Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (41 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

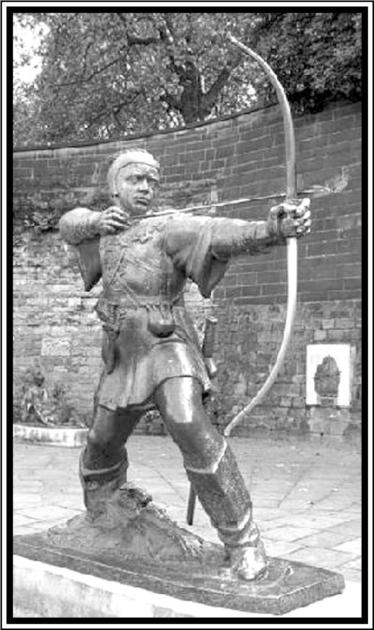

Photograph by M. Rees.

Statue of Robin Hood, Nottingham.

In the popular imagination, Robin

Hood is the archetypal English folk

hero. His legend, so familiar to people

all over the world, has remained relevant through hundreds of years of history, so that even Robin's band of

outlaws (Friar Tuck, Little John, Will

Scarlet, Allan a Dale, and Maid Marion)

have become household names. The

enduring appeal of the gallant

medievel outlaw, who steals from the

rich to give to the poor and fights

against the injustice and tyranny of authority figures such as Prince John and

the evil sheriff of Nottingham, shows

no signs of waning. But where does the story originate? Was there a real Robin

Hood hiding in the forests of medieval

England ready to defend the rights of

the poor and the oppressed?

Our earliest written refererence to

the outlaw, though it amounts to a

mere scrap, is in William Langland's

Piers Plowman written in 1377, where

one of the characters states "I know

the rhymes of Robin Hood." The next

notice, and the first where Robin is

classed as an outlaw, is in Andrew de

Wyntoun's Original Chronicle of Scotland, written around 1420. Under an

entry for the year 1283, the chronicle

describes Robin Hood and Little John

as well-known forest outlaws in

Barnsdale, Yorkshire, in the north of

England. Almost 20 years later, in the

Scotichronicon, Walter Bower mentions Robin Hood, "the famous cutthroat" and Little John, in an entry

under the year 1266. Bower puts the

outlaws in the context of Simon de

Montfort's rebellion against Henry III,

and again places them in Barnsdale

Forest, north of their traditional home

in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire.

However, at this time the forests of

England covered a much wider area

than they do today, and as Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire are adjacent

counties, it is possible that Robin

Hood's adventures spread over both

forests.

The remaining early references to

Robin Hood are from ballads and

songs, designed to be recited or sung

by wandering minstrels. The most significant early account in ballad form

is A Gest of Robin Hood, (gest probably meaning deeds), of which there

were a number of editions printed after 1500, following the development

of the printing press in England by

William Caxton. The story in the Gest,

again set in the forest of Barnsdale,

was once thought by some to date back

much earlier than the printed editions, perhaps as early as 1360 or 1400,

but nowadays a date of around 1450 is

more widely accepted. By the time of

these ballads, some of the elements of

the Robin Hood story as we know it

today were in place. Robin is accompanied not only by Little John, but Will

Scarlet, and Much the Miller's Son. His

enemies include the rich abbots of the

Catholic Church (whom he robs), and

the sheriff of Nottingham, and it is at

this time that we first see the appearance of the archery contest set up by

the sheriff to trap the outlaw. Robin

sees off his enemies, he beheads both

the sheriff of Nottingham and the

bounty hunter Guy of Gisborne. For the

murder of the sheriff, he is hunted down

in Sherwood Forest by King Edward

himself, but pledges his allegiance and

is pardoned. Robin subsequently finds

service at the court of the king, but becomes bored and restless with his position and returns to the forest where

he again lives as an outlaw. Many years

later he falls ill and journeys to visits

his cousin, the prioress of Kirklees Abbey, for medical treatment. But unbeknownst to him, she is the lover of

Robin's enemy Sir Roger of Doncaster,

and lets him bleed to death. Before he

dies, Robin shoots his last arrow out

of the window and tells Little John to

bury him where the arrow falls.

