Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (26 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

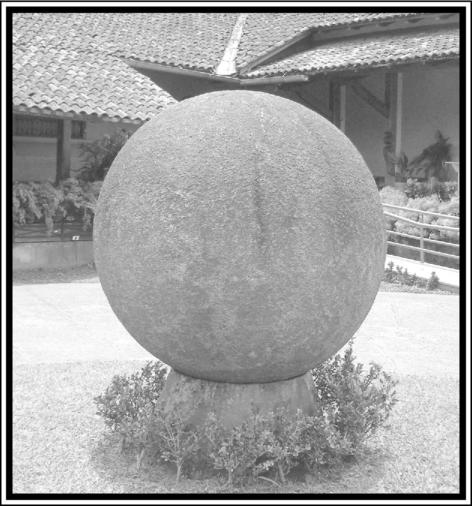

Photograph by Connor Lee. (GNU Free Documentation License).

Stone sphere in the courtyard of El Musco Nacional.

One of the most enigmatic puzzles

of pre-Columbian America is that of

the mysterious stone spheres of Costa

Rica. Hundreds of these stone balls,

varying in size from a few centimeters

to 7 feet in diameter and the largest

weighing 16 tons, have been found in

the Diquis region near the towns of

Palmar Sur and Palmar Norte, close

to the Pacific coast of southern Costa

Rica. The majority are fashioned from

granodiorite, a hard, igneous rock

similar to granite, but there are a few

examples made of coquina, a type of

limestone composed mostly of shells

and shell fragments.

The spheres first came to light in

the 1930s, when the United Fruit Company was clearing jungle to plant banana and other fruit trees. Workers for

the company discovered the objects

and, remembering a local legend about

the spheres being built around a core

of gold, blew many of them apart with dynamite looking for the hidden gold.

In 1948, Dr. Samuel Lothrop of the

Peabody Museum at Harvard University, and his wife, studied the stone

balls in context, and in 1963 the final

report of the study was published. In

his report, Lothrop records a total of

186 examples, although he had also

heard of a site near Jalaca that had

another 45 balls, before they were

taken away to other locations. There

have also been finds on Cano Island,

12.5 miles west of the southern Pacific

coast. On this evidence it seems that

there were once several hundred of

these stone sculptures in existence.

Since the 1940s, most of the balls have

been removed from their original context, often being transported by rail all

over the country. Today, only six are

known to remain in their original positions. Some can be seen displayed in

the National Museum, and several are

in parks and gardens in the country's

capital, San Jose.

Scholarly research into the Costa

Rica stone spheres has been going on

for more than 60 years. It began in 1943

with a study of the objects by archaeologist Doris Zemurray Stone, daughter of Samuel Zemurray, founder of the

United Fruit Company. She examined

the stones directly after they were discovered by workers for the Fruit Company. Stone, later to become the

director of the National Museum of

Costa Rica, published her findings in

the journal American Antiquity in 1943.

The study contains plans of five sites,

including 44 stone balls, and her interpretation was that the spheres

could have served as cult images or

cemetery markers, or were perhaps

connected with some kind of calendar.

The publication of the Lothrops' study

in 1963 includes maps of sites where

the spheres were found, and comprehensive accounts of pottery and metal

artifacts found in association with

and in the vicinity of them. Also included are numerous photographs and

drawings of the spheres, including

measurements and notes on their

alignments.

Further archaeological excavations in the 1950s found the stone

spheres associated with pottery and

other artifacts known from the preColumbian cultures of southern Costa

Rica. There have been various other

studies made since then, the most thorough being that of archaeologist

Ifigenia Quintanilla of the National

Museum of Costa Rica, from 1990 to

1995. Archaeologists have long puzzled

over the origin of these strange

spheres, and whether they were natural or man-made is still a much discussed point. Some geologists have

suggested that the stones were formed

naturally, theorizing that after a volcano released magma into the air, it

settled in a hot, ash-filled valley; the

blobs of magma then gradually cooled

down to form spheres. Another suggestion is that the original granite

blocks were positioned in a man-made

pit at the bottom of a powerful waterfall, and the effect of the water continuously flowing over them slowly

modeled the stones into near-perfect

spheres. Despite these theories, it is

more probable that the stones are manmade, especially in view of the fact

that the granodiorite from which the

majority of them were created does

not occur naturally in the area. The

quarry from which the rock originated is located in the Talamanca mountain

range, about 50 miles from the area

where the balls have been found. Archaeologist Ifigenia Quintanilla carried out fieldwork in the area of the

finds from 1990 to 1995 and traced the

source of the raw material, as well as

some boulders that were possibly unfinished examples of the stone

spheres. Quintanilla's excavations also

revealed flakes from the balls that indicate how they were made. Her findings suggest that the most plausible

method would have been to begin by

reducing a roughly circular boulder to

a more spherical shape by alternative

heating and cooling to fracture the

rock. The builders could then have

smoothed them out using hard stone

hammers, possibly of the same material, and finally polished them using

other stone tools.

