Hervey 08 - Company Of Spears (2 page)

Read Hervey 08 - Company Of Spears Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

THE N

IZAM’S DAUG

HTERS

1816: in India Matthew Hervey fights to prevent bloody civil war.

‘

Captain Hervey of the 6th Light Dragoons and ADC to the Duke

of Wellington is back in the saddle … He is as fascinating on

horseback as Jack Aubrey is on the quarterdeck

’

THE TIMES

A RE

GIMENTAL AFF

AIR

1817: Matthew Hervey faces renegades at home and in North America.

A riveting tale of heroism, derring-do and enormous resource in the

face of overwhelming adversity

’

BIRMINGHAM POST

A

CALL TO ARM

S

1819: Matthew Hervey races to confront Burmese rebels massing in the jungle.

‘

Hervey continues to grow in stature as an engaging and credible

character, while Mallinson himself continues to delight

’

OBSERVER

TH

E SABRE’S ED

GE

1824: in India Matthew Hervey lays siege to the fortress of Bhurtpore.

‘

Splendid… the tale is as historically stimulating

as it is stirringly exciting

’

SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

RU

MOURS OF W

AR

1826: while Matthew Hervey prepares for civil war in Portugal, he

remembers the Retreat to Corunna twenty years previously.

‘

I enjoyed the adventure immensely … as compelling, vivid and

plausible as any war novel I’ve ever read’

ANDREW ROBERTS

,

DAILY TELEGRAPH

AN

ACT OF COUR

AGE

1826: a prisoner of the Spanish, Matthew Hervey relives the blood

and carnage of the Siege of Badajoz.

‘

Concentrating on the battle of Talavera and the investment of

Badajoz, both sparklingly described, [Mallinson]plays to his

undoubted strengths

’

OBSERVER

CO

MPANY OF SPE

ARS

1827: on the plains of South Africa, Matthew Hervey

confronts the savage Zulu.

A damn fine rip-roaring read

’

LITERARY REVIEW

FOREWORD

The historian Correlli Barnett (

Britain and Her Army

) describes how ‘thanks to their mercenary army’ Britain as a whole ‘would never feel the burden of world power in the Victorian age … The British could rage at military incompetence when the army they neglected (and never joined) suffered some disaster … they could presume to take pride in victories won despite their indifference. War became a noise far away.’

Matthew Hervey and the 6th Light Dragoons knew about noise far away: they had heard it well enough in India. But they also knew there could be noise at home – if not actual war then certainly something as repugnant, for in 1827 the Metropolitan Police Act was still two years off, and the magistrates’ only recourse was to the army when civil disturbance threatened.

There was Ireland too, restive in its condition of exploitative poverty and discriminatory legislation. Britons were divided over the Catholic question – giving Catholics the vote and removing the obstacles to holding public office – ‘Catholic Emancipation’. There were no riots against Emancipation yet, as there had been the century before; but there was suspicion, and the authorities had no certain idea where it would lead. There was, indeed, ‘noise’ enough to disturb a good night’s sleep from time to time, if not so much as to keep the country awake for too long.

So Matthew Hervey, thirty-six years old, and in the midst of that glorious metamorphosis from a regimental to a commanding officer, finds himself in noisy circumstances once again. And, naturally, he meets those who would put fingers in their ears rather than deal with the noise. For this is an age when change, change in the army, is regarded as unnecessary, perhaps even injurious to those regimental qualities that had assured victory at Waterloo: discipline, personal bravery and boldness in combat.

Meanwhile, in Prussia, a major general not very much older than Hervey – Carl von Clausewitz – who had fought the French that day in 1815, is putting the final touches to his penetrating study of war and its practice, so that if a Prussian army were again required to do its Kaiser’s will it would do so with absolute efficiency. And at the other end of the technological spectrum, in southern Africa, an instinctive soldier, Shaka, King of the Zulu, is consolidating his astonishing military successes; for in truth Shaka and Clausewitz speak the same military language.

It is these old questions and new threats that Matthew Hervey and the 6th Light Dragoons face, and whose new lessons and old truths they will have to learn and re-learn – painfully.

Allan Mallinson

July 2005

Rebuke the company of spearmen…

scatter thou the people that delight in war.

