gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (36 page)

So how then did a river named Gail, or wolf, come to be called Peri Şu by the region’s Kurdish inhabitants, and did this information have any obvious bearing on Bingöl’s long association with obsidian?

Kurdish folklore asserts that the mountains and valleys around the Peri Şu were once the haunt of the Peri, the offspring of fallen angels in Persian myth and legend. They are said to have been tall, strong, beautiful, “super human beings that could cohabit with mortal kind.”

*14

19

It was even believed that certain communities of Kurds, particularly those that included pale-looking females, were the descendants of Peri that had mated with mortal kind

.

20

According to a Kurd who was born and raised in a rural village close to the obsidian route between Bingöl and Diyarbakır, the Peri were linked to the local obsidian trade in stories once told by the most elderly members of the community.

21

How exactly, unfortunately, has now been lost.

Yet the fact that the Peri Şu, or Gail River, rises on Bingöl Mountain links these various traditions with mythical individuals who might well have been identified not only with the Peri of Kurdish folklore, but also with both the wolf and obsidian. It is even possible that we have here a dim recollection of the arrival in the region of Swiderian peoples from central and eastern Europe.

If all this is correct, then how would these European hunters, whose totem animals included the wolf and reindeer, convince the indigenous peoples of southeast Anatolia to embark on the construction of monumental architecture unlike anything ever seen before in the ancient world? It is time now to examine just how exactly the hunting magic of the Swiderians might have gone on to influence the strange world that emerged at Göbekli Tepe in the aftermath of the Younger Dryas mini ice age ca. 9600–9500 BC.

25

SAVIORS OF THE WORLD

P

olish anthropologist Maria Czaplicka (1884–1921) made a study of the Koryak reindeer herders of Siberia’s Kamchatka Krai, which is in the extreme northeast of Russia (a krai is a federal subject, or political division, of Russia). One ceremony she recorded involved the slaughter of a wolf and then the killing of a reindeer. The latter was decapitated, and its head and body placed alongside that of the slain wolf on a raised platform. The rite was a sacrifice to Gicholan, “The-One-on-High,” the Koryak supreme being, upon whom they called to prevent the wolf from attacking the herd. A feast was afterward prepared and eaten, at which “the wolf is fed”; that is, its spirit was appeased. Czaplicka goes on:

The night is spent without sleep, in beating the drum, and dancing to entertain the wolf, lest his relatives come and take revenge. Beating the drum and addressing themselves to the wolf, the people say, “Be well! (Nimeleu jatvanvota!),” and addressing The-One-on-High, they say, “Be good, do not make the wolf bad!”

1

Yet in answer as to whether this ritual was done to ward off wolves, the Koryak insisted that the animal was not dangerous in its visible state, especially as the northern wolf generally avoids human contact. Czaplicka said it was dangerous only in its “invisible, anthropomorphic form”; that is, as a werewolf, a half-human, half-wolf. With this in mind, she noted that in Koryak tradition:

The wolf is a rich reindeer-owner and the powerful master of the tundra . . . [and] avenges [himself] particularly on those that hunt [wolves]. The Reindeer Koryak, who have special reason to fear the wolf on account of their herds, regard this animal as a powerful shaman and an evil spirit.

2

Thus for the Koryak the wolf was both a “powerful shaman and an evil spirit,” a force to be reckoned with on a supernatural level.

WOLF-STICK FESTIVAL

In another ritual celebration practiced by the Koryak, called the Wolf-stick Festival (Elhogi Çayönüin), a wolf was killed, skinned, and decapitated. Moving across to a hearth the participants would then place a pointed stick in the ground, to which they would tie an arrow. Alternatively, the arrow was driven into the earth, with its point sticking upward. A man would then adorn himself in the wolf ’s skin and walk in circles around the hearth to the beat of a drum played by someone standing nearby. When questioned as to why they conducted this ritual, the Koryak would simply shrug their shoulders and say: “Our forefathers did [it] this way.”

