta within Amma’s egg. Note how the vertical lines, representing the twins, eerily echo the twin central pillars in the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe.

Allied to this belief is the fact that the twin pillars at Göbekli Tepe most probably signified portals or gateways; that is, entranceways into the conceived axis mundi that would have transferred you instantly to the sky world (hollows in tree trunks are often seen to serve this function among shamanic-based societies). An instantaneous dimension shift of this sort would have been achieved through the use of one or more shamanic processes, including ecstatic dancing, ritual drumming, long-term sensory deprivation, and, of course, the ingestion of psychotropic or soporific substances (something suggested at Göbekli Tepe, as we have seen, through the profusion of snakes in its carved art and also by the presence of large basalt bowls used perhaps in the preparation of drugs and medicine). All of these methods would have enabled the mind to, quite literally, jump between worlds without any kind of delay involving regular space or time.

So where exactly was the sky world of the shaman during the age of Göbekli Tepe? In an attempt to answer this question, we must examine the deepest, most profound, cave art of Ice Age Europe.

6

WINDOW ON ANOTHER WORLD

I

f the hermetic axiom of “as above, so below” were to be applied to the construction of Göbekli Tepe in the tenth millennium BC, then it would suggest that ritual activity taking place within its enclosures was reflected in some manner in the heavens, and vice versa. Going beyond the imagined portal created by the twin pillars standing at the center of the structures is likely to have projected the shaman or initiate into some part of the night sky, but where exactly?

Some idea might be gleaned from the Ice Age cave artists of the late Paleolithic age. Although much of the beautiful imagery seen in the caves suggests a clear interface between the physical world and the perceived supernatural realms existing beyond human consciousness, certain painted panels are now thought to convey abstract celestial themes as well.

1

Three examples can be cited in this respect, and in each case the panels or friezes are positioned in the direction of the area of sky where the relevant stars were to be seen during the epoch in question.

THE LASCAUX SHAFT SCENE

The first example is the famous Shaft Scene from Lascaux Caves near Montignac in France’s Dordogne region. Located in a pit 16 feet (4.9 meters) deep, which could only be accessed using a rope (the remains of which have been found), the scene is composed of a set of images that have mystified paleontologists since the chance discovery of the cave complex by four teenagers in 1940.

From right to left, the painted fresco—which is approximately ten feet (three meters) across—shows a wounded bison, a birdman, a bird on a pole, and a rhinoceros (see figure 6.1 on p. 70, although the rhino is not shown here). Black loops drawn beneath the bison’s belly indicate the release of its entrails, perhaps by the barbed spear seen cutting across its body at an acute angle. Either that or it has been gored by the rhinoceros, which appears to be walking away from the scene. Facing the bison is a male human figure, who either has the head of a bird or wears a bird mask. He leans backward in a most awkward position and has an erect penis, a stance that could indicate he is a bird shaman experiencing an ecstatic trance state (the ingestion of psychotropic substances often causes male erection).

Confirming the significance of the figure’s avian features is the presence just below his feet of a bird on a pole, its head and beak resembling those of the birdman. Off to the left is the rhinoceros, whose role is debatable; he could have gored the bison, or he might simply be associated with the birdman’s blatant display of virility (rhino horn, being phallic in appearance, is valued in some cultures as an aphrodisiac). Next to the creature’s upraised tail are six black dots drawn in pairs, the meaning of which is unclear.

The panel’s awkward positioning at the bottom of a deep shaft, along with the fact that it shows the only human figure in the entire cave complex, indicates that it held some special significance to the Upper Paleolithic peoples who entered Lascaux and decorated its corridors and halls with a whole menagerie of Ice Age animals.

THE SUMMER TRIANGLE

Many scholars have attempted to understand Lascaux’s Shaft Scene, although no consensus regarding its meaning has ever been reached. However, in 2000 German scholar Dr. Michael Rappenglück of the University of Munich came up with a truly inspired interpretation of the painted panel. He argues that the entire scene is an abstract map of an area of sky featuring a group of three bright stars known collectively as the Summer Triangle, these being Altair in Aquila, Vega in Lyra, and Deneb, the brightest star in the constellation of Cygnus, the celestial bird or swan, known also as the Northern Cross.

2

At the time the Shaft Scene was created, ca. 16,500–15,000 BC, Deneb acted as the Pole Star, as it was the closest star to the celestial pole, the turning point of the heavens.