Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (49 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

Now, in the month they had together in 1937, Gandhi eagerly entered into a discussion of the rights and wrongs of Arab-Jewish strife in Palestine. He’d had a

firm position on the subject since 1921, at the high tide of the Khilafat movement. Basically, his position was that Indian Hindus ought to support their seventy million Muslim brethren on what was for them an issue of religious principle. His friend urged him to pay sympathetic attention to the Zionist side of the argument. Gandhi promised he would. Kallenbach then had the

Jewish Agency furnish the Mahatma with a twenty-five-page essay on the historic, spiritual, and political underpinnings of Zionism, prepared especially for him. “

The sender’s name is not given,” Gandhi noted, but he found the piece “very impressive, deeply interesting.” So impressive that he was moved to consider proposing an effort to mediate between Arabs and Jews under his supervision, with Hermann Kallenbach, now back in Johannesburg, as his lead mediator. “

I quite clearly see that if you are to play any part in bringing about an honorable settlement,” Gandhi writes the architect, “your place is in India.” Apparently concerned that his friend might suspect that pressure was being applied for personal reasons, Gandhi adds: “All this I say irrespective of the domestic arrangement between us.” Gandhi himself seems as ardent as ever. His wishes are unambiguous, but with what seems an effort, he practices restraint. “I must not force the pace,” he writes to his friend in Joburg a half year later. “You must come in your own good time.”

After Kallenbach’s return to South Africa, Gandhi had turned his hand to distilling his view of the problem in a draft he sends on to his Zionist friend for his approval. “

In my opinion the Jews should disclaim any intention of realizing their aspiration under the protection of arms and should rely wholly on the goodwill of Arabs. No exception can possibly be taken to the natural desire of the Jews to found a home in Palestine. But they must wait for its fulfillment till Arab opinion is ripe for it.” Gandhi basically wants the Jews to become satyagrahis, the Arabs too. Kallenbach, half won over, sends the draft on to Chaim Weizmann. It’s never published.

His offer to mediate in Palestine is just a beginning. At a time when the Mahatma feels increasingly stymied in his efforts to reform India, he becomes increasingly inclined to issue encyclicals on international problems. Obviously, his frustration at home is not the only reason for his readiness to speak out. The world is hurtling toward catastrophe, and as the appointed keeper of the doctrine of nonviolence he feels a responsibility to make himself heard. A series of moral pronouncements flows

from his humble quarters near Segaon. In all, they are a mixed bag, full of trenchant moral insights, desperate appeals, and self-deluding simplicities. A subsequent statement on Palestine draws an anguished rebuke from the theologian

Martin Buber, a refugee from Hitler who has become prominent in the earliest version of a Jewish peace movement.

Buber writes that he “has long known and honored” Gandhi’s voice, but what he hears on Palestine he finds “barren of all application to his circumstances.” He then goes on to dissect a pronouncement of the Mahatma’s on German Jews. Gandhi has prescribed satyagraha as the answer to Nazi barbarism. He has found “an exact parallel” between the plight of the Jews under Hitler and that of the Indians in his time in South Africa. Buber tells Gandhi he lived under Nazi rule before becoming a refugee and saw Jewish attempts at nonviolent resistance. The result was “ineffective, unobserved martyrdom, a martyrdom cast to the winds.”

There’s reason to believe that Buber’s letter, dispatched to Segaon from Jerusalem in March 1939, never reached Gandhi. In any case, by then the Mahatma had already left a distressing trail of futile, well-intentioned missives. He’d written to the Czechs on the uses of satyagraha to combat storm troopers and to the viceroy, offering to mediate between Hitler and his Western prey, including Britain. Within several months, he’d write the first of two letters to the führer himself. “

Will you listen to the appeal of one who has deliberately shunned the method of war not without considerable success?” he asked rhetorically, in a desperate, naive mix of humility and ego. The British, who monitored his mail, made sure the letter went nowhere.

The letter to Hitler began with the salutation “My friend.” Hitler had already indicated what he thought of the Mahatma and his nonviolence. “All you have to do is to shoot Gandhi,” he advised a British minister.

