Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (45 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

Only one foreign visitor in these years seemed ready to resist his increasing tendency to translate his experience into dogma. Margaret

Sanger, the founder of the movement that became Planned Parenthood, a proponent of enlightened female sexuality and contraception, stopped by in January 1936 for a conversation in which she stressed the life-enhancing nature of sexual intimacy for women as well as men.

As might have been expected, Gandhi took an opposing view, expounding on brahmacharya as a spiritual discipline; his conversation with the American—unlike any he’d previously had with a woman—seems to have sent his worrisomely high blood pressure higher and, by some accounts, left him in a state near nervous collapse.

Physically and emotionally, he was already nearing the edge. A little more than a year after he arrived in the district, Gandhi had decided that it wasn’t enough for him to assign his disciples to settle in the most remote villages in a remote district. He needed to understand why they found it such hard going. Typically, he instructed them to begin their missions of service by volunteering as village sanitation officers and scavengers (scooping up human excrement wherever it was to be found, usually beside rural pathways, and then digging proper latrines). The example was not always as effective as he expected. “

The people are completely shameless,” wrote his faithful secretary and diarist,

Mahadev Desai, whose duties included serving as a one-man cleanup detail in an exceptionally unresponsive village called Sindi. “They do not have any feeling at all. It will not be surprising if within a few days they start believing that we are their scavengers.”

Gandhi concluded there was only one way for him to understand why villagers were proving so impervious to the selfless example his satyagrahis set before them. What was needed was for him—the man recognized by most of India and most of the world as the country’s leader—to settle in a village and live there all by himself, with none of his usual entourage. It made perfect sense to Gandhi but not to his closest associates, who were already nervous about his health and jealous of any change in the Mahatma’s life that would limit the time they got to spend in his presence.

The village he selected in Wardha district for this latest of his “experiments with truth” was then called Segaon. It happened to be adjacent to orange and mango orchards owned by an important backer and underwriter of the Mahatma, a wealthy trader named

Jamnalal Bajaj who’d been, in the theatrical sense, the angel who produced Gandhi’s relocation in Wardha and the host who’d provided lodging for the Mahatma and his entourage. Bajaj also owned the land on which Segaon’s untouchables—two-thirds of its population of over six hundred—

huddled; the revenues he collected from the village would subsidize Gandhi’s latest experiment.

No road, as yet, connected Segaon to the district’s market town, four miles away. India’s leader arrived there on foot on April 30, 1936, and, two days later, told the villagers of his intentions. “

If you will cooperate with me,” he said, “I shall be very happy; if you will not, I shall be content to be absorbed among you as one among the few hundred that live here.” As related by Mirabehn, the headman, “

a very charming and aristocratic old man, made a graceful and honest speech in which he welcomed the idea of Gandhi coming to live amongst them, but made it quite clear that he personally would not be able to cooperate in Bapu’s Harijan program.”

The hut that he was to occupy, on Segaon’s outskirts, had yet to be completed, so that night a makeshift tent was strung up for him under a guava tree. Since there were wild animals in the area—cheetahs, panthers—a trench had to be dug around the patch of ground on which the Mahatma was to sleep. Using the excuse that they were overseeing the completion of his dwelling, several of his entourage slept beside him.

As might have been expected, the Mahatma’s ambition to spend a night alone in Segaon would never be fulfilled. Before long, the whole entourage, amounting at times to nearly a hundred persons, was ensconced there. He’d not planned to make his dwelling the center of an ashram, but that’s what it became. Thanks largely to Jamnalal Bajaj’s generosity, new buildings went up, a road was put through and, eventually, even a phone line so the Mahatma could be reached by the viceroy’s offices in New Delhi and the hill station of Simla, to which the top echelons of the Raj retreated in summer when Wardha broiled. Segaon, the village Gandhi briefly intended to make the focus of his energies, inevitably became a sideshow. Fittingly, after March 1940, it would take the name of the ashram that had spontaneously mushroomed alongside it.

Ashram and village were both called Sevagram, meaning “Village of Service.”

