gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (17 page)

Figure 9.1. Excarnation towers from a reconstructed panel found at the Neolithic city of Çatal Höyük, dating to 7500–5700 BC (after James Mellaart). Note the soul of the deceased depicted as a head, with its denuded body shown as a headless matchstick man.

PSYCHOPOMP

The painting is meant to convey the idea that, even though the human carcass might suffer the unsightly (although very efficient) act of excarnation, the spirits of the vultures accompany the soul into the afterlife. Each bird is thus acting as a

psychopomp,

an ancient Greek word meaning “soul carrier,” used to describe a supernatural being or creature whose role was to assist a newly deceased soul reach the next world.

British archaeologist James Mellaart recorded that all panels connected with death and rebirth at Çatal Höyük were located on either the north or east walls of cult shrines.

2

East is clearly the direction of rebirth, symbolized by the appearance of the sun each morning, leaving the north as the direction of the netherworld, the realm of darkness and the dead. Indeed, some of the most prominent vulture imagery featuring matchstick men at Çatal Höyük was placed on the north walls of cult shrines.

Not only is the north the only place where, in the Northern Hemisphere, the sun never reaches, it is also the direction of the Milky Way’s Great Rift, the stars of Cygnus, and, of course, the celestial pole. Was it in this direction, toward the perceived entrance to the sky world, that the vultures were thought to carry or accompany the soul into the afterlife?

Although Cygnus is most often represented in Eurasian star lore as a swan, evidence indicates it was once seen on the Euphrates as

Vultur cadens,

the “falling vulture,”

3

even though this is a title more commonly associated with the nearby constellation of Lyra.

GÖBEKLI’S VULTURE STONE

Representations of vultures were found among the ruins of the cult building at Nevalı Çori. Here Harald Hauptmann and his team uncovered a stone totem pole on which human heads and vultures are shown together, as well as a beautifully executed sculpture of a vulture that would not look out of place in a modern art gallery. Yet strangely this beautiful piece of art was being used as fill within the wall of the cult building, indicating that it belonged to an earlier phase of building activity, probably ca. 8500–8400 BC.

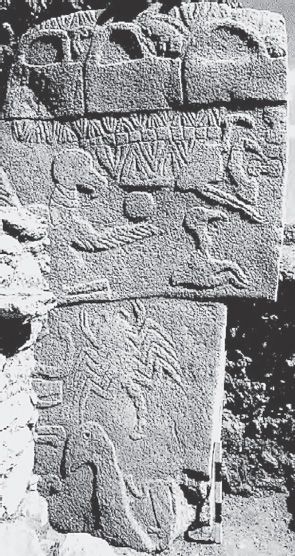

Vultures are also to be seen among the carved art at Göbekli Tepe, most obviously on Pillar 43. Located in the north-northwestern section of Enclosure D, it stands immediately west of the holed stone that would have allowed a person crouching between the twin pillars to observe the setting of Deneb during the epoch in question.

On Pillar 43’s western face are three vultures, one of which is a juvenile. Also visible is a scorpion and two long-necked wader birds—flamingos perhaps—and between them and the head of the adult vulture in the upper register is a line of small squares, abutted on each side by a series of V-shapes, possibly signifying the flow of water.

Other strange features are depicted at the top of the stone. Three rectangular forms appear in a line with linked loops that make them resemble handbags. Next to each is a small creature, which in order, from left to right, can be identified as a long-legged bird (a wader perhaps), a quadruped (seemingly a feline), and an amphibian (possibly a frog or toad). An interpretation of this scene is problematic, although the handbags, or “man bags,” as some people are calling them, are most likely animal pens or houses, situated on what could be the edge of a river, upon which is a trackway (the lines of squares) underneath which flows water (the accompanying V-shapes).

This, however, is not why Pillar 43 has been singled out as important. It is the vulture positioned at the end of the line of small squares that draws the eye (see figure 9.2 on p. 100). It stands up, with its wings articulated in a manner resembling human arms. It also has bent knees and bizarre flat feet, in the shape of oversized clowns’ shoes, indicating that this is very likely a shaman in the guise of a vulture or a bird spirit with anthropomorphic features. Similar vultures with articulated legs are depicted on the walls of shrines at Çatal Höyük, and these too are interpreted either as anthropomorphs or as shamans adorned in the manner of vultures.

4

HEAD LIKE A BALL

Just above the vulture’s right wing is a carved circle, like a ball or sun disk. Klaus Schmidt interprets this “ball” as a human head, and this is almost certainly what it is, for on the back of another vulture lower down the register is a headless, or soulless, figure, just like the examples found in association with the vultures and excarnation towers at Çatal Höyük. And we can be sure that this “ball”

does

represent a human head as similar balls are seen in the prehistoric rock art of the region, where their context makes it clear they represent human souls.

5

As Anatolian prehistoric rock art expert Muvaffak Uyanik explains:

Figure 9.2. Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone (Pillar 43). Note the scorpion on the shaft, the headless human figure with erect penis on the neck of the vulture-like bird at the base of the shaft, and the ball above the right wing of the vulture in the upper register.