Eventually, after the outbreak of war and his own final imprisonment, Gandhi would write to Churchill offering his services in the cause of peace. “

I can’t imagine anyone with Gandhi’s reputation writing so stupid a letter,” a new viceroy, Lord Wavell, confides to his diary after intercepting it.

Unrealistic, self-regarding, and dubious in their reasoning as most of these letters were, Gandhi’s basic understanding of Churchill’s “gathering storm” wasn’t always unfocused. “

If there ever could be a justifiable war in the name of and for humanity, a war against Germany, to prevent the wanton persecution of a whole race, would be completely justified,” he wrote. “But I do not believe in any war.”

The onetime sergeant major had volunteered as a noncombatant in the Boer and Zulu wars. He’d offered to serve as the “recruiting agent-in-chief” for the viceroy at the end of the previous world war, even inscribing himself as a candidate for enlistment at the age of fifty. Now, for the first time, he was striking a truly pacifist stance. This can only be understood in the Indian context. The looming issue was whether the national movement could barter its support for the war effort in exchange for a reliable promise of freedom. Put another way—in the way most Indian nationalists at the time understood it—the pivotal issue was whether India could be asked to fight for the freedom of the colonial power when the colonial power’s commitment to India’s freedom was still uncertain. Gandhi’s dogmatic pronouncements on the application of satyagraha to the Jewish-Arab conflict and the menace of

Nazi Germany can best be interpreted as trial runs for the penultimate chapter of the Indian struggle. It was as if he sensed that he’d be called back one last time from Segaon to lead his movement, and that this time he might have to put aside whatever lingering loyalty he might still have felt to the British.

However, when Britain finally entered the war, following the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939, Gandhi’s immediate instinct was to tell the viceroy that he viewed the struggle with “an English heart.” This viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, had proclaimed India’s entry into the war the previous day without consulting any Indian. Summoned to the Viceregal Lodge in Simla, Gandhi had offered no protest, not even a mild complaint, over this stunning oversight—stemming from habitual presumption and a calculated refusal to negotiate—that would soon ignite a prolonged struggle between the colonial authority and the Indian national movement. Eventually, perhaps inevitably, but only after much wavering, Gandhi would again take on the mantle of leadership to set out the strategy for that confrontation. It would pit him against the British at the height of the war. But in Simla the day after the viceroy’s declaration, under the illusion that he had established a warm personal tie to Linlithgow—not unlike what he sentimentally imagined his tie to Smuts to have been a quarter of a century earlier in South Africa—Gandhi by his own testimony “broke down,” shedding tears as he pictured the destruction of the houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, and the heart of London. “

I am in perpetual quarrel with God that he should allow such things to go on,” he wrote the next day. “My nonviolence seems almost impotent.”

MASS MAYHEM

B

Y THE END

of his seventh decade, Mahatma Gandhi had been forced to recognize that the great majority of his supposed followers hadn’t followed him very far when it came to what he’d listed as the four pillars of swaraj. The last and most important of these was supposed to be ahimsa, or nonviolence, which for Gandhi was both a core religious value and his set of patented techniques for militant resistance to injustice. Now, with the eruption of another world war, he was forced to recognize that “

Congressmen, barring individual exceptions, do not believe in nonviolence.” It would be his lot “to plough a lonely furrow,” for it seemed he had “no co-sharer in the out-and-out belief in nonviolence.”

Here the Mahatma seems to be deliberately striving for pathos. It’s a favorite posture, that of the isolated seeker of truth, and it’s not untinged with moral and political pressure, a whiff of emotional blackmail; his closest associates are left to feel guilty over their failure to measure up to his high ideal. Increasingly, this self-portrayal comes to define his sense of his inner reality as well as his political position. He can still draw huge reverential throngs, has a loyal entourage hanging on his every word and wish, but there are intangible, evidently important ways in which he feels himself to be alone. If Gandhi the prophet is to be taken at his word here, the temple of swaraj as he’d conceived it had now collapsed with the crumbling of its last pillar.

