Halloween Candy (2 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

When someone in the nearby village was near death, the Maiden’s lover would appear at their doorway and seek entrance, as if trying to find his way back to his soul, which had remained on the other side. 10

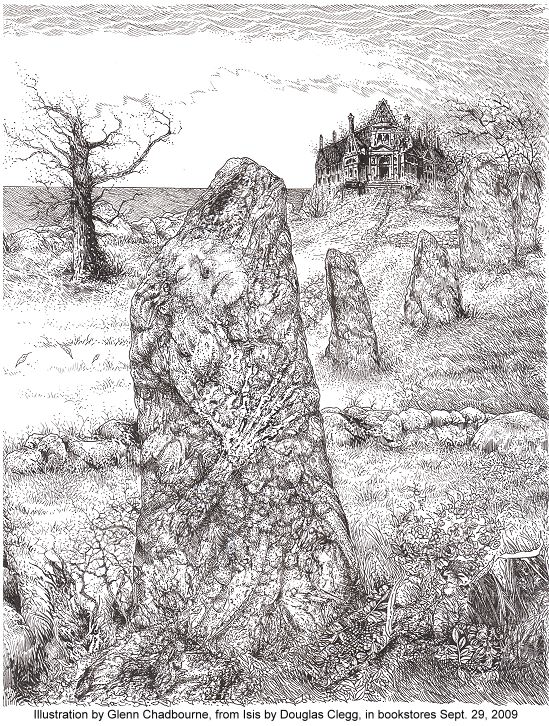

There was also a large round granite stone in the field at the edge of the sunken garden, not ten paces from the Tombs. Called the Laughing Maiden, it was believed that once in early times of the Christians, another maiden went out and laughed at the priest on Sabbath day and was turned to stone there.

I went to this stone as a girl with our gardener, who believed all the old tales. Old Marsh was thought of as the local color—the crackpot oldwives-tale man of the earth who believed all the old stories and would walk backward around a graveyard to avoid upsetting the dead. He had been known to plant sheep-nettle at the stables when one of the horses had gotten sick, “to keep out bewitchments,” he’d say quite proudly. He knew a story for every stone, every fountain, every plant, and every tree at Belerion Hall. Old Marsh took it all seriously, and he warned me against upsetting spirits by changing the old gardens too much. “They like their flowers as they like them,” he said when I had been uprooting the weed-like milk thistle. “Bad luck to do that, for the saying goes, ‘Set free the thistle and hear the devil whistle.’”

At the Tombs, he gave me the most serious advice. “Never go in, miss. Never say a prayer at its door. If you are angry, do not seek revenge by the Laughing Maiden stone, or at the threshold of the Tombs. There be those who listen for oaths and vows, and them that takes it quite to heart. What may be said in innocence and ire becomes flesh and blood should it be uttered in such places.”

I looked upon the rock chamber with its small double doorways and its chains and lock, a ruins more than a mausoleum, sunken into the grassy earth with a view of the wide gray sea beyond it, and remembered such stories.

I did not intend ever to cross its threshold.

11

12

Take Action Now --Isis Awaits

Get the Book

-Read the ultimate Halloween tale of the year, with unforgettable illustrations by Glenn Chadbourne.

Watch the Book Trailer

-but don't give away the secret within it.

Play the Isis Game

-more than 1.4 million people have played it.

Get the Isis Widget

-Blog it, Myspace it, Facebook it, enjoy it.

Download the Isis Desktop Wallpaper

-pick your own COOL

illustration from the book to sit on your computer desktop - FREE.

Get your Isis Avatar

-Watch Isis fall, see Isis walk, learn about the undead soldiers…and choose your avatar.

13

"Where Flies Are Born"

Douglas Clegg

The train stopped suddenly, and Ellen sat there and watched her son fill in the coloring book with the three crayolas left to him: aquamarine, burnt sienna, and silver. She was doing this for him: she could put up with Frank and his tirades and possessiveness, but not when he tried to hurt Joey. No. She would make sure that Joey had a better life. Ellen turned to the crossword puzzle in the back of the magazine section to pass the time. She tried not to think of what they’d left behind. She was a patient woman, and so it didn’t annoy her that it was another hour before anyone told the passengers that it would be a three hour stop, or more.

