Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (53 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

So also on that same day, hours before announcing at his evening prayer meeting his new plan to tour the district walking through its harvested paddy fields and over its rickety bamboo bridges, he sent a telegram to a nephew, Jaisukhlal Gandhi, whose young daughter Manu had nursed the Mahatma’s wife nearly three years earlier as she faded from life in detention and finally died of heart failure. Now a shy and unaffected seventeen with an appearance that could not be called striking, the devoted Manu had become a favorite pen pal of Gandhi, who coaxed and cajoled her to rejoin his entourage, all the while insisting he only wanted what was best for her.

The telegram to her father was oddly worded. It said: “

IF YOU AND MANU SINCERELY ANXIOUS FOR HER TO BE WITH ME AT YOUR RISK, YOU CAN BRING HER

.”

Gandhi made it sound as if he were giving way to the wishes of father and daughter. In fact, he’d planted the idea himself and cultivated it in an

epistolary campaign spanning months. “

Manu’s place can be nowhere else but here by my side,” he’d written.

It soon became obvious that the Noakhali Gandhi was now bent on making his young relative his primary personal attendant, the person who’d monitor his daily schedule, see that he was fed exactly what he wanted, measured out precisely in ounces (eight ounces boiled vegetables, eight ounces raw vegetables, two ounces greens, sixteen ounces goat’s milk boiled down to four ounces), at exactly the desired time; not only that, the person who’d administer his daily bath and massage, which could take longer than an hour and a half. An ounce of mustard oil and an ounce of lemon juice had to be mixed for the massage, which proceeded “in exactly the same manner every day,” according to a memoir Nirmal Bose later wrote: “first one part of the body, then another … in invariable succession.”

Even that could be considered just the beginning. It turned out that Manu Gandhi would also be expected to play the female lead in the brahmacharya test the Mahatma now saw as essential to his self-purification. Starting in the late 1930s, he’d had female attendants sleep on bedrolls laid out to the side of his; if he experienced tremors or shivers, as sometimes he did, they’d be expected to embrace him until the shaking stopped. Now he planned to have Manu share the same mattress. Perfection would be achieved if the old man and the young woman wore the fewest possible garments, preferably none, and neither one felt the slightest sexual stirring.

A perfect brahmachari, he later wrote in a letter, should be “capable of lying naked with naked women, however beautiful they may be, without being in any manner whatsoever sexually aroused.” Such a man would be completely free from anger and malice.

Sexlessness was the ideal for which he was striving. His relation to Manu, he told her, would be essentially that of a mother.

None of this would go on in secret; other members of his entourage might share the same veranda or room.

What’s important here is less Gandhi’s belief in the spiritual power to be derived from perfect, serene celibacy than the relation of his striving for self-purification to his lonely mission in Noakhali. Where could the real motivation be located, in his gnawing sense of failure for which a ratcheting up of his brahmacharya might provide healing, or in his need for a human connection, if not the intimacy he’d long since forsworn? There’s no obvious answer, except to say the struggle was at the core of his being and that it had never been more anguishing than it was in Srirampur. The two most conspicuous elements of his life there—the mission

and the spiritual striving—are usually treated as separate matters. But, here again, they were happening simultaneously, crowding in on each other: in Gandhi’s own mind, inextricably connected to the point of being one and the same.

The immediate effect of his summons to Manu was a cascading emotional crisis in his own inner circle, all taking place in the obscurity and shade of mostly Muslim Srirampur but soon seeping into public view. Plainly, the starting point was within Gandhi himself, in his sense that doctrine and mission were failing. “

I don’t want to return from Bengal defeated,” he remarked to a friend a few days after the summons to Manu. “I would rather die, if need be, at the hands of an assassin. But I do not want to court it, much less wish it.”

He’d cleared the decks for her arrival by dispatching his closest associates—notably Pyarelal, his secretary, and Pyarelal’s sister, Dr.

