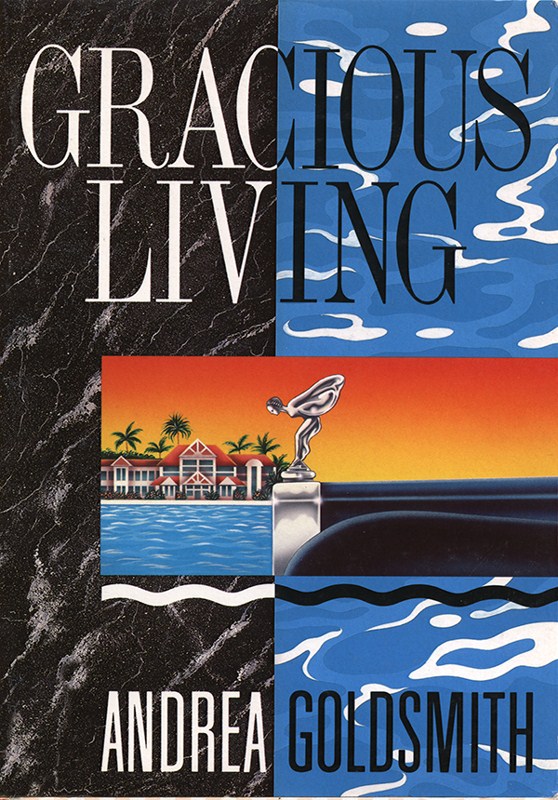

Gracious Living

Andrea Goldsmith was born in Australia in 1950 and educated in Melbourne where she took out degrees in speech pathology, sociology and philosophy. She has worked and travelled in the United States and Britain, has published short stories, and now lives in Melbourne.

Gracious Living

is her first novel.

ANDREA GOLDSMITH

Assisted by the Literature Board of the Australia Council

First published by Penguin Books Australia, 1990

Copyright © Andrea Goldsmith, 1990

Quotation from Patrick White’s

Eye of the Storm

with the kind permission of Barbara Mobbs and Jonathan Cape Limited

All Rights Reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Goldsmith, Andrea, 1950-

Gracious Living

ISBN 014 012755 0 (pbk)

I. Title

A823’.3

eBook edition published by Andrea Goldsmith, 2013

ISBN 9781742982847 (eBook)

eBook distributed by Port Campbell Press

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

Creative writing program assisted by the Literature Board of the Australia Council, the Federal Government’s arts funding and advisory board.

‘. . . perhaps the ordinary is

a better disguise for

ruthlessness.’

Patrick White,

The Eye of the Storm

For the first thirty years of her life Elizabeth Dadswell was tied to family, friends and background. She was married at twenty-one to Adrian Dadswell, who, with more ambition than ancestry, was not quite the husband her parents would have chosen; however, this being the late 1960s when so many sons of respectable families were going to ruin, they decided he would have to do. At twenty-three she became mother to a premature baby whose damaged brain defied the sweet destiny of pedigree. Such misfortune would have overwhelmed most people, but not Elizabeth who persisted with her exquisitely tailored life, struggled along in a fog of fatigue, until at a miserable thirty she asked herself, ‘What price love? What price heritage?’ and rifling through dreams dusty from neglect found no answers. At thirty-two she asked Adrian to leave and she and Ginnie, who was only nine at the time, set about making the house their home.

Elizabeth gave Adrian’s dun-coloured leather chair to the Salvation Army; she sold his desk to the plumber and bought a new bed. With the assistance of old Mr Jamieson the gardener, Elizabeth set up the new bed in the formal lounge, the room in which for the ten years of their marriage, Adrian had dispensed liquor and camaraderie to miscellaneous companions – some of whom were Elizabeth’s friends, many of whom were not. Adrian

dispensed alcohol and crudities and Elizabeth dispensed food and refinement. Adrian liked her to be present while he entertained, and so she was, until the teetering canopy of her marriage finally collapsed and she asked him to leave.

Adrian was annoyed, the marriage suited him and it should have suited Elizabeth; after all, she had everything – housekeeper, gardener, nice clothes, another child if only she were more sensible. He was also inconvenienced: in the midst of a big subdivision project he had more pressing things to do than look for a place to live. Elizabeth was being rash, he said, and should take time to reconsider. He suggested a week up north for her to relax and come to her senses, he even promised to join her for a couple of days; but she remained firm. He said she was being unreasonable and not at all refined. He said she would regret it.

But she did not.

And so he left. He left the woman he had married, the imperfect daughter he had fathered, the house his in-laws had bought: he left a life which had served him well. He also left the liquor cabinet, left it full. Elizabeth divided the contents between Mr Jamieson, who thought Adrian had a drinking problem, and Jack the plumber who had bought Adrian’s desk. With the alcohol neatly distributed, the cabinet became home to Elizabeth’s underwear. Now it stood in the former lounge alongside a cedar wardrobe and chest from the 1850s and opposite a delicate desk from a few decades earlier. Over on the western wall, in front of the bay windows, was an exquisitely carved couch where Elizabeth often sat, her shoulder-length auburn hair blending with the burnished wood. She would sit and look and admire this grand room with its great carved ceiling and marvel how, in the ten years since Adrian had left, his room had become her own. (For the first time it occurred to her: ten years married, ten years divorced – she was just about even.) As for the old bedroom, she had converted it to a studio and any remnants of Adrian were now smothered in clay and marble and sandstone.

Kate Marley, who had lived in the bungalow beyond the tennis court these past ten years, said the lounge-bedroom was far too sparse. ‘It looks bleak, lonely, people will feel sorry for you,’ – as

if a room were equivalent to a life. Elizabeth disagreed. How, she asked, could anyone pity her this room with its antique furniture, its crystal lamps, its marvellously intricate ceiling mouldings? How could anyone who had known her in the parched years of her marriage pity her? But it was easy, Kate said, people remember things not abstractions, and the things they remembered from Elizabeth’s marriage were her full, noisy house and her personable, if unfaithful, husband.

