Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (14 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Tuthmosis’ hidden tomb, usually identified using the modern tomb-numbering convention as KV 38, was a relatively simple affair consisting of a rectangular antechamber, a pillared burial chamber and small storeroom linked together by a series of narrow passages and steep stairways. His associated mortuary chapel,

Khenmetankh

(literally ‘United with Life’), which was for a long time mis-identified as the shrine of Prince

Wadjmose, was situated a good hour's walk away from the Valley of the Kings, at a site later chosen for the mortuary temple of the 19th Dynasty King Ramesses II, now popularly known as the Ramesseum.

Tuthmosis had been a middle-aged man with a successful career behind him when he acceded to the throne and he had reigned for no more than ten to fifteen years before, aged about fifty, he ‘rested from life’. Fifty years may seem a short life-span to modern readers accustomed to seeing relations living well into their seventies and eighties, but it would have been an eminently reasonable age for an active Egyptian soldier to achieve; throughout the New Kingdom, life expectancy at birth was considerably lower than twenty years, while those who survived the perils of birth and infancy to reach fourteen years of age might then expect to live for another fifteen years. This compares well with the average life expectancies normally found in pre-industrial societies, which tend to vary between twenty and forty years, and with the suggested average life expectancy of a Roman senator at birth of thirty years.

4

Those élite Egyptian males, who able to maintain higher standards of hygiene and nutrition than the less fortunate artisans and peasants, who performed little or no dangerous manual work, who were not faced with the dangers of childbirth and could afford the best medical attention, benefited from a slightly increased life expectancy, but no one could look forward with any confidence to a long old age. Although the Egyptians were famed throughout the ancient world for their medical expertise, there was relatively little that any doctor could do to help when faced with a seriously ill or wounded patient, and the average age for tomb owners (that is, the male élite) of the Dynastic Period has been calculated at between thirty and forty-five years.

5

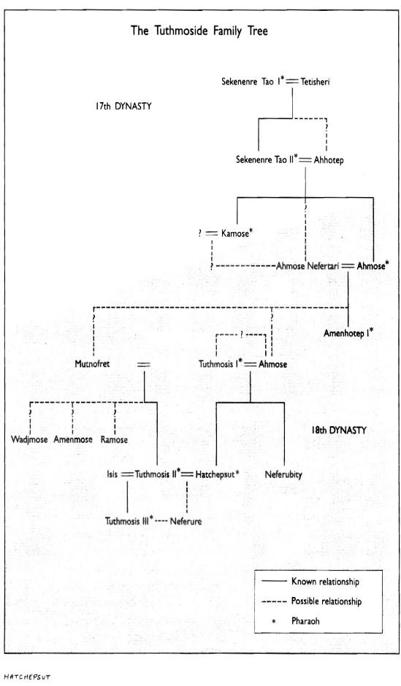

The high levels of infant and child mortality, combined with the low life expectancy, made it very difficult for the Egyptian royal family to maintain its exclusivity. In an ideal world, as we have already seen, the heir to the throne would be the son of the king and his consort who was usually herself a close blood relation, and often a half- or full sister of the king. The crown prince would, therefore, be of unblemished royal descent through both his father and his mother, and by marrying his sister he could maintain the tradition of family purity. However, no matter how many children were conceived by the royal couple, there could be no guarantee that any would live to become adults. Given the

lack of effective contraceptives and often-expressed desire for large numbers of offspring, we might expect to find the nuclear royal family expanding rapidly throughout the New Kingdom. This was not the case. Instead, the Tuthmoside royal family was plagued by a dearth of children, with sons being in particularly short supply and single daughters becoming the norm. Nor were they the only New Kingdom royal family to suffer from this problem; King Ramesses II, perhaps exceptionally unfortunate even by Egyptian standards, was eventually succeeded by Prince Merenptah, his thirteenth son born to one of his many secondary wives. Although the Egyptian king always had the back-up of his multiple wives and concubines, any of whom could in theory produce a legitimate king's son and heir, the succession of a lesser prince to the throne was not regarded as ideal.

There is some confusion over the number of children actually born to Tuthmosis I and his consort, Queen Ahmose. We know of two daughters, Princess Hatchepsut and her sister Princess Akhbetneferu (occasionally referred to as Neferubity) who died in infancy. We also have firm historical evidence that Tuthmosis I fathered two sons, the Princes Wadjmose and Amenmose, and possibly a third son, Prince Ramose.

6

Princes Amenmose and Wadjmose survived into their late teens but never acceded to the throne. As both boys had been raised in the tradition of royal princes, and as Amenmose in particular seems to have undertaken some of the duties of the heir to the throne, it appears that both were regarded as potential kings who failed to inherit only because they predeceased their father; both princes disappear before the death of Tuthmosis I. Wadjmose, the elder brother, is the more obscure. We know that he was taught by Itruri and possibly by Paheri, grandson of Ahmose, son of Ibana; he is depicted in the tomb of Paheri as a young boy sitting on his tutor's knee. He also appears in a prominent role in his father's badly damaged funerary chapel where a side-room served as a family shrine for the mortuary cults of various family members including the secondary Queen Mutnofret, the mysterious Prince Ramose and Prince Wadjmose himself.

