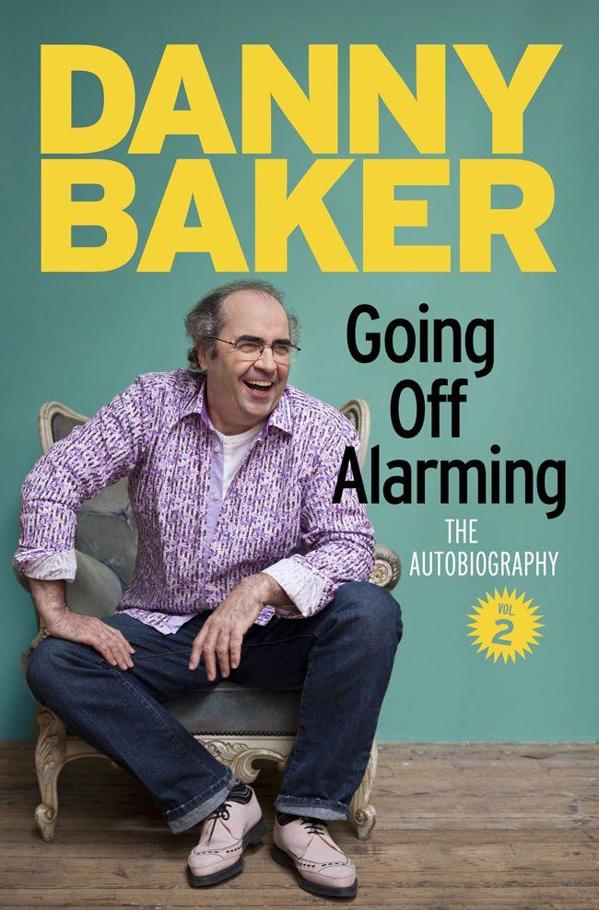

Going Off Alarming: The Autobiography: Vol 2

Read Going Off Alarming: The Autobiography: Vol 2 Online

Authors: Danny Baker

Going Off Alarming

A MEMOIR

WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON

LONDON

The true propellers and turbos amid all these words are Bonnie and Sonny. This is from your dad, kids. Mancie, you’ll just have to sit up on your cloud and be born in the next one, OK?

Contents

Teas, Light Refreshments And Minerals

Does This Kind Of Life Look Interesting To You?

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

First photo of me. I’m on the right, playing with Stephen Micalef by the rubbish chute in the flats.

Debnams Road, where I lived until I was twenty. Ours was the first door along.

Spud typically enjoying both life and the Courvoisier. My brother’s picture is beside him.

Outside the caravan shortly before shattering my legs in the ill-advised Dr Syn fiasco.

Michael Aspel and me on

The Six O’Clock Show

. Or possibly

Waiting for Godot

.

Wendy holding Bonnie in Deptford Park. Our house is roughly centre in the row behind.

I forced Sonny out to make his own way in the world when he was three. I presume he’s doing OK.

Twizzle again. We never suspected he was mad.

The only picture I have of my time in panto. Here I am appealing for any loose change.

The cover of the programme from The Great Dick Whittington Scam.

Meeting my absolute hero Anthony Newley while dressed as my own five-year-old son.

My father-in-law Jim possibly recalling the night a molten lampshade scarred him for life.

Thumb chums. Sonny in our front room with Paul Gascoigne. Paul is on the right.

F

or what it’s worth I would like to dedicate this book to my brother Mickey. If there’s any detectable chronology at all in these volumes then Mickey died just after the last one finished and this one begins. Following a fellow docker’s enormously boozy leaving do, he went home to bed and simply didn’t wake up again. I’ve wrestled with how to place his sudden passing into the cavalcade of events that gather in these pages, but no matter how I approach it the problem always remains the same; I am just no good at morbid reportage. All the stories told here are true and all, I hope, contain something fresh, surprising and entertaining for the reader. To simply write out the tragic impact of Michael’s death on the people around him seems to me, in a literary sense, obvious and strangely banal. In my own reading tastes I have never had the slightest interest in poking about in other people’s bad news, whether in book, magazine or broadcast, and this is possibly why I have no idea how to serve such stuff up as a cracking good chapter. I grant that some may see the reticence to dwell on the dark months immediately following Mick dying as the psychological key to everything else contained here, but I’m afraid it really isn’t. There is no long-subsumed secret sorrow here from which to unburden myself. To put it simply: my brother died. How do you think it fucking felt? There are more than enough misery memoirs out there if people want to bizarrely nose about in the grief of others and, as I say, I am genuinely not armed with whatever heart-wrenching tools are required to guide an audience through the universal details or even how to make them interesting. I’m absolutely certain when it comes to publicizing this volume, interviewers will narrow their eyes and say,