PSALM 68

PART I

PATHS OF GLORY

England

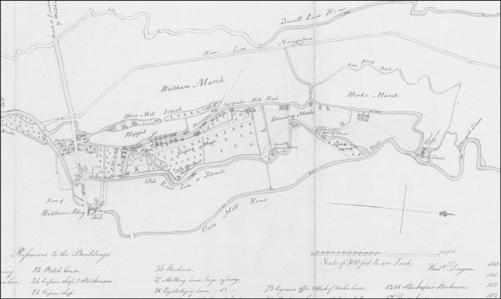

Plan of the Royal Gunpowder Manufactory at Waltham Abbey in 1830 by Frederick Drayson from his

A Treatise on Gunpowder.

The National Archive, ref. MFII 15/31

MANOEUVRES

Hounslow Heath, 12 March 1827

Acting-Major Matthew Hervey nodded to the adjutant, and in as many seconds only as it took for him, the officer in temporary command of the 6th Light Dragoons, to rein round to face front again, the first section of the Chestnut Troop discharged a thunderous salvo. Gilbert, his battle-charger, and at rising fifteen years a seasoned campaigner, threw up his head but did not move a foot. Hervey let out the reins a little so that the iron grey gelding could play with the bit as reward.

He looked over his left shoulder, then his right. The lines were ragged. Troop horses had leapt forward, some had run back, others had reared and turned. Barely half the regiment stood as they had been dressed. Even his trumpeter’s grey, a mare which should have known better, was showing a flank and bucking hard, determined to unseat her rider.

Hervey nodded again, the adjutant raised his arm, and the Chestnuts’ second section fired. As the smoke cleared, he could see the first section’s men standing ready, guns reloaded, and second section’s beginning the thirty fevered seconds of swabbing, ramming and tamping before the number one could shout ‘On!’ to tell his section officer that the gun was shotted and re-laid on its target.

Except that there was no shot or target. The Chestnut (more properly the

First

) Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, fired blank this morning. They did so to accustom the remounts – and recruits – of the 6th Light Dragoons to the noise of battle. It was not much by way of comparison with the real thing, Hervey knew (

by God,

how he knew!), but it was a good deal better than nothing; and certainly a good deal better than the usual method, the band’s banging and crashing on the square. It was decent of the Chestnuts to oblige them thus, although the Sixth had paid for the powder; and in any case, Hervey thought there must be gain for the Chestnuts too, for there was nothing like the thrill of real powder instead of ‘dry’ drills on the parade ground – even if the gun jumped back not a fraction of what it would when shotted and full-charged. He would have each of them fire in turn now, six nine-pounders, to test the nerve of the horses which had been half petrified into docility by the two salvos. He nodded to the adjutant a third time.

Number one gun fired, and the remaining rooks in the distant elms took flight, so that Hervey imagined there was not a bird perched on any branch on Hounslow Heath.

‘Rugged elms,’ he mused. He liked elms. As a boy he had climbed them, about the churchyard in Horningsham, to test his courage or to see what the tall nests held. Or sometimes on the plain to gain a distant prospect. He loved the elm-lined lanes in high summer, dark leafy tunnels where he might catch sight of a roe deer at midday – still, secret places, a foreign land, far from the safe parsonage and yet within sound of the church bell. There were no elms in foreign lands, though. Or if there were, they were poor specimens: he had seen none he could recall in France, or Belgium, none in the forests of the east – India, Ava – and certainly not in Spain and Portugal. Yet there

must

have been … but not the ‘rugged elm’. He thought of his Wiltshire churchyard again, ‘where heaves the turf in many a mould’ring heap’; beneath the tall elms, where ‘the rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep’. Yes, the elm had a power to command attention, more so even than the oak. Elms were England’s leafy witnesses – to village-Hampdens, mute inglorious Miltons and guiltless Cromwells, as well as to the great men themselves. What was it in that poem that could conjure a vision of his youth – his simpler, honest,

chaste

youth? Was it true that General Wolfe (as brave as any man to wear the King’s uniform) had said before battle that he would rather have composed Gray’s

Elegy written in a Country Churchyard

than take Quebec? Hervey did not suppose that Wolfe had meant it to be taken exactly literally, if he had said it at all; nevertheless there lay power in those words, power to invoke a visceral love of country. Was it not time for him, now, to return to the elms of Horningsham, to ‘the blazing hearth’, and to his makings? The question was point-less: behind him, albeit under his

temporary

orders, was his regiment –

his

regiment! This was what he had dreamed of for long years. There could never be a going back. Not, surely, without diminution? But was that not to pit himself against Gray’s own injunction: ‘Let not ambition mock their useful toil’? He must not allow himself conceit in this temporary command: