Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (43 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

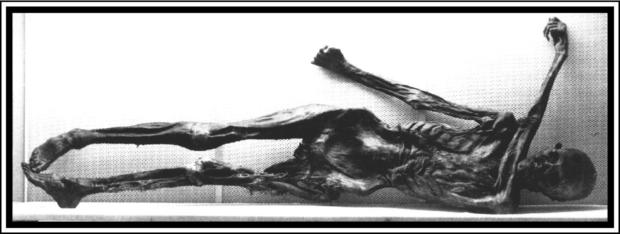

@ Innsbruck Medical University, W. Platzer.

Skeleton of the Ice Man at Innsbruck Medical University.

On a clear day in September 1991,

high in the desolate Otztal Alps, close

to the border between Italy and Austria, two German hikers (Helmut and

Erika Simon) made what has proven

to be one of the most incredible discoveries of the 20th century. Lying face

down in the ice was a frozen body.

Thinking they had found the remains

of a mountaineer who had died in a

fall, the couple informed the authorities, who arranged to visit the site the

following day. Due to the melting of

the glacier, it was not unusual to find

the bodies of climbers who had died in

accidents in the area. Three weeks

earlier, the mummified remains of a

man and woman who had set off hiking in 1934, never to be seen again, had

been discovered. The day after Helmut

and Erika Simon's discovery, the Austrian police arrived at the site and be

gan, somewhat clumsily, to remove the

body from its frozen grave. During its

extraction from the ice, some of the

body's clothing was shredded, a hole

was punched in the hip with a jackhammer, and its left arm was snapped

while attempting to force the body into

a coffin.

The body was transported to the

University of Innsbruck, where a careful examination revealed that it was

definitely not a modern mountaineer.

Radiocarbon dating showed that the

remains were of a man who had died

around 3200 B.C. (in the Late Neolithic

period) and was thus the oldest preserved human body ever discovered.

Further examinations of Otzi, as he

has become known (because he was

found in the Otztal Alps), followed, and

it was determined that he was 5-feet

2-inches tall and between 40 and 50 years of age when he died, although

the cause of death remained a mystery.

Analysis of his stomach contents revealed the remains of two meals, the

last eaten about eight hours before he

died and consisting of a piece of unleavened bread made of einkorn

wheat, some roots, and red deer meat.

Analysis of extremely well-preserved

pollen from the intestines revealed

that Otzi died in late spring or early

summer.

Otzi had a total of 57 tattoos on his

body, comprising small parallel stripes

and crosses, which were made with a

charcoal-based pigment. As the tattoos

were concentrated around the spine,

lumbar region, knees, and ankles, it is

believed that they may not have been

decorative. Examination of the Ice

Man's skeleton revealed that he had

been suffering from arthritis, and the

positioning of the tattoos at known

acupuncture points has persuaded

many researchers that Otzi's tattoos

served a therapeutic purpose.

The remains of the the Ice Man's

clothing were fairly well-preserved by

the ice. When he died, Otzi was wearing shoes made from a combination of

bearskin soles and a top of deer hide

and tree bark, with soft grass stuffed

inside for warmth. He also wore a woven grass cloak, which he probably also

used as a blanket, and a leather vest

and fur cap. Alongside the body, various articles, which the Ice Man had

been carrying with him on his last journey, were also discovered. These items

consisted of a copper axe with a yew

handle, an unfinished yew longbow, a

deerskin quiver with two flint-tipped

arrows and 12 unfinished shafts, a flint

knife and scabbord, a calfskin belt

pouch, a medicine bag containing medicinal fungus, a flint and pyrite for

creating sparks, a goat-fur rucksack,

and a tassel with a stone bead. All of

this was invaluable material for painting a picture of the life and death of

the Ice Man.

But who was this mysterious traveller, and what had prompted him to

venture 1.8 miles up into the desolate

Otzal Alps? DNA analysis has shown

that Otzi was most closely related to

Europeans living around the Alps.

