gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (32 page)

ANCIENT MARINERS

All this is quite plausible, although there is now mounting evidence to suggest that the Solutreans also took to the high seas and ended up in North America, having navigated the southern limits of the sea ice that clogged large areas of the North Atlantic Ocean some twenty thousand years ago.

5

In North America, beyond the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached as far south as Missouri and the Ohio River Basin, the Solutrean hunters became the forerunners of the Clovis culture, producing laurel-leaf-shaped blades very similar to those manufactured in Western Europe. It was a tradition continued in the production of the exquisite Clovis points, manufactured using the pressure flaking technique by the Clovis people, who thrived in many parts of North America around the same time as the emergence of the Swiderian culture some thirteen thousand years ago. Yet unlike the Clovis culture that flourished for just five hundred to seven hundred years before disappearing during the Younger Dryas period, the Swiderians continued to thrive, creating all manner of post-Swiderian cultures, which, as we have seen, went on to occupy large areas of north and northeast Europe during Mesolithic times.

THE BRÜNN CONTROVERSY

Strengthening the connection between the Solutrean and Swiderian traditions still further is the fact that the two cultures might once have shared the same territories and the same physiognomy. It has long been known that a stone tool industry identical to that of the early Solutrean existed in Germany and the modern Czech Republic, and even further east in Hungary and Poland.

6

Anthropologists of the early twentieth century became convinced that the Solutreans derived not from Cro-Magnons but from the Brünn peoples, who emerged onto the scene in places such as Hungary and the Czech Republic around twenty-five thousand years ago, where they formed part of the much larger, and far older, Eastern Gravettian culture. This connection was no idle speculation either, for quite distinctive Solutrean tools and laurel-leaf blades were found in association with human remains of the Brünn type at two separate sites, one of them being PÅ™edmost in the Czech Republic, leading Princeton paleontologist and geologist Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935) to observe: “There is no question that the human remains [found at PÅ™edmost] belong to the middle Solutrean stage.”

7

It was a link that seemed confirmed with the discovery in the late nineteenth century of skulls similar to those of the Brünn type at Solutré, west of Mâcon in France’s Saône-et-Loire region,

8

which, as the name suggests, was the original “type-site” of the Solutrean tradition.

Yet when, in the second half of the twentieth century, typological thinking regarding the racial origins of humankind became unfashionable, if not downright distasteful, any proposed connections between the Brünn type and the Solutrean tradition were dropped. Not only did this leave the Solutreans without any definitive physical characteristics, but any notion that the Solutreans of Western Europe were related to the Solutreans of Central Europe was abandoned. Indeed, those of Central Europe were stripped completely of their Solutrean status and reclassified as a separate culture that evolved quite independently of the Solutreans of Western Europe.

Despite this awkward and somewhat strange reclassification process, it remains possible that the Solutrean tradition really is tied in with the sudden appearance in Central Europe of the Brünn population around twenty-five thousand years ago. Having said this, modern anthropological thinking has the Solutreans enter southwest Europe from Africa where, it has been suggested, they formed part of a Saharan culture known as the Aterian, which employed the use of strikingly similar toolmaking techniques. Yet equally likely is that the Solutreans and the human population of Central Europe categorized as the Brünn type came from the east, not the south.

Paleolithic stone tool expert Bruce Bradley, Ph.D., of the University of Exeter, and his colleagues have proposed that the Solutreans’ highly sophisticated stone technology originated among the peoples who occupied a region stretching from the cold forest steppes north and northeast of the Black Sea as far north as the central Russian Plain. Here between ca. 30,000 BC and 19,000 BC thrived an advanced culture known as the Kostenki-Streletskaya, which formed part of the much larger Eastern Gravettian tradition and produced stone tools and projectile points with close parallels to those manufactured by the Solutreans in both central and southwest Europe.

9

These Ice Age peoples of the Russian steppes and plain inhabited a series of settlement sites, including Kostenki, the culture’s principal type-site, on the west bank of the Don River, and Sungir on the Klyazma River. At this last site, located on the outskirts of the city of Vladimir, some 110 miles (177 kilometers) east-northeast of Moscow, three extraordinary human burials were uncovered in 1956. Each was adorned with thousands of ivory beads, which had been attached to tailored garments of immense sophistication. Radiocarbon evidence shows that the burials took place as early as 30,000 BC.

10

One of the skulls, Sungir 1,

11

bears similarities to some of the skulls found at the PÅ™edmost site in the Czech Republic, in particular an example known as PÅ™edmost 3. With its prominent brow ridge and pronounced jaw, it bears distinct characteristics of not only the Brünn population that entered Central Europe around twenty-five thousand years ago and perhaps kickstarted the Solutrean culture, but also the Neanderthal-human hybrid skulls found in Russia and Lithuania (see chapter 20), which might well have belonged to individuals stemming from the Swiderian culture. It is a supposition supported by the observations of one of the twentieth century’s greatest prehistorians, V. Gordon Childe. In his book

The Prehistory of European Society,

published in 1958, he writes:

In Western and Central Europe the “Solutrean” seems a brief episode that exercised no recognizable influence on subsequent developments. In Eastern Europe on the contrary Solutrean techniques were applied at times to the later East Gravettian (Kostienki) flint-work and survived locally even in the Mesolithic Swiderian industry.”