‘You

seem to skip over

your brother’s death. Why is

that?’

as though this would have been the really interesting part of my tale. The media is funny like that. So when that happens I will offer them a phrase that my mum would say whenever somebody started going on about how terrible life is and, for my money, it’s something you really don’t hear often enough these days. Once anyone began edging toward what we now label

‘confessional’,

Mum would lean forward and touch their arm.

‘Ooh

love,’

she’d coo, not a little alarmed at being trapped by all the drawn-out gloom,

‘We’ve

all got our problems, mate, and besides

. . .

it’s none of our business, is

it?’

So here’s to you, Mickey, his wife Jane and daughter Alex. Family.

T

hey say you never hear the shot that kills you, so at least I knew I wasn’t going to die.

I had definitely heard the slug as it left the pistol, a ballistic snap identical to the spit of a log fire, and besides, the sharp pain and fast-blossoming bloodstain were located on the outside of my right knee so unless my assailant had tipped his bullets with cyanide, my life was probably not hanging in the balance. However, shot I most certainly had been and I now doubled over to grasp my punctured leg, turning about in small alarmed hops while emitting shocked choking sounds like a dog trying to sick up a feather. None of my friends appeared to have noticed the gunfire and continued to amble along Jamaica Road in their shared drunken buzz. We had been having a

‘late

one’

in any of the various Bermondsey pubs that took a relaxed attitude to the legal drinking hours and were now meandering back through the borough, here and there losing a few from our original strength of fourteen as we passed the streets and estates where most of us still lived with our parents. There was little traffic this Sunday night and so I had got a pretty good look at the passing bottle-green Rover from which someone had just held a pistol out of the rear window and fired.

‘I

been shot! Someone just fucking shot

me!’

I bleated after my group while actually trying to put most of the alarm I felt into my facial expression rather than the pitch of the message – after all, it was nearly 1 a.m. and we were passing some flats where dozens of people we knew were fast asleep. Even in such a crisis I was aware that if any of them saw my dad the next day and said,

‘Here

, your Danny was pissed and causing a row outside our block last

night,’

it would really put the tin hat on affairs. So it was more in the style of a strangulated stage whisper that I drew attention to having just become a victim of what we now call a drive-by.

John Hannon reacted first.

‘Shot

? What y’talking about,

shot?’

he asked almost wearily, as if I’d asked him to help me find a shirt button.

‘Shot!’

I cried, stage whisper rising toward boiling kettle.

‘Some

fucker in a car just got me in the

leg!’

John turned to the rest of the chaps. With a chuckle in his voice he jerked a thumb toward my buckled pose and chortled,

‘Baker’s

just got

shot!’

And everyone began laughing.

Crowding around me under the street lighting they saw that the

‘bullet’,

an inch-long chrome slug, had buried itself into the top of my knee right up to the yellow flights that adorned its base. Unconcerned with my pain, they seemed more intrigued as to who might have done it. The car I had identified to them was now well down the road and as it receded in the gloom it gave no clue as to its occupants. After a few moments dwelling on possible local suspects it was agreed – though not by me – that this was merely the work of a little mob from over East London,

‘just

fucking about, having a

laugh.’

The Rotherhithe Tunnel under the Thames lies at the end of Jamaica Road towards which the car sped and this would logically take them back to their own part of town. Case closed.

Forming my index, middle finger and thumb into a claw, I set about pulling the slim bullet out. In silence, my friends gathered about me to take in the gore. This was a mistake. For in turning all my attention to the injury I had stupidly dropped my guard and carelessly become the softest of targets. And it was literally the softest of targets that was about to receive a slapstick second blast. Believing the immediate threat to be over, none of us had double-checked that the mystery car had actually driven into the Rotherhithe Tunnel. It hadn’t. On arriving at the roundabout at the subway’s entrance it had in fact turned around and was coming back up towards us on the other side of the road. I certainly couldn’t see this because I was facing away from the road. Bent over. From my pistol

packin’

tormentor’s vantage point, I was now

presenting the fullest and most irresistible of targets. I fancy I was waving my rear end around a little, thus making the bullseye even more alluring.