The growth of the ashram was less than a mixed blessing, becoming another distraction from the village work that had drawn him to Segaon in the first place.

“Oh God,” Gandhi said, “save me from my friends, followers and flatterers.”

Today the nearest village houses are around the bend of a dirt road, a couple hundred yards from the ashram, a complex of dark wood structures with long sloping roofs that give an appearance reminiscent of a Buddhist monastery in Kyoto. Sevagram the ashram no longer serves

Sevagram the village. With a bookshop, a canteen, and even some modest rooms to rent to pilgrims, it maintains itself as a tourist attraction. The village still looks poor, but some of the houses have TV antennas on their roofs and motorbikes leaning up against their cracked and mildewed cement walls. The houses stand on land that Bajaj signed over to Gandhi and Gandhi signed over to the village’s untouchables, who now call themselves

Dalits rather than Harijans. When you stroll from the ashram to the one village that received more personal attention from the Mahatma than any other among the 700,000 that existed in his India, a statue comes into view beside a sports field. The figure on the pedestal is not wearing a loincloth. He’s wearing a suit painted an electric shade of blue and a painted red tie. It’s the figure of Babasaheb Ambedkar. And the former untouchables in what was once Gandhi’s chosen village—especially the younger ones—are likelier, when asked, to identify themselves as Buddhists than as Hindus.

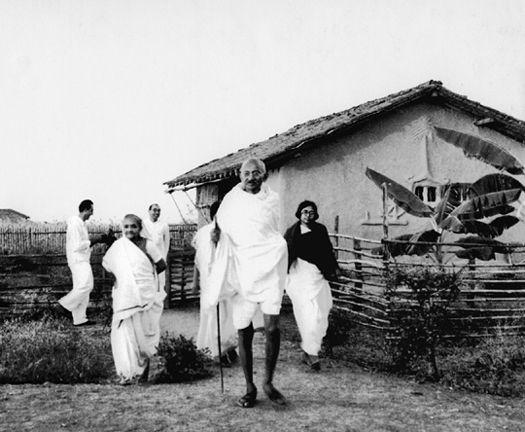

Ashram grew up around Gandhi as Sevagram

(photo credit i10.1)

For most of Gandhi’s first year in Wardha, he’d been less preoccupied with the actual human condition in the surrounding villages than with the task of birthing a new mass organization he’d dreamed up to infuse

badly needed energy into his languishing campaign for village self-sufficiency through hand spinning and

weaving. He’d invested excessive faith in the spinning wheel, the iconic charkha, as an invincible panacea for village poverty, he now concluded. By itself, it would not be enough to lift rural India out of its misery. Spinning and weaving would retain their place, but they needed to be supplemented by a whole array of traditional crafts that were losing out in competition with processed and manufactured goods being produced more cheaply in city factories and workshops. Villages had once known how to turn out their own handmade pens, ink, and paper; they ground their grains into flour, pressed vegetables for their oils, boiled unrefined sugar, tanned hides into leather, raised bees, harvested honey, ginned cotton by hand. For their own salvation, they needed to do so again, Gandhi taught; and it was a national need to support them not only by wearing homespun khadi but by consciously giving all they produced a preference over manufactured articles, to undo as far as possible the ravages of the Industrial Revolution.

Starting from these premises, the nation’s leader suddenly had an urgent need to know whether hand-pounded rice and grain could be shown to be more nutritious than the polished products from the mills. Could hand-husked rice compete in price with mill-husked rice? What use could be made of the husk? Did spinning pay better than husking? Could oil be harvested from orange rinds?

Gandhi’s letters were full of such questions; in his mind, the answers he received were building blocks of a revised strategy for gaining “the swaraj of our dreams, devoted to the welfare of villages.” His new organization needed a constitution, advisers, and a board that would be selfless and nearly full-time; it needed a table of organization reaching down to every district and, ultimately, every village in the vast country. Within a couple of months Gandhi had created all this, on paper at least, and the

All India Village Industries Association (AIVIA) came into existence with its national headquarters in previously obscure Wardha, in a building donated, of course, by Gandhi’s angel, Bajaj. Gandhi recruited a chartered accountant from Bombay, with postgraduate training in economics from Columbia University, to serve as the organization’s director.