12

Childe recognized the close similarity between the “flint-work” of all three traditions and believed that the Swiderians and Solutreans derived their characteristic toolmaking capabilities from the Kostenki-Streletskaya culture of Central Russia. In other words, their true point of origin was not to be looked for in Central Europe, but much further east, on the Russian Plain, where highly advanced peoples, almost certainly related to the Brünn population, existed at places like Kostenki and Sungir as much as thirty-two thousand years ago.

Thus it is exciting to think that the legacy of these technologically advanced societies of the Upper Paleolithic might have had some influence on the events that led eventually to the construction of Göbekli Tepe during the tenth millennium BC. It is a surmise strengthened in the knowledge that one of the

only

known uses of carved stone blocks prior to the Neolithic age was among the Solutrean cave artists of southwest Europe.

SOLUTREAN STONE FRIEZES

In the collapsed rock shelter of Roc-de-Sers, located in France’s Poitou-Charente region, in the southwest of the country, archaeologists in the 1920s uncovered a series of huge limestone blocks, their front faces covered with deeply carved bas-reliefs of Ice Age animals and human forms. Ibexes, deer, bison, and boars are represented, as are reindeer and horses. All come together to form part of a multipiece rock frieze originally positioned in a semicircle on a natural ledge located at the rear of the shelter. In addition to this, lumps of manganese used to create a black pigment for painting were also found at Roc-de-Sers, suggesting that its elaborate rock frieze was originally painted in some manner. This incredible stone art, thought to be around nineteen thousand years old, has been firmly identified as belonging to the Solutrean occupation of the shelter, even though it would not look out of place among the gothic architecture of Chartres Cathedral or Notre Dame de Paris (see figure 21.2).

Two more carved stone blocks were found at the Fourneau du Diable rock shelter in France’s Dordogne region, and these have also been identified as belonging to the Solutrean tradition. In addition to this, archaeologists found within the Solutrean layers in the Cueva del Parpalló rock shelter, situated on the slopes of Montdúber Mountain in Valencia, Spain, literally thousands of painted stone slabs.

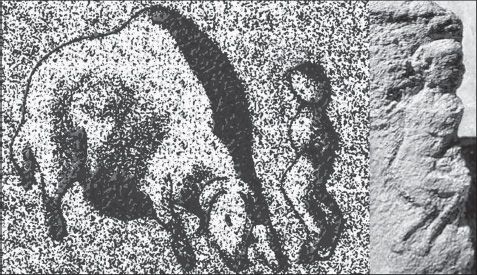

Figure 21.2. Carved stone block from the Roc-de-Sers shelter in France’s Poitou-Charente region, showing a horse (on the left), and bull, its head recarved as a boar. Solutrean period, ca. 17,000 BC.

Although direct evidence of ritual activity, and even burials, is sadly lacking when it comes to the Solutreans, it is proposed that the “placement of engraved blocks at some sites, the accumulation of painted slabs at Parpalló, and even the abundance of elaborate worked stone points at a number of sites all reflect some type of ceremonial or ritual activities.”

13

In other words, the unique rock friezes found at Solutrean sites might well have had a magico-religious function similar to that of the decorated T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe.

PURSUED BY A BULL

One block is of particular significance at Roc-de-Sers. It shows a human figure, a male it seems, with a pudding-basin haircut and slightly bent legs (see figure 21.3). He appears to be either baiting or escaping from a pursuer in the form of a huge musk ox, its three-dimensional head lowered in readiness to charge. The clear relationship between this human form and an aggressive bovine has led to comparisons with the Shaft Scene in the Lascaux Caves. This, as we shall recall, shows a reclining birdman being confronted by a wounded bison.

Figure 21.3. Left, drawing showing a musk ox pursuing a human figure from the rock frieze found at Roc-de-Sers. Right, the aforementioned human figure as seen on the rock frieze. Solutrean period, ca. 17,000 BC.

Yet the connection with Lascaux goes deeper, for stylistic and dating evidence indicates that its famous Shaft Scene was executed not by Magdalenian cave artists, as most prehistorians assume, but by Solutreans who entered the well shaft as early as 16,500 BC.

14

SOLUTREAN BIRD CULT?

More incredibly, the only other human figure depicted among the stone blocks forming the frieze at Roc-de-Sers appears to be wearing a bird mask. It is carved on the very same block as the aforementioned musk ox and figure with pudding-basin haircut. This mask-wearing figure, which also has slightly bent legs, might well have an erect phallus, like the birdman in Lascaux’s Shaft Scene (see figure 21.4 on p. 186 to judge for yourself). Clearly, bird totemism, perhaps involving ecstatic states and mask-wearing rituals, could have been important to the Solutrean peoples of southwest Europe.

This conclusion is strengthened by the presence in various caves decorated during the Solutrean period of a strange abstract symbol known as the aviform. This is a long, thick, horizontal line, with downward-turned lines at each end and a vertical extension, either up or down, at its center.

Aviform

means “birdlike,” and there is no denying the birdlike appearance of these devices, which are found so often that they might well be a sign of recognition among a particular Solutrean grouping or subculture. Yet if these

are

birds, then their downturned outer wings suggest they have adopted a gliding position, usually seen when birds are kept aloft by thermals generated by columns of warm air (see figure 21.5). It is a method of flight used particularly by raptors, vultures, seagulls, and storks, as well as by smaller birds such as swallows and swifts. Thus the aviform could represent either astral flight or the soul of the shaman in the form of a bird.