3

THE SHAMAN’S POLE

Czaplicka was mystified as to why during the Wolf-stick Festival the Koryak stuck a stick in the ground with an arrow tied to it or used an arrow instead. Yet an explanation is actually quite simple, for it cannot be coincidence that shamanistic practices in Siberia, and many other parts of the world, involve the erection of a stick or pole that represents the axis mundi, the axis of the earth.

The shaman’s pole, which can even be the central support of a skin-covered tent, then becomes the means by which the shaman gains entry to the sky world, either by ascending it in astral form and/or by actually

climbing

the pole, like some weird circus act in a big top. As Czaplicka herself pointed out in connection with the cosmological views of the Chukchi, a Siberian tribe whose territories border those of the Koryak:

A hole, under the pole-star, forms a passage from one world to the other, and through this hole shamans and spirits pass from one to another of the worlds.

4

Such beliefs and practices are likely to have existed in Paleolithic times, and if this is correct, then there is no reason they cannot have survived into the modern era in remote parts of Siberia. The existence of rituals such as the Wolf-stick Festival of the Koryak demonstrates the absolute necessity of a tribal group in countering the malefic intentions of their enemies; not here, but in the spirit world, where they can be confronted head-on by the shaman, who might well take on the mantle of the wolf to deal directly with a feared and respected rival or enemy.

OCCULT BATTLE

These are psychological processes most assuredly, but it is as well to recall that during the Second World War British witches and occultists—most famously Dion Fortune (1890–1946), who lived at Glastonbury at the time—became entangled in what they saw as a magical battle of life and death in order to counteract the threat of Nazi Germany to British freedom. Those taking part conducted regular rituals, meditations, and psychic battles to ensure an Allied victory. These individuals believed that what they were doing was very real indeed, and no amount of skepticism would have convinced them otherwise. It is extremely likely that something similar was going on in the aftermath of the Younger Dryas Boundary impact event involving European reindeer hunters and wolf shamans countering the baleful influence of the cosmic trickster in the form of the wolf or fox.

Did the Paleolithic peoples eventually claim victory over the forces of the sky wolf, or sky fox, in a manner echoed in the outcome of the Scandinavian account of Ragnarök, the Twilight of the Gods? Did their claims, handed down from one generation to the next, have any bearing on the story of how the god Tíw, or Tyr, sacrificed his right arm in order that the Fenris Wolf might be bound forever, saving the lives not just of the remaining Æsir, or Asa gods, but also the fledgling strains of humanity? Remember, this was seen as a compassionate act of self-sacrifice that gained Tíw the epithet “leavings of the wolf.”

Not only was Tíw considered a divine protector of the North Star or celestial pole, but his symbol, the T-rune Tiwaz, is the outline of an arrow, and, as we saw in chapter 16, a representation of the

“

vault of heaven held up by the universal column,”

5

as well as the Irminsul, or “world-column of the Saxons that terminates in the pole star.”

6

The symbolism is thus the same as the arrow and pole used in the Koryak Wolf-stick Festival, with all of it being done to counter the trickster wolf and ensure the future stability of the world.

STRANGE CUSTOMS OF THE SÁMI

Further evidence of this surmise comes from the Sámi, the shamanic-based tribal culture and, until fairly recently, reindeer herders who have existed in Finland, northern Scandinavia, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia since Mesolithic times (see figure 25.1 on p. 211). According to noted Swedish ethnologist Uno Harva (1882–1949), the Sámi practiced a “strange custom” whereby they made sacrifices to a sky god “so the sky or the world would not fall down.”

7

For this they erected a forked tree, or tall pole, on the top of which they placed an iron nail, symbolizing the “world pillar,” next to which an altar was created so that the god “could support and keep the world, that it would not grow old and fall from its former position.”

8

Harva compared the Sámi’s sky pole with the Irminsul of the Saxons, linking it back to the Tiwaz rune, which was known both to the Scandinavians and the Germanic peoples.

9

According to an eighteenth-century missionary named Jens Kildal (1683–1767), the Norwegian Sámi believed in a high god called Maylmen Radien, in whose honor a world pillar or axis mundi called Maylmen Stytto was erected and “smeared with the blood of a sacrificial reindeer oxen.”