A Christian, he was known at Columbia as Joseph Cornelius; by the time he got to Wardha, where he stayed until after Gandhi’s death, he had become J. C. Kumarappa. Today Kumarappa is occasionally mentioned in India as a pioneer theorist on sustainable farming and appropriate technology;

the last Western economist who seems to have been conscious of him or Gandhi as thinkers with something useful to say about

the world’s poorest was

E. F. Schumacher, himself a dissenter from orthodox development doctrines whose book

Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered

enjoyed a brief vogue when it appeared in 1973, twenty-five years after Gandhi’s death.

The Mahatma denied that his fixation on village industries betokened any dilution of his campaign against untouchability, just as he’d denied a decade earlier that his renewed emphasis on the charkha represented a backing off from his campaign for Hindu-Muslim unity. Many of the spinners were untouchables, he pointed out. There was conspicuous overlap between AIVIA and other organizations he or his followers had launched to advance the Gandhian constructive program in the 700,000 villages: the recently formed Harijan Sevak Sangh, the intended beneficiary of the anti-untouchability tour; the older

All India Spinners Association; the

Gandhi Seva Sangh, brought into existence by the Congress to further the constructive program to which it paid lip service (not to mention the

Goseva Sangh, an association for the

protection of cows for which he’d become a patron). For most of these, the lawyer who’d last practiced in Johannesburg drafted constitutions and designed management structures, just as ever since 1920 he had for the

Indian National Congress itself. AIVIA’s basic document didn’t hesitate to articulate a principle that all these organizations implicitly held in common. “

The Association,” it declared, “shall work under the guidance and advice of Gandhiji.” The movement with the largest outreach, the spinners association, boasted that it had penetrated 5,000 villages, but this was a mere fraction of 1 percent of the 700,000.

All the Gandhian organizations shared a common defect: a reliance, in theory, on selfless village interns—in Gandhi’s terms, satyagrahis—and the absence of any sure method for discovering, recruiting, training, or sustaining such a vast army of inspired, literate workers uninhibited by inherited constraints of caste. “

Full-timers, whole-hoggers, with a live faith in the program and prepared immediately to make the

necessary adjustment in their daily life,” he said, describing the attributes of the committed workers he sought as if he were placing a classified ad. The “necessary adjustment” would be to lower—drastically—their citified standards of living. They would need to cultivate a life of “rigorous simplicity,” he said. What the Maoist leadership in

China would seek to do through terror, commands, peer pressure, and relentless ideological drilling when it launched its “down to the countryside” campaign during the Cultural Revolution three decades later, Gandhi hoped to achieve by inspirational example, his own and that of his closest followers. “Workers

without character, living far above the ordinary life of villagers, and devoid of the knowledge required of them for their work can produce no impression on the villagers, whether Harijan or other,” he said. “If every one of such workers puts on his work a price which village service cannot sustain, ultimately these organizations must be wound up.”

Even his closest followers had doubts. “What is the advantage of this work?” Mahadev’s son boldly asked the Mahatma. “There is no effect on the villagers. On the contrary they go on giving orders to us to clean various places.”

“

So! You are already tired!” Gandhi retorted in mock exasperation. He then offered pointers on how the work might be accomplished: “If I am in your place, I will observe carefully. If someone gets up after easing himself, I will immediately go there. If I see any rottenness in the excretia I will tell him gently, ‘Your stomach seems to be upset; you should try a particular remedy,’ and thus I will try to win him over.” After scooping the turds, he went on, he’d then plant flowers on the site and water them. “Cleanliness can be an art,” he concluded.

Even at his most visionary, he sometimes lets slip a bleak forecast of what’s likely to prove possible, as if steeling himself for disappointment, for a noble failure, as he sets out. “If [the villagers] abuse us,” he preaches to his acolytes when only beginning to contemplate the idea of living in a village himself, “let us bear it in silence … Let the people defecate wherever they choose. Let us not even ask them to avoid a particular place or go elsewhere. But let us go on cleaning up without a word …