gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (47 page)

This absolute conviction in Mount Ararat’s role as the resting place of Noah’s ark has allowed it to be identified with all manner of legendary mountains thought to be located in this region. Any story relating to a nonspecific holy mountain in either Northern Mesopotamia or Armenia is automatically assumed to refer to Mount Ararat, simply because it is seen as the sole piece of land that God set aside to become the place of renewal of humanity following the receding of the waters at the time of the Flood. In the eyes of the Christian faith, no other holy mountain even comes close to the religious significance played by Mount Ararat in the emergence of humankind.

So much did Ararat become a sponge for myths and traditions attached to the mountains of Armenia that Abus Mons, or Mount Abus, modern Bingöl Mountain, the acknowledged source of the Euphrates and Araxes rivers, has been assumed to be Mount Ararat. This is despite the rather obvious fact that the sources of the Euphrates and Araxes do not take their rise on this mountain. The closest source of the Euphrates to Mount Ararat is 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, while the Araxes flows only through its foothills, having taken its course some 150 miles (240 kilometers) to the west on Bingöl Mountain, the true site of Abus Mons.

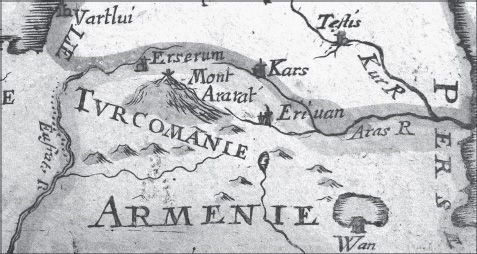

So absurd did this situation become that some maps of Armenia show a mountain in the approximate geographical position of Bingöl, from which emerge the Euphrates and Araxes rivers. However, instead of its being labeled Bingöl, or even Abus Mons, it is named Mount Ararat! (See figure 33.1 on p. 282.) This general confusion even led, as late as 1907, to the Araxes being cited as “rising in Mt. Ararat,”

5

when clearly its source is on Bingöl Mountain.

Figure 33.1. Section of a map of Armenia by French cartographer Alain Manesson Mallet (1630–1706), published in 1683. It misnames Bingöl Mountain, the clear source of the Euphrates and Araxes rivers, as Mount Ararat.

MOUNTAIN-LAND OF THE MINYAS

Bearing all this in mind, Baty’s assertion that the book of Enoch’s Mount Armon has been ably identified as Mount Ararat is completely groundless. Despite this, he was probably right to link this mythical location, where the Watchers swear their allegiance, with Armenia. In the book of Enoch, Armen, the root of the name Armenia, is the name of one of the rebel Watchers. He is said to have “taught the signs of the earth,”

6

this being a form of divination whereby the perturbations of the heavens are reflected also on earth, and vice versa, the rudiments, of course, of astrology.

The name of this Watcher derives most probably from another mythical figure named Armen, who is considered to be the legendary founder of Armenia. Quite possibly, the inclusion of Armen’s name in the book of Enoch relates to an Armenian location mentioned by classical writers under the name Armon,

7

or Armona,

8

a corruption of Har-minni, that is, Mount Minni (with variations such as Minyas and Minyadis).

9

In this form it is found in the Bible’s book of Jeremiah, which reads:

Lift ye up an ensign in the land,

Blow a trumpet among nations,

Sanctify against it nations,

Summon against it the kingdoms

of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz.

10

Here the Armenian kingdoms of Ararat and Ashkenaz are clearly separate to that of Minni, so where exactly was it to be found? English lexicographer William Smith (1813–1893) in his celebrated

Bible Dictionary,

published in 1884, states on the matter: “[In the Bible] MINNI only occurs in Jeremiah (51:27). It is probably identical with the district Minyas, in the upper valley of the Murad-su branch of the Euphrates.”

11

The Murad Şu, or Eastern Euphrates, flows westward through the Armenian Highlands and gradually turns south below the town of Varto before finally entering the plain of Mush. This places Minyas, or Minni, in the vicinity of the town of Varto, immediately south of the Bingöl massif, implying, if correct, that Har-minni, or Mount Minni, was most likely Bingöl Mountain itself.

HEAVENLY MOUNTAIN

German theologian Christian Abraham Wahl (1829–1901), whose biblical lexicons were published in the early nineteenth century, translated the name Har-Minni as meaning:

“Heavenly Mountain, the mountain whose top reaches to heaven, meaning Ararat; for

mino

in Zend, and

myno, myny

in Parsee, signify heaven, heavenly. And hence the ancients called the whole province of Ararat, Minyas.”

12

Once again a biblical scholar is beguiled by the magnetic draw of Mount Ararat, for as Jeremiah as well as Latin and Greek scholar William Smith make clear, the kingdom of Minni was

not

Ararat. Har-minni was thus another mountain, and although its exact location cannot be verified with absolute certainly, the fact that Ararat’s main rival Bingöl was once called Mingöl

13

seems a little beyond coincidence.

Since the Turkish root

bin,

“a thousand,” coupled with

göl,

“lake,” provides Bingöl’s normal translation of “a thousand lakes” or “a thousand springs,” it means that the root

min,

as in Mingöl, is either a corruption of

bin

or it relates to something else. Wahl’s second option seems more likely, as the name Bingöl Dağ is unattested before the writings of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689), a French diamond merchant and traveler who visited the region in the second half of the seventeenth century.