‘People remember what they thought you had, what you ought to have had,’ Kate continued. ‘To suggest you’re happy now is, in the minds of your old friends, a pitiable lie.’

But she was happy. Where others might see her tethered to loneliness, condemned to an unnatural post-marital spinsterhood, Elizabeth saw fulfilment. Others remembered the abundance, the things of her married life, while Elizabeth remembered an unleavened woman tracing the years in circles, hopes scudding to the horizon like leaves before the wind.

As for things, material things, she had always possessed them and still did. The cedar wardrobe and matching chest, the writing desk, the bookcases, the Charles Conder, the Grace Cossington Smith, a whole houseful of things remained, only Adrian was gone. So what did these eyes of judgement see? That she no longer had company at her dinner table? No one to accompany her to parties? And yet on such occasions Adrian had never stayed with her, always he went in search of more exotic game, leaving Elizabeth to play through a tired repertoire of pleasantries with an assortment of acquaintances. It wore her down after a while and people were heard to comment that pretty Elizabeth Dadswell was ageing badly, that poor Elizabeth Dadswell was being shrivelled by her sad heap of a daughter; what Elizabeth Dadswell needed, they all agreed, was another child, a normal one.

But she did not. She needed fewer people, not more. It was Adrian who was wearing her down; Adrian, whom she had regarded as essential, was pillaging her youth. That’s what neglect can do, that’s what pretence can do – and there were generous amounts of both. The neglect was simple: with the pressure of work and his affairs, Adrian spent very little time at home. As for

the pretence – pretending she knew nothing of his infidelities, pretending he loved his daughter – in those days she thought it was the right thing to do; besides, like her mother before her, Elizabeth did not believe in making scenes. As to whether he loved her, it became a moot point; in time he seemed not to notice her, just as he no longer noticed the wardrobe and chest, the writing desk, and the Cossington Smith.

When Adrian left and Elizabeth and Ginnie settled into their life together, weariness and torpor slipped away; Elizabeth gained a little weight and the premature wrinkles thawed. People were heard to mutter that Elizabeth Dadswell, always so prim and proper, had taken a lover – which she had not. At first she tried to explain that her former life, apparently so attractive, was a confected lie, and the man they found so amusing was a shallow clown, but her friends did not want to know, they did not want the truth about a life so very similar to their own. As for Ginnie, she was consumed by the disability as far as the friends were concerned. She had cerebral palsy causing slurred speech and cumbersome movements, and yet, her achievements were many: she had made the junior swimming team, was a top student, and a favourite with her peers. But to the gaze of the Dadswell friends, directed as it was by a firm belief in appearances, Ginnie was less than human. So Elizabeth, a long-time expert at concealment, stopped trying to explain her life. Within a few short months, refined, warm Elizabeth Dadswell was regarded as refined, a little less warm and somewhat enigmatic. Within a year she was described as private and withdrawn and no longer appreciative of old friends. So sad about Elizabeth Dadswell, people whispered behind manicured hands.

But in recent times the whispering had stopped. After a decade of counselling and assertiveness training, the old crowd never whispered, the old crowd spoke its mind and searched for new experiences. People studied her work, running their fingers over the sculptures trying to prise secrets from the stone. They bought her work, they said it made them feel good. Elizabeth Dadswell, former princess of the social set, had become a different sort of curiosity. Of course the old friends still pitied her, never having

experienced a mature relationship, never having known the beauty of normal motherhood, but they also envied what they described as her ‘own person’. ‘You are your own person,’ they said solemnly, ‘you’ve reached in deep and found yourself.’ Elizabeth Dadswell had regained her worth and once again the old crowd wanted to know her.

More than she wanted to know them, she thought as she rearranged her pillows and sat up. With her exhibition only a couple of weeks away, the idea of all those people eyeing her work was terrifying. She was about to get up and leave her fears with the early morning when she heard the squeak of the autotray from the passage. She smiled and settled back into the pillows.

‘Are you awake?’ It was Ginnie’s measured voice.

The autotray appeared in the doorway. Behind it, using the trolley in place of her walking sticks, was Ginnie. She crossed the room, her stuttering gait and the sculptured carpet playing havoc with breakfast.

‘Breakfast for two. Coffee, cold toast, slopped orange juice and yesterday’s mail.’

Elizabeth leaned forward and guided the autotray alongside the bed; she moved over and patted the spot next to her. Ginnie flopped down, fell back against her mother, kissed her and swung her wayward body to a sitting position.

‘You were late last night,’ Elizabeth said moving a glass of orange juice to within her daughter’s reach. ‘I thought you were going to Kate’s only for an hour.’

‘I was, but Kate was in top form – a fresh bottle of Scotch, Philip Glass on CD, and a cache of stories I’d never heard before.’ Ginnie drank the juice through a straw and took a piece of toast. She settled back against her mother’s legs and started to laugh. ‘Kate told me how she and Vivienne first met. What a joke boarding school must have been! Has she told you about it?’ Elizabeth nodded. ‘And Shakespeare’s sonnets, have you heard about them too? How she and Vivienne spent years studying them for clues that they were written to a man?’ Ginnie stopped to take a bite, chewed and tipped her head back to hasten a swallow. ‘Kate says the sonnets taught her about love. Sex too. It all sounded so old-fashioned,

two children learning about love from Shakespeare’s sonnets; more like the nineteenth century than,’ she paused a moment, ‘what would it have been? 1960? 1961?’ Elizabeth nodded, around that time. ‘Kate also told me Vivienne saved her life.’