At this stage, however, there are

still some popular aspects of the tale

missing. The Normans are not yet portrayed as the villains, and there is no

fight against an evil Prince John, or

friendship with his benevolent

brother, King Richard the Lionheart. It was not until Sir Walter Scott's

Ivanhoe in 1819 that Robin Hood as the

Englishman fighting the Norman oppressor was established. Scott's novel

also made the character of Friar Tuck

a much more important part of the

story. In contrast to later plays and

stories where he is cast as a nobleman,

in the early ballads Robin is seen as a

yeoman (a tradesman or farmer), and

there is no mention of him giving to

the poor. It was not until 1598, in a

play intended for an aristocratic audience, that Robin's status was elevated

to become Robert, the Earl of

Huntingdon. It is also in the late 16th

century that the romance with Maid

Marion is first established, possibly in

plays written for the May Games,

spring celebrations which took place

in early May. But Maid Marion did not

become a main character until the publication of Thomas Love Peacock's

novel, Maid Marian, in 1822. She had,

however, been connected with the tale

since around 1500.

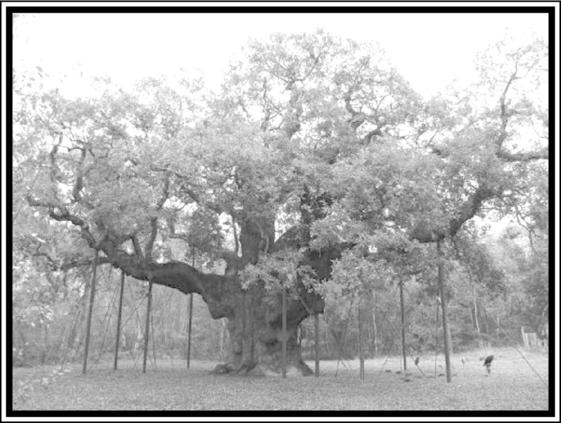

The Major Oak, an 800- to 1,000-year-old oak tree in Sherwood Forest,

Nottinghamshire, reputedly a hideout of Robin Hood.

Whether there is an historical figure behind these ballads, stories, and

plays, is another matter, though there

are certainly many candidates for the

historical Robin Hood. Unfortunately,

13th and 14th century English records

contain many references to people

with the surname Hood, and as Robert and its alternative form of Robin

was also a fairly common Christian

name at the time, finding the Robin

Hood of legend is extremely difficult.

There are, however, a few possibilities.

At the York assizes (county court) of

1226, a Yorkshireman named Robert

Hod is recorded as a fugitive, and in

1227 he appears again under the nickname Hobbehod, the meaning of which

is unclear. Unfortunately nothing more

is known of this Robert Hod. Another

possibility is Robert Hood, son of Adam

Hood, a forester who worked for John

De Warenne, the Earl of Surrey. He was

born in 1280 and lived in Wakefield,

Yorkshire, as a tenant, with his wife

Matilda. Wakefield is only 10 miles from Barnsdale, the setting of Robin's

escapades in the ballads, and in some

tales Robin Hood's father was said to

be a forester called Adam. The name

Matilda was also Maid Marian's real

name in two Elizabethan plays. In

1317, Robert Hode disappeared after

failing to report for military service.

Although there are certainly some

similarities between this Robin of

Wakefield and the Robin Hood of legend, the fact that stories surrounding

the Robin Hood name were already in

circulation during his lifetime would

suggest he is a little too late to qualify.

In fact, by this time court records show

that Robinhood had become an epithet

for an outlaw, and before 1300, there

were at least eight people who either

assumed the name or were given it.

This point is illustrated by the case

of William de Fevre, of Enborne in

Berkshire, who in 1261 is shown as an

outlaw in court records from Reading.