Or more

, translating into six hours. Then her patience wore thin and Joey was whining. The problem with the train, it soon became apparent, was one which would require disembarking. The 14

town, if it could be called that, was a quarter mile ahead, and so they would be put up somewhere for the night. So this was to be their Great Escape. February third in a mountain town at thirty below. Frank would find them for sure; only a day’s journey from Springfield. Frank would hunt them down, as he’d done last time, and bring them back to his little castle and she would make it okay for another five years before she went crazy again and had to run.

No

. She would make sure he wouldn’t hurt Joey. She would kill him first. She would, with her bare hands, stop him from ever touching their son again.

Joey said, “Can’t we just stay on the train? It’s cold out there.”

“You’ll live,” she said, bringing out the overnight case and following in a line with the other passengers out of the car. They trudged along the snowy tracks to the short strip of junction, where each was directed to a different motel or private house.

“I wanted a motel,” she told the conductor. She and Joey were to be overnight guests of the Neesons’, a farm family. “This isn’t what I paid for,” she said, “it’s not what I expected at all.”

15

“You can sleep in the station, you like,” the man said, but she passed on that after looking around the filthy room with its greasy benches. “Anyway, the Neesons run a bed-and-breakfast, so you’ll do fine there.”

The Neesons arrived shortly in a four-wheel drive, looking just past the curve of middle age, tooth-rotted, with

country

indelibly sprayed across their grins and friendly winks. Mama Neeson, in her late fifties, spoke of the snow, of their warm house “where we’ll all be safe as kittens in a minute,” of the soup she’d been making. Papa Neeson was older (

old enough to be my father

, Ellen thought) and balder, eyes of a rodent, face of a baby-left-too-long-in-bathwater. Mama Neeson cooed over Joey, who was already asleep.

Damn you, Joey, for

abandoning me to Neeson-talk

. Papa Neeson spoke of the snowfall and the roads. Ellen said very little, other than to thank them for putting her up.

“Our pleasure,” Mama Neeson said, “the little ones will love the company.”

16

“You have children?” Ellen winced at her inflection. She didn’t

mean

it to sound as if Mama Neeson was too old to have what could be called “little ones.”

“Adopted, you could say,” Papa Neeson grumbled, “Mama, she loves kids, can’t get enough of them, you get the instinct, you see, the sniffs for babies and you got to have them whether your body gives ‘em up or not.”

Ellen, embarrassed for his wife, shifted uncomfortably in the seat. What a rude man. This was what Frank would be like, under the skin, talking about women and their “sniffs,” their “hankerings,” Poor Mama Neeson, a houseful of babies and

this man

.

“I have three little ones,” she said, “all under nine. How old’s yours?”

“Six.”

“He’s an angel. Papa, ain’t he just a little angel sent down from heaven?”

Papa Neeson glanced over to Joey, curled up in a ball against Ellen’s side, “don’t say much, do he?”

17

The landscape was white and black; Ellen watched for ice patches in the road, but they went over it all smoothly. Woods rose up suddenly, parting for an empty flat stretch of land. They drove down a fenced road, snow piled all the way to the top of the fenceposts. Then, as with a barn behind.

We better not be sleeping in the barn

.

Mama Neeson sighed, “hope they’re in bed. Put them to bed hours ago, but you know how they romp…”

“They love to romp,” Papa Neeson said.

The bed was large and she and Joey sank into it as soon as they had the door closed behind them. Ellen was too tired to think, and Joey was still dreaming. Sleep came quickly, and was black and white, full or snowdrifts. She awoke, thirsty, before dawn. She was half-asleep, but lifted her head towards the window: the sound of animals crunching in the snow outside. She looked out—had to open the window because of the frost on the pane. A hazy purple light brushed across the whiteness of the hills—the sun was somewhere rising beyond the treetops. A large brown bear sniffed along the porch rail. Bears should’ve frightened her, 18

but this one seemed friendly and stupid, as it lumbered along in the tugging snow, nostrils wiggling. Sniffing the air; Mama Neeson would be up—four thirty—frying bacon, flipping hotcakes on the griddle, buttering toast. Country mama. The little ones would rise from their quilts and trundle beds, ready to go out and milk cows or some such farm thing, and Papa Neeson would get out his shotgun to scare off the bear that came sniffing. She remembered Papa’s phrase: “the sniffs for babies,” and it gave her a discomforting thought about the bear.