Amenmose, the younger but possibly longer-lived son, was accorded the title of ‘Great Army Commander’, the role now traditionally allocated to the crown prince. Physical bravery had become an important New Kingdom royal attribute and Amenmose was clearly expected to enjoy the hearty lifestyle of the male élite. A broken stela tells us that,

during his father's regnal Year 4, Amenmose was already hunting wild animals in the Giza desert near the Great Sphinx, a favourite playground of the royal princes. Big-game hunting was by now a major prestige sport recently made infinitely more exciting by the use of the composite bow and the swift and highly mobile horse-drawn chariot which allowed the pursuit of fast-moving creatures such as lions and ostriches. Middle Kingdom hunting had been a far more staid affair, with the brave huntsman standing still to fire arrows at a pre-herded and occasionally penned group of ‘wild’ animals.

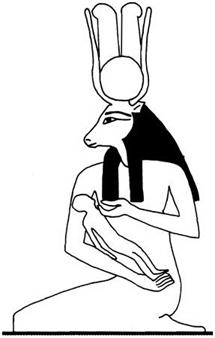

Fig. 3.1 The infant Hatchepsut being suckled by the goddess Hathor

Just how old could Amenmose have been when he was to be found chasing ostriches across the Giza desert? If Amenmose was the A son of Ahmose and Tuthmosis, if Ahmose was the sister or half-sister of Tuthmosis, and if we therefore assume that the royal siblings embarked upon their incestuous marriage only after Tuthmosis became king, Amenmose must have been barely four years old during his father's Year 4; surely a little too young for even the most precocious of princes to be found training with the army or hunting wild animals. This reasoning is, of course, full of ‘ifs’, and it is entirely possible that a relatively young prince could have played a purely honorary role in the life of the army; Ramesses II, for example, allowed all his sons to travel with the army, and the five-year-old Prince Khaemwaset is known to have accompanied a military campaign in Lower Nubia. However, the apparent discrepancy in ages strongly suggests that Amenmose and Wadjmose, and perhaps the ephemeral Ramose, may not in fact have been the children of Ahmose but of an earlier wife, possibly the mysterious Lady Mutnofret who features alongside Wadjmose in his father's funerary chapel.

We know very little about Lady Mutnofret, but it is obvious that she was a person of rank, perhaps even of royal blood, who was held in the highest honour. This is confirmed by an inscription at Karnak where a lady named Mutnofret is described as ‘King's Daughter’.

7

We have already seen that it is Mutnofret rather than Queen Ahmose who appears alongside Wadjmose and Ramose in the king's mortuary chapel; here her statue wears the royal uraeus and her name is written in a cartouche. Mutnofret is also known to have been the mother of Tuthmosis' eventual successor, Tuthmosis II. The Princes Amenmose, Wadjmose, Ramose, and Tuthmosis II may therefore have been full brothers, possibly born before their father married Ahmose. This tangle of relationships would make more sense if we had confirmation that Tuthmosis was a widower at his accession – highly likely, given that he is likely to have been at least thirty-five years old – his first wife Mutnofret having borne him several sons before dying.

Fig. 3.2 A hippopotamus hunter

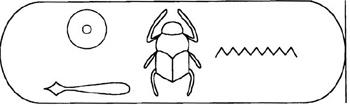

The Tuthmoside succession following the death of Tuthmosis I – the so-called ‘Hatchepsut Problem’ – is a subject which greatly perplexed late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century egyptologists, and the effects of their confusion still linger in some more recent publications. The names of the individual monarchs involved had been known for some time (Tuthmosis I, II and III, Hatchepsut), but the precise sequence of their reigns and their relationships with each other were not, although it was generally assumed that the three Tuthmoses followed each other in sequence with Hatchepsut appearing in some unknown capacity some time after Tuthmosis II. Unfortunately, the monumental evidence which might have been expected to help solve the mystery had been tampered with at some point in antiquity, the original cartouches

8

being re-cut to give the names of other pharaohs

Fig. 3.3 The cartouche of King Tuthmosis II

involved in the succession muddle. This deliberate defacement of the royal monuments was generally accepted as evidence of intense personal hatreds stemming from a desperate struggle for power within the royal family.

In 1896, the German egyptologist Kurt Sethe, basing his conclusions on a meticulous study of the erased cartouches, and on the erroneous assumption that the defaced cartouches must have been re-carved by the monarch whose name replaced the original, suggested that the succession of monarchs must have been as follows:

9

1 Tuthmosis I. Deposed by –

2 Tuthmosis III

3 Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III co-regents, Hatchepsut the senior king. Hatchepsut deposed by –

4 Tuthmosis III

5 Tuthmosis II and Tuthmosis I co-regents, until the death of Tuthmosis I