Sushila Nayar—to workstations in other villages. Sushila had previously played the part for which Manu was now being recruited. Back in 1938, Gandhi had tried out a young Jewish woman from Palestine named Hannah Lazar, a niece of

Hermann Kallenbach’s, who’d trained in massage. “

Of course she knows her art,” he wrote to her uncle in Johannesburg. “But she can’t all of a sudden equal the touch of Sushila who is a competent doctor and who learned massage especially for treating me.” Here Gandhi sounds more like a discriminating pasha with a harem than the ascetic he genuinely was.

Now, more than eight years after this letter and just six days after his summons to Manu, Gandhi told Sushila that it would remain her duty to stay in her village—in other words, that she’d not be included on his walking tour, because Manu would be taking care of his most personal needs. Nirmal Bose, who was standing just outside, heard “

a deeply anguished cry proceeding from the main room … [followed by] two large slaps given on someone’s body. The cry then sank down into a heavy sob.” When Bose got to the doorway, both Gandhi and Sushila were “bathed in tears.” The cries and heavy sob had been the Mahatma’s, he realized. Three days later, while bathing Gandhi for what appears to have been the last time, Bose summoned the courage to ask him whether he’d slapped Sushila. “Gandhiji’s face wore a sad smile,” Bose wrote in his memoir, “and he said, ‘No, I did not beat her. I beat my own forehead.’ ” That same evening, on December 20, 1946, with Manu beside him in his bed for the first time, Gandhi began his supposed yajna, or self-sacrifice, sometimes termed an “experiment” by him.

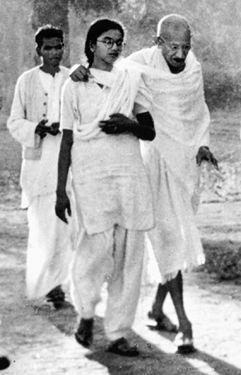

With Manu, his “walking stick

”

(photo credit i11.5)

“

Stick to your word,” he wrote in a note to Manu that day. “Don’t hide even a single thought from me … Have it engraved in your heart that whatever I ask or say will be solely for your good.”

Within ten days, Gandhi’s stenographer, a young South Indian named Parsuram, quit in protest over his revered leader’s nightly cuddle with Manu, which he couldn’t fail to have witnessed. Instead of questioning Gandhi’s explanation of its spiritual purpose, he registered a political complaint—that the inevitable reports and gossip would alienate public opinion. His argument didn’t impress the Mahatma. “

I like your frankness and boldness,” he wrote to the young man after reading his ten-page letter of resignation. “You are at liberty to publish whatever wrong you have noticed in me and my surroundings.” Later he scolded Bose for glossing over in his Bengali interpretation his attempt at one of his prayer meetings to offer a frank public account of the latest test he’d set for himself.

Pyarelal was also drawn into this emotional maelstrom, and not simply because he was partial to his sister. He’d had a crush on Manu himself. Gandhi now promised to keep his secretary at a distance if Manu

“does not want even to see him.” He could testify to his aide’s good character. “Pyarelal’s eyes are clean,” he wrote to Manu’s father a week before she was scheduled to reach Noakhali, “and he is not likely to force himself on anybody.” Gandhi then writes to Pyarelal urging him to keep his distance. “

I can see that you will not be able to have Manu as a wife,” says the revered figure who is now bedding down next to her on a nightly basis. Self-purification, it was already clear, could not be attempted in this world without complications.

Nirmal Bose, the detached Calcutta intellectual serving as Gandhi’s Bengali interpreter, wasn’t initially judgmental about Gandhi’s reliance on Manu. But his allegiance was gradually strained as he observed Gandhi’s manipulative way of managing the emotional ripples that ran through his entourage at a moment of national and personal crisis. He felt the Mahatma, in his preoccupation with the feelings of Pyarelal and his sister, was allowing himself to get distracted. “

After a life of prolonged brahmacharya,” Bose wrote in his diary, “he has become incapable of understanding the problems of love or sex as they exist in the common human plane.” So Bose took it upon himself, in conversation and several long letters over the next three months, to acquaint his master with the psychoanalytic concepts of the subconscious, neurosis, and repression. Gandhi jumped on a single passing reference to Freud in one of Bose’s letters.