She lay back on the bed, stroking Joey’s fine hair, with this thought in her mind of the bear sniffing for the babies, when she saw a housefly circle above her head; then, another, coming from some corner of the room, joining its mate. Three more arrived. Finally, she was restless to swat them. She got out of bed and went to her overnight bag for hairspray. This was her favorite method of disposing of houseflies. She shook the can, and then sprayed in the direction of the (count them: nine) fat black houseflies. They buzzed in curves of infinity. In a minute, they began dropping, one by one, to the rug. Ellen enjoyed taking her boots and slapping each fly into the next life. 19

Her dry throat and heavy bladder sent her out to the hallway. Feeling along the wall for the light switch or the door to the bathroom—

whichever came first. When she found the switch, she flicked it up, and a single unadorned bulb hummed into dull light.

A little girl stood at the end of the hall, too old for the diaper she wore; her stringy hair falling wildly almost to her feet; her skin bruised in several places—particularly around her mouth, which was swollen on the upper lip. In her small pudgy fingers was a length of thread. Ellen was so shocked by this sight that she could not say a word—the girl was only seven or so, and what her appearance indicated about the Neesons…

Papa Neeson was like Frank. Likes to beat people. Likes to beat

children. Joey and his black eyes, this girl and her bruised face. I could

kill them both.

The little girl’s eyes crinkled up as if she were about to cry, wrinkled her forehead and nose, parted her swollen lips. 20

From the black and white canyon of her mouth a fat green fly crawled the length of her lower lip, and then flew toward the light bulb above Ellen’s head.

Later, when the sun was up, and the snow outside her window was blinding, Ellen knew she must’ve been half-dreaming, or perhaps it was a trick that the children played—for she’d seen all of them, the two-yearold, the five-year-old, and the girl. The boys had trooped out from the shadows of the hall. All wearing the filthy diapers, all bruised from beatings or worse. The only difference with the two younger boys was they had not yet torn the thread that had been used to sew their mouths and eyes and ears and nostrils closed. Such child abuse was beyond imagining. Ellen had seen them only briefly, and afterwards wondered if perhaps she hadn’t

seen

wrong. But it was a dream, a very bad one, because the little girl had flicked the light off again. When Ellen reached to turn it back on, they had retreated into the shadows and the feeling of a surreal waking state came upon her.

The Neesons could not

possibly be this evil

. With the light on, and her vision readjusting from 21

the darkness, she saw only houseflies sweeping motes of dust through the heavy air.

At breakfast, Joey devoured his scrambled eggs like he hadn’t eaten in days; Ellen had to admit they tasted better than she’d had before. “You live close to the earth,” Papa Neeson said, “and it gives up its treasures.”

Joey said, “Eggs come from chickens.”

“Chickens come from eggs,” Papa Neeson laughed, “and eggs are the beginning of all life. But we all gather our life from the earth, boy. You city folks don’t feel it because you’re removed. Out here, well, we get it under our fingernails, birth, death, and what comes in between.”

“You’re something of a philosopher,” Ellen said, trying to hide her uneasiness. The image of the children still in her head, like a halfremembered dream. She was eager to get on her way, because that dream was beginning to seem more real. She had spent a half-hour in the shower trying to talk herself out of having seen the children and what had been done to them: then, ten minutes drying off, positive that she had seen what she’d seen. It was Frank’s legacy: he had taught her to 22

doubt what was right before her eyes. She wondered if Papa Neeson performed darker needlework on his babies.

“I’m a realist,” Papa Neeson said. His eyes were bright and kind—

it shocked her to look into them and think about what he might/might not have done.

Mama Neeson, sinking the last skillet into a washtub next to the stove, turned and said, “Papa just has a talent for making things work, Missus, for putting two and two together. That’s how he grows, and that’s how he gathers. Why if it weren’t for him, where would my children be?”

“Where are they?” Joey asked.

Ellen, after her dream slash hallucination slash mind-your-ownbusiness, was a bit apprehensive. She would be happy not to meet mama Neeson’s brood at all. “We have to get back to the train,” she said. “They said by eleven.”

Papa Neeson raised his eyebrows in an aside to his wife. “I saw some flies at the windows,” he said. “They been bad again.”