14

Perhaps as the German theologian Christian Wahl proposes, the name Har-minni (i.e., Mingöl) derives from a time when Armenia was under the control of the Persian Empire, which was between the sixth century BC and the time of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC, and again from AD 301 until the sixth century AD. Thus the word root

min

derives most probably from

mino,

which in the language of the Persian Zoroastrian holy books known as the Avesta means “heaven” or “heavenly.” It is a conclusion supported by the fact that in Persian

minú

means “azure heaven,”

15

while in Hindustani or Urdú, a language that includes many Persian words,

míná

means “heaven,”

16

while

mínú

means “paradise.”

17

Thus in Persian, Mingöl probably means something like “lake of heaven” or even “waters of paradise.”

18

All this tells us very firmly that the mountain named Armon, or Har-mini, upon which the rebel Watchers assembled and swore an oath of allegiance before descending on to the plain below, was located in Armenia, and not in the Levant, and is most probably Bingöl Mountain, the center of the Armenian obsidian trade during the age of Göbekli Tepe (see figure 33.2).

THE MOUNTAIN OF GOD

There is yet more evidence that the setting for the book of Enoch was the Armenian Highlands and not Mount Hermon in the Anti-Lebanon range. Polish-born Orientalist and scholar Edward Lipinski (b. 1930), who specializes in biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies, conducted a major investigation into the origins of the Mountain of God, the place where the Canaanite god El was said to dwell. Even in biblical times, this was deemed to be Mount Hermon, although Lipinksi found compelling evidence that it was originally located much farther north, in the kingdom of Armenia.

The first thing that the Belgium-based scholar observed was that the name of El’s abode was

g‘ r-ll,

the “mountain of the night.”

19

This is derived from the fact that its recesses were “toward the meeting place of the assembly” in the north where the sun never reaches, the Land of Darkness, as viewed from the perspective of the southerly placed Mesopotamian Plain, home of the Sumerians, Akkadians, and later Babylonians and Assyrians.

20

Lipinski was able to draw parallels between the name of El’s abode and the Sumerian place of God known as kur-suh-ha, “the dark mountain,” as well as “the mountain of darkness” in the Jewish Talmud, which contains teachings and lore relating to the contents of the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament.

21

The Talmud speaks also about a place called Gehenna, a kind of Jewish underworld, lying “behind the land of darkness,” somewhere in the Armenian Highlands.

22

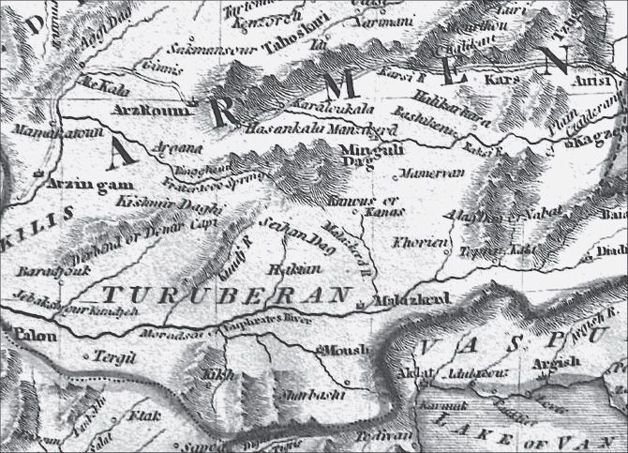

Figure 33.2. Section of a map of Armenia by Scottish cartographer John Tomson (ca. 1777–1840), published in Edinburgh in 1814. Here Bingöl Mountain is called Minguli Dağ, which derives from the Turkish for mountain (dağ ) and the Persian minjul, meaning “lake of heaven” or “waters of paradise.”

BENEATH THE POLE STAR

This was also where, Lipinski realized, Alexander the Great must have come seeking immortality in “the land of darkness,”

23

which was said to exist “in the north, beneath the Pole Star.”

24

According to the story, Alexander reached “‘the way of the Armenians’ country, where is the source of the Euphrates and of the Tigris,’ [here] he entered the wonderland, traversed the land of darkness, proceeded up to the country of the blessed ones, where ‘the sun does not shine,’ and, without knowing it, he reached the spring of life,”

25

located, as we have seen, on Bingöl Mountain. This story, Lipinski points out, was known as early as the third century BC, because the Greek philosopher and teacher Teles of Megara in ca. 240 BC says that humans want “as Alexander to become immortal.”

26

ENOCH IN PARADISE

All this was just a prelude for Lipinski’s investigation of the locations described in the book of Enoch, for he instantly recognized the same mythical locations cited here. At the beginning of the story, Enoch journeys to Paradise in the company of two angels, or Watchers, and comes “to a dark place and to a mountain, the point of whose summit reached to heaven.”

27

Here he saw “the mountains of the darkness of winter and the place whence the waters of the entire deep flow,” and “the mouths [i.e., sources] of all the rivers of the earth and the mouth of the deep.”

28

Additionally, after having “passed above a land of darkness,” Enoch “came next to the Paradise of righteousness,”

29

which Lipinski says, “has to be identified with the high mountain of God”

30

; that is, the aforementioned abode of El, who is a form of the Hebrew god Yahweh. This “Paradise of righteousness” is, of course, the Garden of Eden or terrestrial Paradise of the Genesis account, for here, we are told, “the throne of God was fixed where the Tree of Life was.”

31

TIGRIS TUNNEL

From this Lipsinki concluded that the entrance to the Land of Darkness, beyond which was the Mountain of God, was reached through “a gate of darkness, whose geographical origin is likely to be looked for in the tunnel at the source of the Western Tigris.”

32

This, of course, was the Reverend Marmaduke Carver’s western corner of his proposed terrestrial Paradise, its eastern corner being Lake Van, with its apex in the mountain range that included Abus Mons; that is, Bingöl Mountain.