A year later at Easter, 1262, a royal

document renamed him William

Robehood. If this is not a clerical error,

then it is significant in that at the early

date of 1262, the Robin Hood legend

appears to have been well known

enough for other outlaws to be named

after him. If this is the case, it would

mean that any real Robin Hood cannot

be dated later than 1261 or 1262. Alternatively, it might also be evidence that

it was the Robin Hood nickname given

to outlaws at the time that inspired the

legend, so it cannot be taken as definite proof of such an early date for the

existence of Robin Hood.

A fascinating theory was put forward by Tony Molyneux-Smith in a

1998 book, entitled Robin Hood and the

Lords of Wellow, which suggests that

Robin Hood was not one single man,

but a pseudonym taken by descendants

of Sir Robert Foliot, who held the

Lordship of Wellow, close to Sherwood

Forest, up until the late 14th century.

This is intriguing, but further research

into this family and their origins is

clearly needed to positively identify

the Foliot family as the origin of the

famous outlaw tale.

Of course, Robin Hood was not the

first or the only medieval outlaw tale.

The daring escapes, rescues, and disguises of his legend have almost certainly been influenced by actual and

mythical exploits of real-life outlaws.

One example is the mercenary and pirate Eustace the Monk (c. 1170-1217).

His deeds are related in a 13th century romance and also by contemporary historian Matthew Paris, in the

Chronica Majora (Main Chronicle).

Another historical model for the Robin

Hood legend is Hereward (the Wake).

This 11th century outlaw leader led

the English resistance against William

the Conquerer and held the Isle of Ely,

in the swampy fenland of south

Lincolnshire, against the invading

Normans. Hereward became a folk

hero only a short time after his death,

and within 100 years his exploits were

being celebrated in song in taverns.

The legendary Hereward was already

established by the time of the Estorie

des Engles of Geoffrey Gaimar written

around 1140, and Gesta Herewardii

Saxonis (Deeds of Hereward the

Saxon) from the same period. Many

aspects of the outlaw hero later associated with Robin Hood are found

in the tales of Hereward. He was courageous, courteous, quick-witted, an

expert at disguise, and always alert, as can be understood from his name,

the Wake, meaning the watchful.

Another hero of the era was Fulk

FitzWarin. A tale belonging to the

start of the 12th century tells how

Fulk, as a young nobleman, is sent to

King John of England. Eventually, the

king becomes his enemy and confiscates his family's land, so Fulk takes

to the woods and lives as an outlaw.

Included in the story are incidents

particularly reminiscent of episodes in

the Robin Hood legend. For example,

Fulk tests the honesty of rich travelers he waylays, and tricks King John

into the forest to be captured by his

outlaw gang. There is, however, a

strong element of myth (giants, dragons, epic journeys) in the tale of Fulk

FitzWarin (and in all the early heroic

tales from England), which we do not

find in the Robin Hood legend.

A completely different interpretation of Robin Hood that has been put

forward is based on his role in English

folklore. Pagan themes such as the

Green Man (or Robin Goodfellow) and

the Wild Man of the Woods may have

influenced the growth of the Robin

Hood legend, and his character and

story was certainly incorporated into

the May Games, a celebration of nature

and the coming of spring, by the 16th

century. But the idea that Robin Hood

is only a legend that originated from

these celebrations is unlikely, especially as his story appears to have been

well-known prior to any association

with the May Games.

If Robin Hood existed at all, the

most convincing evidence places him

somewhere in the 13th century,

though it is more likely that he represents a typical outlaw hero, composed

in part from historical characters, but

not possessing an individual historical identity. The Robin Hood tale has

been built up gradually for more than

700 years, usually to meet the needs

and desires of his audience. In fact, it

is still developing today, as is evident

from the newest myths added to the

story, presented in the 1991 film Robin

Hood: Prince of Thieves, starring

Kevin Costner. Here, not only is Robin

placed at the end of the 12th Century

as a returning Crusader, but he is also

depicted fighting fierce painted Celtic

warriors in the forests, more than

1,000 years after they existed in reality. Without doubt, the tale will continue to develop and change in the

future as it has done in the past; this

is part of myth-history that is Robin

Hood.