gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (16 page)

As the Cross Bands glyph appears on these offering tables, usually either between the teeth of the monster or on the headdress worn by the were-jaguar, it is likely the Olmec also had some concept of the sun god being reborn from the Milky Way’s Great Rift, seen as the cavelike mouth of a hideous sky monster.

CLEAVING OPEN THE PORTALS

The Maya manufactured enormous ceremonial ax heads in jade that take the form of abstract were-jaguars, the lips on their human faces downturned in a peculiar and highly exaggerated manner (see figure 8.2). Across the top of the head, going from front to back, is a furrow or cleft, which has a deeply significant meaning, for on the were-jaguar’s breech cloth the Cross Bands glyph appears, like the Union Jack emblazoned on a belt buckle. According to the label accompanying the British Museum’s own were-jaguar hand ax:

The crossed bands glyph incised on the breech cloth signifies an entrance or opening. . . . These symbols (i.e., the glyph and the cleft on the top of the head) proclaim the axe’s magical power to cleave open the portals into the spirit world.

As that “spirit world” was almost certainly Xibalba, it confirms that the Cross Bands glyph symbolizes its “entrance or opening,” which, as we have seen, was marked by the constellation of Cygnus, the Northern Cross. Even the cleft is evidence of this connection, for the Great Rift is known also as the Great Cleft, as it appears to cleave the Milky Way in two, a symbolic act carried out in Mayan tradition by the jade ax in its celestial guise.

Figure 8.2. Left, Olmec altar at La Venta, in Mexico’s Tabasco state, showing a figure emerging from the cave-like mouth of the were-jaguar. Note the Cross Bands glyph between the creature’s fangs. Right, Mayan ax in jade fashioned into the likeness of the were-jaguar. Note the cross bands glyph on the belt buckle area of the breeches and the cleft on the top of the head.

THE DENEB PORTAL

Similar ideas regarding a spirit world existing beyond the opening to the Great Rift are held even today by a number of Native American tribes, whose star myths are thought to have a common origin among the Mississippi mound-building cultures, forming what is known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, which thrived ca. AD 1200–1650.

4

The most consistent story that emerges from their beliefs and practices tells of how in death the soul departs to the west, a journey that takes three to four days to complete. When finally it reaches the edge of the Earth’s disk, the soul waits for the right moment to make a leap of faith to enter the Milky Way, the so-called Path of Souls, via a star portal, knowing that the consequences of failing this difficult jump will mean being lost forever in the lower world.

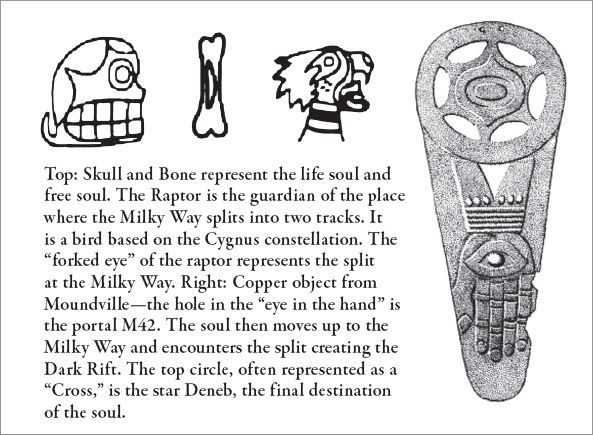

The portal is marked by a celestial hand, its fingers pointing downward and made up of stars belonging to the Orion constellation, the three belt stars marking the severed wrist. It is a symbol found again and again in the iconography of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex and dates back to the Hopewell mound builders of Ohio, who thrived some two thousand years ago.

The actual portal is the stellar object Messier 42, a small, fuzzy nebula located in Orion’s “sword.” Here the soul joins the Milky Way and travels south and then north until it reaches a fork on the path identified with the twin arms of the Great Rift. Its longer arm, the one bridging the two halves of the Milky Way, is envisioned as a log spanning a celestial river that the soul must cross to reach the sky world.

Yet before the soul can cross the log bridge it has to encounter its guardian, most usually a “forked-eye raptor,” a supernatural eagle known as the “Brain Smasher,” identified with the star Deneb. Only by receiving the right judgment can the soul avoid Brain Smasher and pass over the log and enter the afterlife. If the judgment is not favorable, the soul is forced to take the Great Rift’s shorter, severed arm, which leads only to oblivion. Clearly, the raptor is Cygnus in its role as the celestial bird, its forked eye the Milky Way’s Great Rift (see figure 8.3).

STORM DEMON WITH OPEN MOUTH

How exactly the Göbekli builders might have viewed the starry existence beyond the Great Rift is now lost. Yet some idea of their understanding of cosmic geography can be gleaned from the star lore recorded in cuneiform script by the astronomer-priests of the civilizations that thrived on the Mesopotamia Plain in what is today Iraq.

Figure 8.3. Native American symbols from artifacts found at mound sites. Note the raptor, which represents Cygnus, and the eye in the hand, representing Orion, above which is a circle that represents the bright star Deneb in Cygnus (after Greg Little).

Babylonian texts, which contain source material that goes back to the third millennium BC, catalogue dozens of stellar objects, either stars or asterisms, a few of which, such as the Scorpion (Scorpius), the Goat-headed Fish (Capricorn), and the Lion (Leo), are recognizable from their equivalents in the Greek zodiac. The stars of Cygnus would seem to have been combined with others from the neighboring constellation of Cepheus (located immediately above Deneb in astronomical terms) to create a huge griffinlike creature with the head and body of a panther (

nimru

in Akkadian) and the wings, back feet, and tail of an eagle. Its name was

MUL

UD.KA.DUH.A, which means “constellation (MUL) of the storm-demon with an open mouth,” and it was seen as the place of reception of dead souls.