Crack.

The dirty double-dip bastards shot me right up the arse. This time I not only heard the report, I was forced to process their wild whoops of glee as the car sped off once again – in the direction of Tower Bridge. I of course snapped violently upright as though I were spring-loaded, both hands grasping the under-fire cheeks, and turning the phrase,

‘Fucking

hell, they’ve just shot me up the

arse!’

into one long strangulated word. Now, if you thought my

colleagues’

reaction after the first attack was possibly callous, I’m sure you must concede this occasion deserved nothing short of roars. Shocked as I was, I knew even at the moment of impact that being shot up the arse was, comically, a classic. By morning the sketch would be all over South-East London with pensioners, priests and close family members having to stuff handkerchiefs into their mouths in failed efforts to stifle outright guffaws. The only thing that might temper the hilarity would be a genuine sense of awe at what terrific marksmen these maniacs were. In those days my arse wasn’t anything like the size it would grow to be and, while never of a supermodel slimness, to land a dart almost centre-buttock from a moving car was little short of miraculous. If I had reported the incident I dare say the police would have narrowed the immediate search down to any army snipers on leave, but the fact is, I didn’t report it. In working-class areas in the late seventies people didn’t stride, or in my case hobble, to the local nick to alert the authorities there was a skylarking little mob with an air pistol on the loose, any more than the police expressed an interest in the tremendously common punch-ups in our local pubs. It just seemed to be part of the game. Compensation culture, trauma and counselling may be the options today, but back then if you got shot up the arse in front of your friends you simply had to take the gag on the chin, so to speak.

Those of you who bought the first book in this series may be wondering why, when that one ended with my earliest TV appearances in 1982, we’re now back in the late seventies again. Well, since

that book was published I have had countless friends and family members get in touch to say how come I hadn’t included this story or that tale in the covered time frame – especially those that took place away from the show-business spotlight (a beam that was about to start shining into my life with ever greater force during the eighties). For example the incident of which you have just read. How, various chums have enquired, could I possibly have omitted that saga from any serious history of the times? Was I ashamed of being shot twice, once up the arse, in Jamaica Road? Did I feel I was somehow to blame for it, had brought it on myself, and by burying the memory hoped to shut out the truth? How long should a man live with such a secret? By sharing with the world that I had been shot up the arse in Jamaica Road I hope now to help all those who have been similarly assailed. In that era, a sharp injury to the backside while colleagues looked on was seen as somehow humorous. Thank God, we’ve moved on since then. I believe it’s a tragedy that in the twenty-first century we still have no idea how many other innocent late-night revellers in the seventies took gunfire to the rump and have ever since kept this outrageous fact hidden from even their nearest and dearest. From another angle there might possibly be an argument that that well-aimed pellet to my rear in some way spurred me on to my later successes by forcing me to show there was so much more to me than a simple patsy who presented his buttocks as a challenge for

strangers’

firearms. Of course, nobody in the public eye would wish to be defined by the inevitable newspaper headline: baker: i was shot up the arse as a young man, accompanied as it doubtless would be by a photograph of myself looking grave but obviously relieved to have become unburdened. Yet how can I possibly hope to offer up a full picture of myself without including that awful night when I bent over in Bermondsey? I owe it to all of us who were shot up the arse back then and then suffered silently in the following years – particularly when sitting down too fast. I still have the small round scar which, if I position a mirror just so, I can gaze at and reflect upon those times in my life when not everything smelled as sweet as it does now. Maybe it is high time I

‘got

it out there’, as they say.

So, diligent chronicler that I am, though I will earnestly attempt to move the biographical arc forward over the next couple of hundred pages, forgive me if the narrative becomes somewhat off-kilter at times. The difference between life and fiction is that life doesn’t have to make sense. If by retrospectively dropping my trousers every few pages I can reveal a fuller picture of myself during these years, then so be it.

Besides. Being shot up the arse. In front of your mates.

Fucking hell. What else did I forget?