Further isotopic analysis of his teeth

and bones by geochemist Wolfgang

Muller, of the Australian National University, together with colleagues in the

United States and Switzerland, have

narrowed Otzi's birthplace down to a

site near to the Italian Tyrol village of

Feldthurns, north of present-day

Bolzano, about 30 miles southeast of

the place where he met his death. High

levels of copper and arsenic found in

Otzi's hair show that he had taken part

in copper smelting, probably making

his own weapons and tools.

The first widely held theory as to

why the Ice Man was travelling alone

up in the Otztal Alps (and how he met

his death) was that he was a shepherd

who had been taking care of his flock

in an upland pasture. The hypothesis

was that he had been caught in an unseasonable storm and found shelter in

the shallow gully where he was found.

A variant on this theory, proposed by

Dr. Konrad Spindler, leader of the scientific investigation into the Ice Man,

was based on early x-rays of the body

taken at Innsbruck. These x-rays appear to show broken ribs on the body's

right side, which Spindler believed

were the result of some kind of fight which Otzi had become involved in

while returning to his home village

with his sheep. Although Otzi had escaped the battle with his life, he eventually died of the injuries in the place

where the hikers found him more than

5,000 years later. But new examinations of the body in 2001 by scientists

at a laboratory in Bolanzo showed that

the ribs had been bent out of shape

after death, due to snow and ice pressing against the ribcage. Another theory

connected the Ice Man with the various bog bodies, such as Tollund Man

and Lindow Man, recovered from the

peat bogs of northern Europe. Many

of the first millennium B.c. examples

of these bodies show that the victims

had eaten a last meal similar to that

of the Ice Man just before their death,

and appear to have been ritually sacrificed before being thrown into the

bog. Could the Ice Man have been a

ritual sacrifice? Dramatic findings

from the examinations at Bolanzo suggested otherwise.

A CAT scan of the body showed a

foreign object located near the shoulder, in the shape of an arrow. Further

examinations revealed that Otzi had

a flint arrowhead lodged in his shoulder. The Ice Man had been murdered.

A small tear discovered in Otzi's coat

appears to be where the arrow entered

the body. In June 2002, the same team

of scientists discovered a deep wound

on the Ice Man's hand, and further

bruises and cuts on his wrists and

chest, seemingly defensive wounds, all

inflicted only hours before his death.

Fascinatingly, DNA analysis shows

traces of blood from four separate

people on Otzi's clothes and weapons:

one sequence from his knife blade,

two different sequences from the same

arrowhead, and a fourth from his

goatskin coat. In light of these recent

discoveries, various new theories have

been put forward to explain what exactly happened to the Ice Man.

The presence of only the flint tip

of the arrowhead in the body indicates

that either Otzi or a companion must

have pulled the wooden shaft of the

arrow out. The CAT scan revealed that

the fatal arrow had been shot from

below and ripped upwards through

nerves and major blood vessels before

it lodged in the left shoulder blade,

paralyzing his left arm. The blood on

his coat may indicate that Otzi's companion was also wounded and had to

be carried on his shoulder. One scenario which has been suggested is that

Otzi and one or two companions were

a hunting group who took part in a

battle with a rival party, perhaps over

territory. The blood on Otzi's weapons

graphically illustrates that he must

have killed two of the enemy party,

removing his valuable arrowhead from

one body and then using it again, before receiving his own fatal wound.

Not everyone, however, agrees

with this version of events. According

to Walter Leitner of the Institute for

Ancient and Early History at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, Otzi

may have been a Shaman. Leitner believes that, because copper was a

scarce material in the Late Neolithic

period, only someone of great importance in the community would have

owned a copper axe. Shamans are also

known to commune with the spirit

world in remote locations, such as high

mountains. Otzi was probably murdered, Leitner thinks, but not in an argument over territory, but rather by

a rival group from the same community who wanted to assume power. By

killing the Shaman and claiming he

died in an accident, this end may have

been achieved. A further alternative

hypothesis is a sacrificial death where

the victim was ritually hunted down

and shot in the back with an arrow.