He’d read Havelock Ellis and Bertrand Russell on sex but not Freud. It was only the second time, he wrote back, that he’d heard the name. “

What is Freudian philosophy?” asked the Mahatma, ever curious. “I have not read any writing of his.”

Bose’s basic point was made more bluntly in his diary and a letter to a friend than in his correspondence with the Mahatma. It was that Gandhi had allowed himself to use his bedmates as instruments in an experiment undertaken for his own sake and that he thus risked leaving “a mark of injury on personalities of others who are not of the same moral stature … and for whom sharing in Gandhiji’s experiment is no spiritual necessity.” He thought Manu might be an exception but wasn’t sure. Despite his restraint, Gandhi got the point. “

I do hope you will acquit me of having any lustful designs upon women or girls who have been naked with me,” he wrote back. That was the one count on which the Freudian in Bose felt certain of Gandhi’s innocence.

Feeling himself to have been distanced by his own frankness, Bose came to doubt he could be of much further use to Gandhi. Finally he asked to be relieved of his duties. In a valedictory letter, he said he saw signs that the Mahatma had, in fact, begun to attain the level of concentrated

personal force for which he’d been reaching in these months: “

I saw your strength come back in flashes when you rose to heights no one else has reached in our national life.”

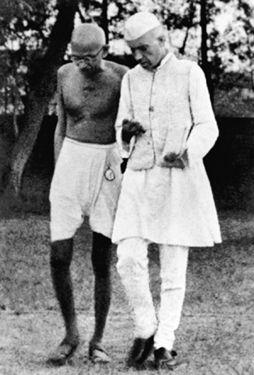

A week after Gandhi established his grandniece Manu in his household and bed, the urgency and weight of the constitutional crisis in New Delhi descended on the remote village of Srirampur, brought there on a visit of two and a half days by Nehru, now head of an “interim government” still subject to the British viceroy, and Nehru’s successor as Congress president,

J. B. Kripalani, a follower of Gandhi’s for three decades.

Given that the Congress president’s wife, Sucheta, had shared the Mahatma’s bed with him and Manu on one recent night, there was no need for Gandhi to brief his visitors on the yajna he’d just undertaken.

According to one account, Nehru himself came to the doorway of the room where Gandhi and Manu slept on his first night in Srirampur; having looked in, he silently stepped away. The sketchy account does not record whether he raised his eyebrows or shook his head.

In the following month, Gandhi would seek to explain his quest to both men in letters. Neither wanted to sit in judgment on the Mahatma. “

I can never be disillusioned about you unless I find the marks of insanity and depravity in you,” Kripalani replied. “I do not find such marks.” Nehru was even more reticent. “

I feel a little out of my depth and I hate discussing personal and private matters,” he wrote to a mentor he revered but frequently found perplexing, even troublesome.

Gandhi had first singled Nehru out as a Congress leader in 1928 and, while acknowledging conspicuous differences in outlook, had been openly calling him “my heir and successor” since 1934 when he made a show of giving up his own Congress membership. “

Jawaharlal is the only man with the drive to take my place,” he remarked five years later. For all his doting on Nehru, this was a practical political judgment based on two obvious factors—Nehru’s demonstrated mass appeal and tendency in a crisis to bend to the Mahatma’s view. He knew

his heir would never score high on any checklist of Gandhian values, that the younger man, more a Fabian than a Gandhian, could be expected to promote state planning and nationalized industries over the sort of village-level reconstruction he’d always advocated, that there was little question in his mind about the need for a modern military establishment in a future Indian state. But he waved aside such contradictions, treating them as matters of emphasis. “

He says what is uppermost in his mind,” Gandhi

observed in 1938, in a comment as revealing of himself as it was of Nehru, “but he always does what I want. When I am gone he will do what I am doing now. Then he will speak my language.”