5

With the head of the panther in Cygnus

6

and its tail in Cepheus (making it perfectly synchronized with the Milky Way), it becomes clear that in Babylonian star lore the entrance to the realm of the dead was through the mouth or gullet of

MUL

UD.KA.DUH.A, which corresponds to the opening of the Great Rift. This, of course, is similar to the Olmec and Mayan conception of the entrance to the underworld being through the mouth of a gruesome monster, either a jaguar or caiman. For this reason, it seems certain that the Babylonians, and presumably their forebears the Sumerians and Akkadians, saw the entrance to the netherworld, or realm of the dead, as synonymous with the Great Rift.

VENERATION OF THE POLE STAR

From the evidence presented here, it seems likely that the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of southeast Anatolia considered Deneb the visible marker for the opening into a sky world accessed via the Milky Way’s Great Rift. Why exactly this particular area of the sky became so important to the mind-set of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of southeast Anatolia lies in the fact that there was no Pole Star when Göbekli Tepe was constructed, ca. 9500–8000 BC. In other words, the celestial pole was not marked by any bright stellar object in the night sky. Thus it seems reasonable to suggest that the Göbekli builders adhered to much earlier Paleolithic traditions regarding the location of the sky world that reached back to a time when Deneb was Pole Star, ca. 16,500–14,500 BC. It was, of course, during this epoch that the Lascaux Shaft Scene was created by Paleolithic cave artists. This shows the bird on the pole, perhaps signifying the ascent of the bird-headed shaman (depicted next to it) into a sky world accessed through the celestial pole, marked at that time by Cygnus in the form of a bird.

SHIFTING POLE STARS

Is it really possible that the people of Göbekli Tepe followed a tradition that was more than five thousand years old? As already mentioned, the effects of precession caused the celestial pole to shift away from Cygnus around 13,000 BC. Thereafter it entered the constellation of Lyra, causing its bright star Vega to become Pole Star, ca. 13,000–11,000 BC. So why had the sky watchers of this age not switched their allegiance from Cygnus to Vega? The answer is that some Paleolithic cultures probably did start seeing Vega as the point of entry to the sky world. However, others almost certainly remained loyal to Cygnus, and Deneb in particular, simply because it synchronized with the start of the Milky Way’s Great Rift, which was already considered the rightful entrance to the sky world. Visually, the star Vega lies well away from both the Great Rift

and

the Milky Way, explaining why the star might not have attained the same significance as Deneb.

So not only did Vega lose its importance around 11,000 BC, but veneration of Deneb and the Great Rift as the true entrance to the sky world was almost certainly on the increase again, a situation that probably existed when the main enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were under construction in the tenth millennium BC. It thus makes sense that the builders of these monuments, the oldest known star temples anywhere in the world, chose to align them to the opening of the Great Rift, the most obvious point of entry into the sky world at that time.

Yet as we shall see next, the method by which the soul made its journey to and from the sky world was by using Cygnus’s most primordial totem, the celestial bird, which we find represented quite spectacularly in the carved art at Göbekli Tepe.

9

CULT OF THE VULTURE

A

t Çatal Höyük, the 9,500-year-old Neolithic city in southern central Anatolia, the dead were portrayed in art as headless matchstick men, often seen in the company of vultures. These are carrion or scavenger birds associated with the process of excarnation, the deliberate defleshing of human carcasses, which often took place on wooden mortuary towers, the remaining bones being afterward collected for what is known as a secondary, or disarticulated, burial.

Excarnation is certainly considered to have taken place during the Neolithic age and might even have occurred at Göbekli Tepe, according to Klaus Schmidt. He compares its large enclosures to the Towers of Silence that feature in the funerary practices of the religion known as Zoroastrianism,

1

which thrived in Iran, Armenia, and later India (under the name Parsism) until comparatively recent times. Here the dead were placed at the top of round stone towers, the Towers of Silence, away from a community. The vultures would swoop down and pick the carcasses clean, after which the remaining bones were allowed to calcine in the hot sun before being collected for final burial.

Although such practices are rare today, they do continue under the name sky burials among some remote Tibetan Buddhist communities in the Himalayas. Eyewitness reports show that first the vultures swoop down to devour the carcasses, then the ravens, hawks, and crows arrive to finish the job, almost as if this honor among birds might be the true origin of the term

pecking order

.

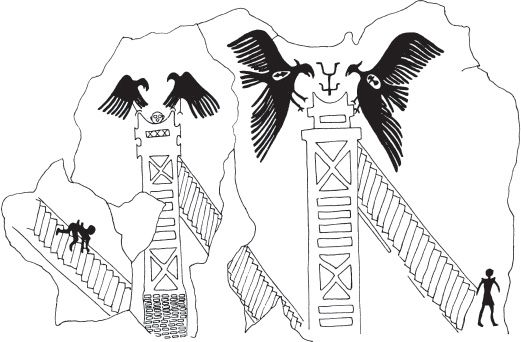

Excarnation almost certainly occurred at Çatal Höyük, where it is depicted on at least one painted fresco (see figure 9.1). This shows two wooden towers, accessed by a staircase, at the base of which are two figures, guardians perhaps of the charnel area. On top of the right-hand tower vultures attack a headless matchstick man, which is very likely an abstract symbol used to represent a dead body. The head was considered the seat of the soul, and because the soul has departed the body, it is portrayed as headless; that is, soulless. The missing head is seen in outline on top of the left-hand tower, where two vultures appear to be taking the head, or soul, under their wings.