Haiti After the Earthquake (37 page)

Read Haiti After the Earthquake Online

Authors: Paul Farmer

Dr. Dubique Kobel providing primary care services in Parc Jean-Marie Vincent, where 50,000 people were living in February 2010

Dr. Evan Lyon with patient at the General Hospital

Children in Parc Jean-Marie Vincent, March 2010; 1.3 million were living in similar conditions throughout the quake zone

Didi Bertrand Farmer speaking with a woman in camp Carradeux (3,500 people, 680 families, 1 water source, 7 latrines), July 2010

Naomi Rosenberg from Partners In Health's Right to Health Care Program with quake-affected patients, Philadelphia, March 2010

Shelove Julmiste in rehabilitation, Hôpital Albert Schweitzer

Loune Viaud and baby Rose at Zanmi Beni. (“I have a dream for every one of them.”)

The caregivers and children at Zanmi Beni, November 2010

Dr. David Walton at the Mirebalais hospital construction site, January 2011

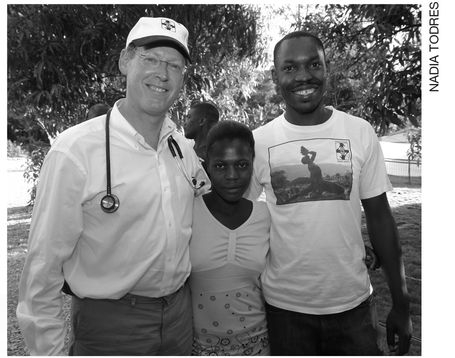

Dr. Paul and Dr. Christophe with Roseleine after treatment, Lascahobas, January 2011

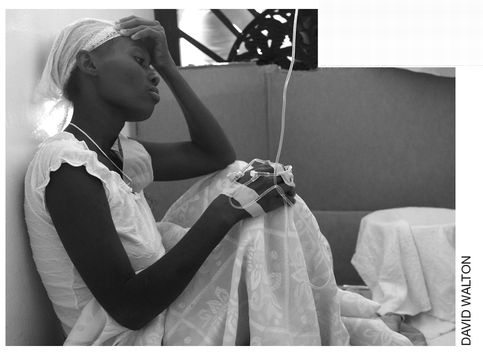

A cholera patient receiving intravenous fluids, Lascahobas

8.

LOOKING FORWARD WHILE LOOKING BACK

Lessons from Rwanda

T

o advance a process

of discernment is one of the only reasons to publish a book like this one, written as events continue to unfold. It's difficult amid such suffering to find hopeful and relevant examples of building back better. But Rwanda offers more than a glimmer of hope, and we have more years of perspective with which to render judgments about central Africa. The legacies of colonialism and failed humanitarianism are still evident there as they are in Haiti.

1

When Philip Gourevitch (following Linda Polman, Fiona Terry, and others

2

) asks us to consider “how, in the mid-nineties, fugitive Rwandan

génocidaires

were succored in the same way by international humanitarians in border camps in eastern Congo, so that they have been able to continue their campaigns of extermination and rape to this day,”

3

he is making a claim of causality regarding the disastrous consequences of a series of decisions made far from the scenes of suffering witnessed in the Congo.

4

Crossing the Rwanda-Congo border to Goma offers a lesson in contrasts: On one side of the frontier are Rwandan resettlement towns and planned villages, called

imidugudu

. On the other side, many of Goma's buildings are partly

buried in the hardened lava that poured forth from the giant Nyiragongo volcano in 1977 and again, more apocalyptically, in 2002. The Congolese side remains vulnerable to the raids of armed bands comprised of some of the same people who fled these camps when Rwandan forces finally invaded in 1996. This is the wild, wild east of Congo: almost as crowded as Rwanda, straddling the same volcanic hills, but immeasurably more lawless.

o advance a process

of discernment is one of the only reasons to publish a book like this one, written as events continue to unfold. It's difficult amid such suffering to find hopeful and relevant examples of building back better. But Rwanda offers more than a glimmer of hope, and we have more years of perspective with which to render judgments about central Africa. The legacies of colonialism and failed humanitarianism are still evident there as they are in Haiti.

1

When Philip Gourevitch (following Linda Polman, Fiona Terry, and others

2

) asks us to consider “how, in the mid-nineties, fugitive Rwandan

génocidaires

were succored in the same way by international humanitarians in border camps in eastern Congo, so that they have been able to continue their campaigns of extermination and rape to this day,”

3

he is making a claim of causality regarding the disastrous consequences of a series of decisions made far from the scenes of suffering witnessed in the Congo.

4

Crossing the Rwanda-Congo border to Goma offers a lesson in contrasts: On one side of the frontier are Rwandan resettlement towns and planned villages, called

imidugudu

. On the other side, many of Goma's buildings are partly

buried in the hardened lava that poured forth from the giant Nyiragongo volcano in 1977 and again, more apocalyptically, in 2002. The Congolese side remains vulnerable to the raids of armed bands comprised of some of the same people who fled these camps when Rwandan forces finally invaded in 1996. This is the wild, wild east of Congo: almost as crowded as Rwanda, straddling the same volcanic hills, but immeasurably more lawless.

What makes the difference? One answer is circular: the Rwandan side of the border has more security. Other assessments note a heavy Rwandan hand in recent extractive endeavors in the Congo. Another reason, and one with more lessons for Haiti, is a rationally planned development strategy directed by the Rwandan government. Rwanda remains a political flashpoint in international circles, generating almost as many discrepant views as Haiti. But its renaissance is increasingly recognized as an example of building back better. In 1996, two years after the genocide, Rwanda was still strewn with mass graves. With a million dead and two million recently repatriated refugees, it still ranked among the poorest countries in the world.

5

Although Kigali's infrastructure escaped major damage during the civil war and genocide, it was then a small city without the capacity to welcome even a fraction of the returnees. Many development experts were happy to write off Rwanda as a lost cause: the next in a long line of failed states doomed to ongoing conflict and underdevelopment.

5

Although Kigali's infrastructure escaped major damage during the civil war and genocide, it was then a small city without the capacity to welcome even a fraction of the returnees. Many development experts were happy to write off Rwanda as a lost cause: the next in a long line of failed states doomed to ongoing conflict and underdevelopment.

Fifteen years later, Rwanda has been transformed. If, as Jared Diamond has suggested, the collapse of Haiti and Rwanda were rooted in desperate competition for scarce resources, it's worth noting that Rwanda by 2000 was no less crowded and cramped than before the genocide.

6

But the strife within its borders had lessened even before the wheels of economic growth started turning. I'd like to consider some of the policies that may have led to this upward trajectoryâsome of them surely relevant to Haiti's own rebuilding challenges.

6

But the strife within its borders had lessened even before the wheels of economic growth started turning. I'd like to consider some of the policies that may have led to this upward trajectoryâsome of them surely relevant to Haiti's own rebuilding challenges.

Other books

Under Dark Sky Law by Tamara Boyens

Raistlin, mago guerrero by Margaret Weis

Out Late with Friends and Regrets by Egerton, Suzanne

Sky's Dark Labyrinth by Stuart Clark

El reino de las sombras by Nick Drake

Leave It to Cleavage by Wendy Wax

Backstabber (The Big Bang Series (behind the scenes bonus material)) by Starke, Stella

Claiming His Brother's Baby by Helen Lacey

Unmanned by Lois Greiman

The Kissing Deadline by Emily Evans