10

Here we have clear evidence of shamanic rituals taking place among the Sámi to preserve the stability of the sky pole, or world pillar (the Maylmen Stytto was thought to connect with the celestial pole). This was done in order that it might “not grow old and fall from its former position” or that “the sky or the world would not fall down”; that is, so that it would not be destroyed, either through neglect or, might we say, through the intrusion of some kind of supernatural agency, such as a sky wolf or sky fox

*15

(the reindeer, wolf, and fox are key animals depicted on Sámi shaman drums, alongside a central cross variously described as the world tree [Saiva Moura], the world pillar [Maylmen Stytto], and even the Cross of Christ).

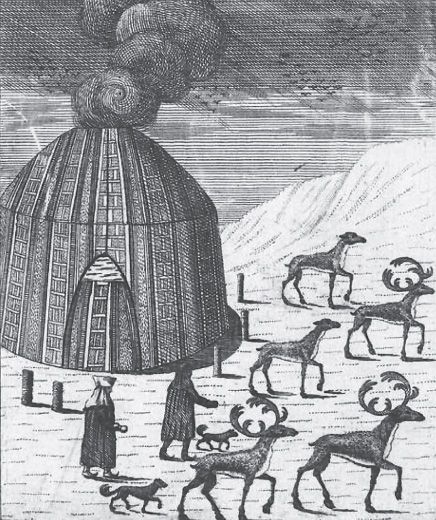

Figure 25.1. Antique line drawing showing Sámi reindeer herders.

FINNO-UGRIC ORIGINS

The significant point about the Sámi is that they belong to an ethnic group that forms part of the Finno-Ugric language family. Not only is there a relationship between the Finno-Ugric language and both Armenian and Hungarian, but there is evidence also that the Sámi inherited traditions from a post-Swiderian culture responsible for the spread of the Finno-Ugric group of languages into Scandinavia, Estonia, and Finland.

11

Thus there exists some small chance that the beliefs and practices of the Sámi owe some debt to those practiced by the Swiderian reindeer hunters, including, we can only assume, shamanic rites to preserve the stability of the sky pole so that the world does not come to an end.

With all this in mind, can we go on to imagine Swiderian groups reaching the Armenian Highlands in the wake of the catastrophic events that would appear to have affected the world in the eleventh millennium BC and claiming that their hunting magic and their understanding of the sky wolf or sky fox, had, quite literally, brought humankind back from the brink of destruction? Did they offer to reveal how the hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia could themselves stabilize the world pillar and counter the baleful influence of the cosmic trickster so that “the sky or the world would not fall down”?

Such speculation might seem crazy, but we have to imagine ourselves in the position of the hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia at the end of the Paleolithic age and attempt to understand why they might have embarked on mammoth building projects such as Göbekli Tepe. If the large enclosures, built ca. 9500–8900 BC, are not the end product of hundreds, if not thousands, of years of gradual evolution, then it is possible they were inspired not only by the fear of a further cataclysm taking place but also by new ideas carried into the region by outsiders. As we have seen, by far the best candidates for this role are the Swiderians, who would seem to have been carrying traditions inherited from their likely forebears, the Solutreans and Kestenki-Streletskaya culture of the Russian Plain, in particular a knowledge of cosmic geography and shamanistic practices involving the concept of the sky pole used to reach a sky world existing in the area of the Cygnus region.

FOX, NOT WOLF?

One question remains before we can move on: If Fenris is a wolf, and the European reindeer hunters arrived in Anatolia claiming an association with this animal, why don’t we see the wolf depicted more at Göbekli Tepe? The answer is that the wolf

is

represented among the carved art at Göbekli Tepe. It is very likely the identity of at least three “predators” or “quadrupeds” represented by 3-D statues found at the site, which are today on display at the Şanlıurfa archaeological museum. That said, it is the fox that predominates among the carved art seen in the enclosures, especially on the inner faces of the central pillars. It was this realization, along with the large number of faunal remains belonging to the red fox found at the site, that prompted archaeozoologist Joris Peters and Klaus Schmidt to conclude that “a specific worship of foxes may be reflected here.”

12