In the Mesolithic age [i.e., in the epoch of the Göbekli builders], it was realized that man had a soul, apart from his body and, as it was accepted that the soul inhabited the head, only the skull of the human body was buried. We also know that the human soul was symbolized as a circle and that this symbol was later used, in a traditional manner, on tomb-stones without inscriptions.

6

So the headless figure represents not only the human skeleton but also a dead man whose soul has departed in the form of a ball-like head that is now under the charge of the vulture, which is itself arguably a bird spirit with human attributes, a were-vulture, if you like. Clearly, Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43—the Vulture Stone, as we shall call it—conveys in symbolic form the release of the soul into the care of the vulture in its role as psychopomp, or soul carrier, on its journey into the afterlife (Schmidt’s suggestion

7

that the vulture is playing with a human head as part of some macabre game is simply inadequate to explain what is going on here).

VULTURE WINGS

Evidence of vulture-related shamanism has been found also at other sites across the region. For instance, during the 1950s at an open-air settlement called Zawi Chemi Shanidar, which overlooks the Greater Zab River in the Zagros Mountains of northern Iraq, American archaeologists Ralph and Rose Solecki discovered the wings of seventeen large predatory birds, along with the skulls of at least fifteen goats and wild sheep.

Among the species of bird represented by the bones, many of them still articulated, were the bearded vulture (

Gypaetus barbatus

) and griffon vulture (

Gyps fulvus

), as well as various species of eagle. They were found positioned by the wall of a stone structure, which probably served a cultic function.

8

The excavators were in no doubt that the wings had been severed from the birds at the point of death and worn as part of a ritualistic costume.

9

In other words, shamans utilized these wings as “ritual paraphernalia”

10

in order to adopt the guise of the vulture in its role as a primary symbol of the cult of the dead.

The wings were radiocarbon dated to 8870 BC (+/- 300 years),

11

although modern forms of recalibration (due to recent reassessments of the amount of carbon-14 present in organic matter during former ages) means they probably date to the end of the Younger Dryas period, ca. 9600 BC

12

; that is, shortly before the construction of the large enclosures at Göbekli Tepe, which as the crow flies is about 280 miles (450 kilometers) west of Zawi Chemi Shanidar.

STAR MAP IN STONE

If Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone

does

show a human soul being accompanied into the afterlife by a psychopomp in the likeness of a vulture, then there has to be a chance that its rich imagery contains themes of a celestial nature. Scholars working in the field of archaeoastronomy have been quick to point out that the scorpion shown at the base of the shaft could signify the constellation Scorpius.

13

Certainly, in Babylonian astronomical texts such as those found on the Mul-Apin tablets, the stars of Scorpius are identified with a constellation named Scorpion (

MUL

GIR.TAB).

14

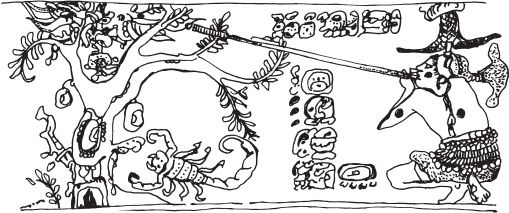

In the cosmological art of the Maya in Central America, a scorpion is often shown at the base of the world tree (see figure 9.3), a symbol interpreted by some scholars as the Milky Way standing erect on the horizon. This has led to the scorpion being identified with the constellation Scorpius, which lies immediately beneath the Milky Way’s Great Rift.

15

Thus it is conceivable that there existed a universal identification of the stars of Scorpius with the symbol of a scorpion that originated in the Paleolithic age, the reason it appears on Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone, carved ca. 9500–9000 BC.

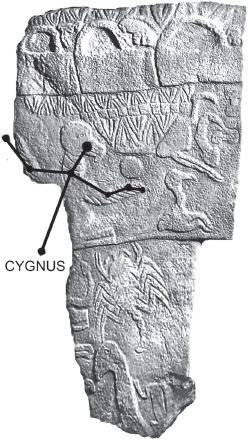

CYGNUS AS A VULTURE

If Pillar 43’s scorpion

does

represent the Scorpius constellation and is thus symbolizing the point of crossing between the ecliptic and the Milky Way’s Great Rift, then the vulture with articulated wings and clownlike feet at the top of the stone completes the cosmic picture. Its wings, head, neck, and body have a familiar ring to them, for they form a near perfect outline of the Cygnus constellation, with the vulture’s head in the position of Deneb and its outstretched wings matching those of its celestial counterpart as it appeared 11,500 years ago (see figure 9.4). This identification with Cygnus, first noted by Professor Vachagan Vahradyan of the Russian-Armenian (Slavonic) University,

16

is remarkable and unlikely to be coincidence.

Thus the abstract imagery on Pillar 43, with its headless matchstick man next to the scorpion, and the ball-like head above the left wing of the vulture, probably shows the transmigration of the soul from its terrestrial environment, signified by the stars of Scorpius at the base of the Milky Way’s Great Rift, to its final destination in the region of the Cygnus constellation at the top of the Great Rift.

Figure 9.3. Mayan cosmic tree, symbol of the Milky Way, with a scorpion by its base perhaps signifying the constellation Scorpius.

Figure 9.4. Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone (Pillar 43) with the Cygnus constellation overlaid.