Such ritual killings are recorded by

Roman chroniclers as being practiced

by the Celts, and there is archaeological evidence from a skeleton discovered in the outer ditch at Stonehenge

that this kind of sacrifice took place

there (see Stonehenge article).

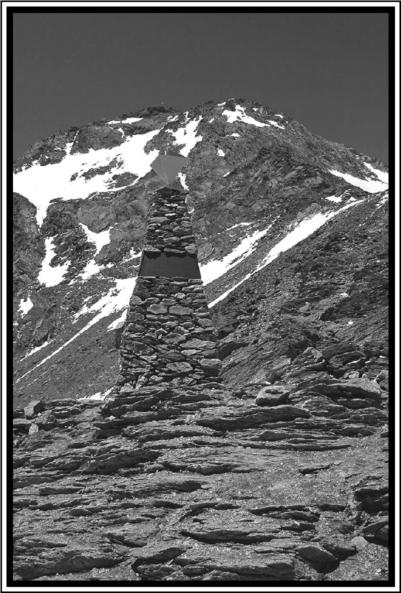

Photograph by Kogo. (GNU Free

Documentation License).

Otzi Memorial, Otztal.

Recently, a startling claim was

made by Lorenzo Dal Ri, director of

the archaeological office of the Bolzano

province. Dal Ri believes that the Ice

Man's death may actually have been

recorded on an ancient stone stela. The

decorated stone, of roughly the same

age as the Ice Man, had been used to

build the altar of a church in Laces, a

town close to the area where the discovery of Otzi was made. One of the

many carvings on the stela shows an

archer poised to fire an arrow into the

back of another unarmed man who appears to be running away. Although

there is no direct evidence to link the

stone with the murder of the Ice Man,

the resemblance between the carved

image and the death of Otzi is uncanny.

In February 2006, further light

was thrown on the Ice Man when

Dr. Franco Rollo (of the University of

Camerino in Italy) and colleagues examined mitochondrial DNA (DNA

only inherited through the mother)

taken from cells in the Ice Man's intestines. The team's conclusion was that

Otzi may have been infertile. Dr. Rollo

hypothesized that the social implications of his not being able to father offspring may have been a factor in the

circumstances which led to his death.

Since his discovery in 1991, Otzi

has achieved such popularity that he

even has his own version of the "Curse

of Tutankhamun." It has to be admitted that there appears to be a high

rate of mortality among the researchers connected with the discovery of

the Ice Man. Apparently the latest

victim was 63-year-old molecular

archaeologist Tom Loy, the discoverer

of the human blood on Otzi's clothes

and weapons, who died in mysterious circumstances in Australia in October

2005. Two other well-known names

connected with Otzi who have passed

away recently include Dr. Konrad

Spindler, head of the Ice Man investigation team at Innsbruck University,

who died in April 2005, apparently

from complications arising from multiple sclerosis; and the Iceman's original discoverer, 67-year-old Helmut

Simon, who plunged 300 feet to his

death in the Austrian Alps, in October 2004. Incidentally Dieter

Warnecke, one of the men who found

Simon's frozen body, died of a heart

attack shortly after Simon's funeral.

However, sceptics argue that the death

of five or six people associated with

the Ice Man over a 14 year period is

not a particularly unusual amount,

they also point out that mountaineers

naturally have a high rate of mortality

due to the dangers of their pursuit.

There are still many unanswered

questions about the life and death of

Otzi, now on display at the South Tyrol

Museum of Archaeology in BozenBolzano, Italy. Hopefully the answers

to some of these questions will become

apparent when scientists conduct the

autopsy to remove the flint arrowhead

from the Ice Man's shoulder. It looks

like we will have to wait until then for

more information on how and why Otzi

met his death in the frozen Alps, more

than 5,000 years ago.