One misconception about the objects is that they are almost perfect

spheres, accurate to within "0.5 inch

or 0.2 percent" as some have suggested.

This is not the case, as there have been

no such precise measurements of the

spheres. The balls are not flawlessly

smooth at all, some can differ more than

5 centimeters in diameter from a true

sphere. A problem of a different type

is how pre-Columbian societies moved

the stones to their required locations.

Such a task certainly points to an advanced and organized culture (though

if the stones were carved in a mountain quarry, it is obvious that spherical objects roll fairly easily, especially

downhill).

The question of who made these

mysterious spheres and why is a more

complicated issue. According to archaeologists the spheres were shaped

during two separate cultural periods.

Only a handful of spheres remain from

the earlier of these, known as the

Aguas Buenas period, which lasted

from around A.D. 100 to 500. In the second phase, the Chiriqui period (which

dates from around A.D. 800 to 1500), a

larger amount of the stone spheres

appear to have been manufactured,

with a distribution along the lower

part of the Terraba River. However,

this does not tell us anything about the

function of the spheres. Leaving aside

helpful intervention by extraterrestrials or Atlanteans, the most unique

theory is that they were set up by an

extremely advanced prehistoric culture to function as antennae-forming

part of an ancient worldwide power

grid. However, without concrete evidence, such a theory is baseless, and

just as mythical as the local legend that

the local people had access to a potion

with which they were able to soften

the rock. In their 1998 book, Atlantis

in America: Navigators of the Ancient

World, Ivar Zapp and George Erikson

suggest that the spheres were set up

as navigational instruments by an advanced ancient seafaring race, a race

that influenced the Greek philosopher

Plato to write about the lost land of

Atlantis. However, this theory requires

the spheres to be placed close enough

to the coast to be seen by navigators,

which is not the case. It also presupposes an accuracy in the alignments

of the spheres not present in the examples we have left in their original

context.

We don't really know why these

objects were made, especially as most

of them have been moved from their

original locations. This is a significant

problem, as the placements of the stone balls was probably of vital importance

to the people who first positioned

them. However, going on the available

evidence, the most probable theory for

a number of the spheres is that they

were used as markers of some kind,

perhaps property boundaries or status

symbols. Another idea, taking into account that many of the balls were originally found in alignments, is that they

represent the sun, moon, and all the

known planets at the time of their

placement. It has even been suggested

that they represent the entire solar

system. An interesting fact noted by

Lothrop in the 1940s was that several

of the balls he examined seemed to

have tumbled down from neighboring

mounds, which were formerly the sites

of houses. Perhaps the spheres had

once been contained inside these

structures on top of the mounds,

though this would make them ineffective for astronomy, and certainly of no

use to navigators. It is likely that the

spheres had numerous purposes,

which perhaps changed over the 1,000

years they were around. One interesting idea is that the laborious manufacture of the spheres may itself have

been a significant ritual as importantor perhaps more important-than the

finished product.

Ever since their discovery, the

stone spheres of Costa Rica have been

affected by exposure to temperature

changes, damage from rain and irrigation, and periodic burning. In 1997, the

Landmarks Foundation was created to

conserve sacred sites and landscapes

around the world. In 2001, with the

cooperation of various governmental

organizations, the Foundation and the

National Museum of Costa Rica were

able to transport many of the spheres

from San Jose across the high mountain range and back to their original

homes. They are currently being

stored and protected until a Cultural

Center can be constructed to house and

display them in their original locations

in the Diquis Delta.

Archaeologists still occasionally

find new examples of the spheres in

the mud of the Diquis Delta, and there

are probably more out there. In modern day Costa Rica, the stones can be

found in museums and adorning the

lawns outside various official buildings, hospitals, and schools. Two of

them have been transported to the

United States: one is on display in the

museum of the National Geographic

Society in Washington, D.C., while the

other is in a courtyard near the

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and

Ethnography at Harvard University in

Cambridge, Massachusetts. The

spheres can also be found decorating

the gardens of the homes of the rich,

where they are regarded as status symbols. In a way then, though many of the

stones have long ago been moved from

their place of origin, some of them at

least may be serving the purpose for

which they were originally intended.

Photograph by Y. Dondas

The coast of Crete, which was once patrolled by the bronze giant, Talos.

Many people are familiar with the

figure of Talos through his depiction

as a bronze giant in the 1963 movie

Jason and the Argonauts using Ray

Harryhausen's stunning special effects. But where did the idea for Talos

come from, and could he have been the

first robot in history?

Originally, Talos was a figure of

Cretan legend, though there are many

diverse myths to account for his origins. After Zeus kidnapped Europa

and took her to Crete, he gave her