Grand Opera: The Story of the Met (33 page)

Read Grand Opera: The Story of the Met Online

Authors: Charles Affron,Mirella Jona Affron

Everyone agreed: the sight lines and especially the acoustics had left the Old Met in the dust. The other shoe, admittedly less weighty, dropped with the art and architecture reviews. Ada Louise Huxtable, the distinguished architecture critic of the

Times,

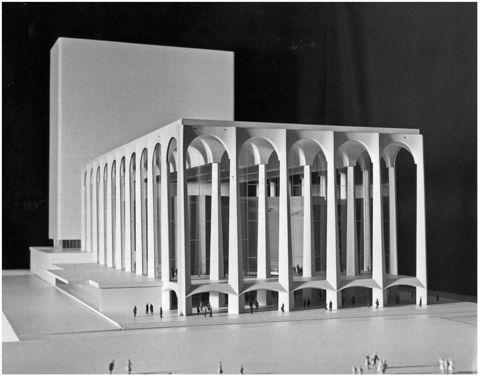

and John Canaday, its art critic, were in sync. The edifice, outside and in, was in Huxtable’s words “a throwback” and in Canaday’s “retardatory avant-gardism.” Huxtable began her column with a description of what might have been, still not a modern masterpiece, but significantly better than what actually was. The original design had called for “structurally independent stage and seating enclosed within an arcaded shell, the two separated by an insulating cushion of space.” Services, administrative offices, and work areas were to have been consigned to a tower west of the stage. The nearly ninety-foot-tall arcaded windows of the façade (an element that recalled the architect’s by now yellowed plans for the aborted Rockefeller Center opera house) were to have been continuous north and south. What emerged were essentially unadorned sidewalls. Many services were relocated to the spaces between the outer and inner shells. As to the interior, Harrison had pressed for a more modern design, but his client had insisted on middle-of-the-road solutions at every juncture. Huxtable recorded a “strong temptation to close [her] eyes.” Conceding, as all did, that hearing and seeing the opera came first, she concluded, “it is secondary but no less disappointing, to have a monument manqué.”

FIGURE 29

.

Model with side arcades and tower for the new house at Lincoln Center (K. Thomas; courtesy Metropolitan Opera Archives)

In his notice, Canaday checked off the art works chosen to embellish the building’s interior: three bronze statues by Aristide Maillol stood in immensely tall lobby niches; a bronze cast of Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s “Kneeling Woman” capped the double staircase. On the walls of one of the restaurants, “The Top of the Met” (nicknamed “Dufy’s Tavern,” or, alternately, “Bing’s Bistro”), hung murals by Raoul Dufy. They had belonged to the sets he designed for the New York run of Jean Anouilh’s

Ring Round the Moon

in 1951. But what attracted the most attention were the Marc Chagall murals “Les Sources de la Musique” and “Le Triomphe de la Musique,” which, incidentally, bore the semblances of Rudolf Bing and ballerina Maya Plisetskaya. These giant murals were an afterthought, a $300,000 attempt to cover the bare walls where the north and south arcades were to have been. Canaday thought them “hardly daring.” They might just as easily have been painted “forty years ago, or [by] any person with a nimble wrist and access to a set of color reproductions of Chagall’s recent (i.e., since 1930) work.” The object that drew the greatest fire was Mary Callery’s sculpture above the proscenium. Canaday had this to say: “nominally the most modern work in the place, but its weaknesses are such that only its placement, pinned up like a piece of junk jewelry, atop a proscenium arch that seems to have been built of gilded Nabisco Wafers, could lend it any illusion of weight and strength.” He concluded, “The Dufy murals may, in the long run, prove to be the most

successful decorations in the place, simply because they are the least assuming in a complex that, over-all, suffers from gassy inflation.”

FIGURE 30

.

Interior of Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, 1966 (courtesy Photofest)

Be that as it may, many who entered the opera house for the first time or gaped from the plaza through the glass walls were bowled over by its size, its glitter, and the glamour of the event. Ticket holders had been mailed a large silk-screen program that reproduced the red and gold color scheme of the house. They had contributed $400,000 to the Met coffers on this gala night, twelve times the take of an ordinary sold-out performance. The banquet list included Mrs. Lyndon Johnson, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos and Mrs. Imelda Marcos, various other foreign dignitaries, Ambassador to the United Nations Arthur Goldberg, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Governor Rockefeller, and Mayor Lindsay. Also present was John D. Rockefeller III, chairman of the Lincoln Center board, as were several Whitney and Vanderbilt descendants of the original founders. In attendance

as well was the daughter of Otto Kahn; no one had fought longer or harder than he to see this moment. On the plaza, cheering as the VIPs trod the red carpet, were hundreds of New Yorkers. Twenty-five protestors carried signs that read, “End the War in Vietnam.” They were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.

The joy of the occasion was dampened by worry over the strike called for the day after opening night. That the continuation of the season was in jeopardy had been well publicized. When the 1964 contract was up for renewal, rather than press for a new agreement the orchestra opted for a two-year extension to 1966. The union strategy was to defer the 1964 battle in favor of an all-out offensive timed to coincide with the Lincoln Center opening. Bing would then presumably find it impossible to hold the sword of cancellation over the heads of the musicians. The orchestra would have the upper hand. Its demands included a reduction in obligatory weekly performances from seven to five, improved health insurance and pension benefits, and five weeks of annual vacation. The cloud that hovered over September 16 was lifted during the second intermission of the world premiere of

Antony and Cleopatra

when Bing took the stage to announce that the strike had been averted. This real-life coup de théâtre was met with the longest ovation of the evening.

September 16, 1966;

Mourning Becomes Electra,

March 17, 1967

Bing and his artistic team had concocted a stupendous opening season replete with nine new productions, an astounding four in the first eight days. The plan proved to be madness.

Antony and Cleopatra

and

Die Frau ohne Schatten

were company premieres; their novelty was the least of the leaps into the unknown. Each of their designers wanted to put the exciting new stage machinery through its paces. Particularly irresistible was the vaunted turntable, built by an outfit that produced platforms for revolving rooftop restaurants. In

Antony and Cleopatra,

the disk was to carry a huge sphinx surrounded by three hundred marching Egyptians. It was to move forward while rotating. But when the switch was finally thrown during rehearsal, the turntable refused to budge; someone had miscalculated the maximum load by a factor of ten. The overtaxed crew was put to work retrofitting the sphinx so that it could be turned by stagehands hidden within. The repair of the

turntable would take nearly four years. Then there was the matter of the schedule, regularly disrupted as one director worked to solve an unanticipated problem and another, along with cast, orchestra, and chorus, waited, sometimes for hours. The principal culprits were the sixteen complex scene changes of

Antony and Cleopatra

. An anxious management piled rehearsal on rehearsal at the expense of the other productions. The company was exhausted, as was Bing’s purse, by the unbudgeted overtime. The first week’s calendar had to be adjusted, to the great annoyance of ticket holders.

Antony and Cleopatra

opened as promised.

La Gioconda

was delayed by three days,

La Traviata

by two, and

Die Frau ohne Schatten

by more than a week. Bing took the blame: “The fault was mine. I had overplanned the season.”

7

Conductor Thomas Schippers had urged Barber to base his next opera on

Antony and Cleopatra,

the composer’s “favorite” play. Franco Zeffirelli agreed to adapt the text and design and stage the production. Bing would assemble a brilliant, (nearly) all-American cast led by Puerto Rican Justino Díaz and Mississipian Leontyne Price. The stage and its machinery would be shown to spectacular advantage. Everything seemed right. Nearly all of it went wrong. There was the glitch of the turntable and, again during rehearsal, the entrapment of Price inside the pyramid, not to mention her imprisonment in grotesquely outsized costumes. Crowds of choristers and supers engulfed her and the other principals. Zeffirelli framed it all—the sphinx, a barge that moved forward from the stage’s distant back wall, and his signature menagerie, here a camel, goats, and horses—in shifting patterns defined by metallic rods. The melding of abstraction and realism resulted in a gaudy hybrid that overwhelmed the music and the drama. The critics outdid one another in bashing Zeffirelli’s production: “Almost everything about the evening, artistically speaking, failed in total impact . . . a lavish, but completely unoriginal concept that smothered in its own production”; “Appallingly pretentious, appallingly arty, and, in most respects, destructive”; “a disaster.” As for the music, one reviewer went so far as to accuse Barber of dealing “a severe blow to the hopes of American opera by denying it the prestige it might have had.

Antony and Cleopatra

is a slick, chic, fashionable opening-night opera, when what was really needed was an opera for all seasons. It could have been both.” Little wonder that Barber’s composition breathed its last at the Met after only nine performances.

8

Price was no less an inspiration for the score than Shakespeare for the libretto. The soprano had been Barber’s interpreter and friend since the 1950s, when she sang the premiere of his “Hermit Songs.” In the words of the composer, “Every vowel was placed with Leontyne’s voice in mind. She is all

impassioned lyricism. I had a problem just keeping her off stage.” Far too often, however, he called upon her “ ‘Carmen’ voice” (

Times,

Aug. 28, 1966), her harsh low register to express Cleopatra’s rage. But when given the chance to carve a soaring line in the upper octave, and then to perch on a high note, Price was at her resplendent best.

FIGURE 31

.

Antony and Cleopatra

, act 2, scene 4, center left to right, Justino Diaz as Antony, Leontyne Price as Cleopatra, Ezio Flagello as Enobarbus, 1966 (Louis Mélançon; courtesy Metropolitan Opera Archives)

Antony and Cleopatra

had broken the bank and the promise of a triumphant opening night. To add insult to injury, the New York City Opera put on Handel’s

Giulio Cesare

a little more than a week after the Barber premiere. The acclaimed production and Beverly Sills’s wondrously sung Cleopatra made a mockery of Bing’s dismissal of the troupe next door as “provincial.” The poor relation on Lincoln Center Plaza had let it be known that it would give the Met a run for its money.

For the final new production of his showcase 1966–67 season, Bing offered the world premiere of another American opera. Agamemnon’s family

imploded in Martin David Levy’s expressionistic

Mourning Becomes Electra

as it had six months earlier in the

Elektra

of Richard Strauss. Henry Butler’s skillful adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s gargantuan play, Boris Aronson’s remarkable ruin of the Mannon mansion, the entire cast, the staging of film director Michael Cacoyannis, and the conducting of Zubin Mehta gave the work its best shot at success. Reviewers agreed that Levy’s suppression of his bent for melody was all too obvious. Thirty years later, when the Lyric Opera of Chicago put on his revised version, the composer confessed that in 1967 he had “felt intimidated” by the fashionable “hard-liners” (

Times,

Oct. 13, 1998). But despite its flaws,

Mourning Becomes Electra

had made great theater even way back then.

Two weeks before his first night, Giulio Gatti-Casaza announced that the Met would at last present an American opera, Frederick S. Converse’s

The Pipe of Desire

. Soon after, the impresario persuaded the board to fund a $10,000 prize for a new work by an American-born composer. “I am convinced,” he declared, “that there is enough musical talent in this country to justify a movement in favor of an American grand opera, and I am sure that if the movement is properly organized we shall be able to have operas worthy of the name” (

Times,

Nov. 21, 1908). In his 1925 “Statement,” Otto Kahn thought it politic to recognize the Italian intendant’s Americanization of the company; Gatti had introduced nine American operas in seventeen years. Kahn neglected to mention the anemic total of thirty-nine performances they had registered; and only two productions had survived into a second season. He elided also the point later made by Frances Alda in her witty account of a rehearsal of Walter Damrosch’s

Cyrano:

“I had just finished my first duet with [Pasquale] Amato. The pencil marks on my score were misleading. ‘Where do we go from here?’ I asked Amato. Before he could reply, [Richard] Hageman, the assistant conductor, who was rehearsing us, spoke up: ‘From Gounod to Meyerbeer.’ ” At its 1937 Met premiere, Hageman’s own

Caponsacchi

would be savaged for its borrowings. Gatti let six years elapse between Henry Hadley’s 1920

Cleopatra’s Night

(starring Alda) and 1927 when Deems Taylor’s

The King’s Henchman

became the first American opera to reach double-digit iterations. Before Gatti left in 1935, there were only two more.

9

As time went by, the stubborn hope that America would find its operatic voice was repeatedly dashed. On October 15, 1935, Edward Johnson informed

the board that he had obliged the Juilliard mandate by examining twenty-nine American scores; only Vittorio Giannini’s

The Scarlet Letter

and David Tamkin’s

The Dybbuk,

one saddled with a poor libretto, the other too costly, got as far as a second look. Like Krehbiel and Henderson before him, Olin Downes was an advocate for American opera in the abstract and a feared critic in the particular. Still, as director of music for the World’s Fair, he pitched revivals of

Cyrano, The Emperor Jones,

and

Amelia Goes to the Ball

for the Met’s special 1939 spring season. An all-Wagner program won the day. In 1941, the Carnegie Corporation of New York awarded grants-in-aid to composer William Schuman and librettist Christopher LaFarge so that they might learn the workings of the opera house from within. Their residency produced no tangible result. Johnson managed only six indigenous entries.

Newsweek

summed it up: “As far as American opera at the Metropolitan is concerned, the years have shown it to be a case of damned when it does, and damned again when it doesn’t” (Jan. 20, 1947).

10

As for Bing, neglect of American titles (he trotted out a pathetic four in twenty-two seasons) was just one aspect of the hidebound programming of which he was justly accused. When confronted with the choice of

Vanessa

or Louise Talma’s twelve-tone score for Thornton Wilder’s

The Alcestiad,

he opted for the less-taxing Barber-Menotti collaboration. Bait came in the form of a Ford Foundation grant: Ford pledged to commission three operas of composers selected by the company, any one of which could be rejected by the Met whatever the stage of its development. If chosen for production, the Foundation would cover the difference between the box-office receipts of the new opera and those of a popular title. The financial risk was negligible. But there was a downside, as Gutman noted: “If it finally should turn out that none of them is considered worthy of a Metropolitan production, it would not only be a very bad position in terms of our public relations but would also be an outspoken disservice to the cause of American Opera, which of course we ought to avoid at all cost.” The projects of a number of proven composers were considered, among them those of Sergius Kagen, Norman Dello Joio, Nicholas Flagello, William Grant Still, Douglas Moore, Roger Sessions, Marc Blitzstein, and Barber and Levy. Moore gave

The Wings of the Dove

to the New York City Opera in exchange for assurances of production. Sessions’s work was “not sufficiently advanced for him to show any part of it.” Bliss authorized an additional sum for Blitzstein’s

Sacco and Vanzetti;

at the composer’s death in 1964, the score was still incomplete. In the end, Ford underwrote

Antony and Cleopatra

and

Mourning Becomes Electra

. Bing never again

ventured onto the home field. It was not until December 19, 1991, that the company mounted a new American work, John Corigliano’s

The Ghosts of Versailles

. In the new millennium, rising enthusiasm for products “made in the USA” has been generated primarily in other theaters.

11

TABLE 13

Metropolitan Premieres of American Operas,

1910–11

to

2012–13