But the prophet’s declaration of his “out-and-out belief” doesn’t remove the political leader from the scene. Gandhi is never more elusive or complex than he is in this final decade of his life and career as he strains to balance his own precepts, values, and self-imposed rules with

the strategic needs of his movement. It’s a strain that only increases as power is seen to be within its grasp. From wrenching questions about the uses of nonviolence in a war against fascism (but not imperialism, as India was quick to catch on) to the just-emerging issue of what he’d term “vivisection”—the carving out and renaming of India’s Muslim-majority areas as a state called

Pakistan—Gandhi would regularly manage to stand on at least two sides, distinguishing his personal position from that of his movement, before stepping forward at the last hour to offer his loyal support for the position of the movement, and then, almost as regularly, stepping back.

As early as 1939, he drew a distinction between himself and his supporters who “want to be true to themselves and to the country which they represent for the time being, even as I want to be true to myself.” The idea that country and what he’d long since been used to calling “truth” could pull in opposite directions was a relatively new one, a source of profound inner conflict.

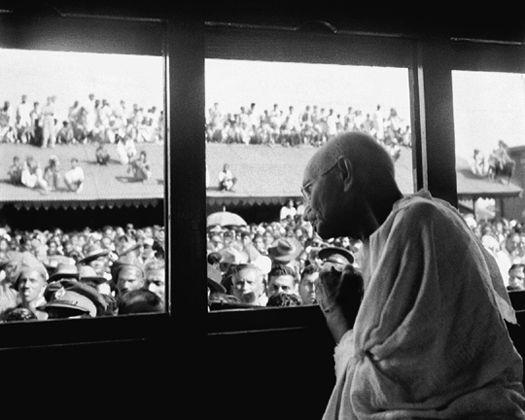

Again on tour, 1940

(photo credit i11.1)

To a bluff British general like Lord Wavell, the penultimate viceroy, it was all an act. Gandhi was a “malevolent old politician, who for all his sanctimonious talk has, I am sure, very little softness in his composition,”

Wavell wrote after his first encounters with the Mahatma. Had the viceroy’s skepticism been anywhere near the mark, the climax of Gandhi’s career would amount to little more today than an extended footnote, a kind of tributary to the torrent of onrushing events he tried and largely failed to influence. Instead, Gandhi’s last act can be read as a moral saga in its own right, not unworthy of the rubric “tragic” in its fullest, deepest sense. The public issues with which he wrestled retain their importance, but what stands out after all these years is the old man himself as he goes through a series of strenuous self-imposed trials in a time of national crisis, veering at the end of his life between dark despair and irrepressible hope.

If readiness to offer up one’s own body and life—what he called

“self-suffering”—were the mark of a true votary of Gandhian nonviolence, a true satyagrahi, then the Mahatma’s lonely, detached, largely ineffectual last years and months can be invested with grandeur and interpreted as fulfillment. Which was one of the ways that Gandhi, shaping his narrative as always, was inclined to see it. The premonition that he might meet an assassin’s bullets became a persistent leitmotif of his private ruminations. More than five years before his actual end in a New Delhi garden on January 30, 1948, he imagined his assailant would be a Muslim, despite all he’d done since the “glorious days” of the Khilafat movement, when, in his recollection, dignity and “nobility of spirit” reigned. “

My life is entirely at their disposal,” he said. “They are free to put an end to it, whenever they wish to do so.” Perhaps he was thinking back to the

slaying of his fellow mahatma Swami Shraddhanand at the hands of a Muslim extremist in 1926. His foreboding proved to be partly misplaced. It anticipated the circumstances of his death but not the motive behind the eventual plot or the identity of the plotters. It was Hindu extremists who targeted him. They saw him as pro-Muslim.

At the same time, the tragic narrative can’t be easily disentangled from the self-staged, nearly comic subplot of the Mahatma’s ins and outs—his repeated exits from leadership of the national movement and his sudden returns. In the months and years following the viceroy’s declaration of war on behalf of an India he never bothered to consult, Gandhi’s comings and goings get to be like the old stage routine of a performer holding up one end of a very long ladder while exiting stage left, only to reenter stage right an instant later, hoisting the other end.