Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (49 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

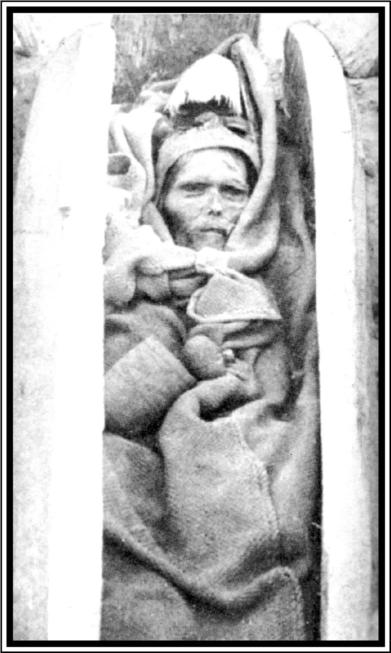

Tarim Basin mummy, photographed by Aurel Stein, c. 1910.

The Tarim Mummies constitute a

baffling ancient world mystery, and

one of the most remarkable archaeological finds of the 20th century. These

amazingly well-preserved human remains were found in the dry salty environment of the vast Taklimakan

desert, part of the Tarim Basin in western China. The bodies so far discovered

have an extremely wide date range,

from 1800 B.C. up until A.D. 400. But what

has captured the attention of scholars

all over the world is the fact that the

mummies have distinctly European features, and seem to represent various Caucasian tribes who lived in this

desolate area of western China up until 2,000 years ago, before mysteriously

disappearing.

The mummies were first discovered in the early 1900s by Swedish

explorer Sven Hedin, who was investigating the complex history of the Silk

Road, an ancient series of routes which

once led from China to Turkey and on

into Europe. But without the necessary equipment to either preserve the

bodies or transport them back to museums in Europe for study, they remained in situ and were soon forgotten.

In 1978, Chinese archaeologist Wang

Binghua excavated 113 of these bodies at a cemetery at Qizilchoqa, or Red

Hill, in the northeast corner of the central Asian province of Xinjiang. Most

of the bodies were later taken to a

museum in the city of Urumqi. In the

last 25 years or so, Chinese and

Uyghur archaeologists have carried

out sophisticated excavation and research in the area, and there are now

more than 300 of these mummies

known to have been discovered in western China. In 1987, Victor Mair (a professor of Chinese and Indo-Iranian

literature and religion at the University of Pennsylvania) was leading a

group of tourists through the museum

in Urumqi when he came upon some

of the mummies excavated by Wang

Binghua. He found it an unnerving

experience. All were dressed in dark

purple woolen garments and felt boots,

and their bodies were almost perfectly

preserved. Fascinatingly, all the mummies had European features: brown or

blonde hair; long noses and skulls;

slim elongated bodies; and large,

deepset eyes.

Due to the political climate in

China at the time, Mair was not able

to do anything about the amazing

finds, but in 1993 he returned with a

team of Italian geneticists who had

worked on the Ice Man. The group

went back to Wang Binghua's Red Hill

site to examine corpses that had been

reburied due to lack of storage space

at Urumqi Museum. Mair and his team

took DNA samples from the bodies,

which proved that the mummies were

Caucasoid. Mair's research also seems

to show that the earliest of these European mummies represented the first

settlers in the Tarim Basin.

The oldest of all the western Chinese mummies is known as the Beauty

of Loulan. The perfectly preserved

Loulan female body was discovered by

Chinese archaeologists in 1980, near

the ancient town of Loulan, situated

on the northeastern edge of the

Taklimakan desert. This woman, who

died at the age of 40 around 4,800 years

ago, was only 5-feet 2-inches tall, and

had European features including a

steep nose bridge, high cheekbones,

and blondish-brown hair, which had

been rolled up under a felt headdress.

She was wearing a woolen shroud and

leather boots, and buried with her in

the grave was a comb and a beautiful

straw basket that contained grains of

wheat. Another expedition to the

Loulan region in 2003, by the Xinjiang

Archaeological Institute, revealed

some remarkable finds. Excavations

were undertaken at a cemetery consisting of a sand mound measuring 25

feet in height, located 110 miles from

the ancient town of Loulan. A particularly interesting find at the grave

site was made close to the center of the mound, and proved to be another

impressive mummy. Contained in a

boat-shaped coffin, the female mummy

had been wrapped in a woolen blanket and was wearing a felt hat and

leather shoes. She had been buried

with a red-painted face mask, a bracelet containing a jade stone, a leather

pouch, a woolen loincloth, and ephedra sticks. Ephedra is a medicinal

shrub that was used in the Zoroastrian

religious rituals of Iran, so there was

perhaps some connection between

these two areas.

A further group of mummies found

in the Tarim Basin region consisted of

one man, three women, and a baby, and

have become known as the Cherchen

Mummies. The four adult bodies,

thought to date to around 1000 B.C.,

were dressed in the same color, with

red and blue cords wrapped around

their hands, perhaps indicating a close

kinship. Chercean Man, the male

mummy, was more than 6-feet tall and

died at the age of 50. He had long, light

brown, braided hair; a thin beard; and

multiple tattoos on his face. The man

was buried with no less than 10 different styled hats and was dressed in a

purple and red two-piece suit. Similar to Cherchen Man, the main female

burial had numerous tattoos on her

face, and was almost 6-feet tall. She

was wearing a red dress and white

deer skin boots, and had her light

brown hair gathered in two long plaits.

There was also a three-month-old baby

buried with the adults, who was wearing a blue felt bonnet, and had blue

stones covering its eyes. Buried beside

the infant were a cow-horn cup and a

nursing bottle made from a sheep's

udder. The family is thought to have

died in some sort of epidemic.

What has fascinated archaeologists

most about these discoveries is the

amazing preservation of the brightlycolored and patterned European-looking clothing the people were wearing.

Dr. Elizabeth Barber, professor of linguistics and archaeology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, has made a

detailed study of the textiles recovered

from the Tarim Basin and found striking similarities to Celtic tartans from

northwest Europe. She has also proposed that the tartan from the Tarim

mummies and that from Europe share

a common origin in the Caucasus

mountains of southern Russia, where

the earliest evidence for such fabrics

dates back at least 5,000 years. The

rich array of textile finds from western Chinese mummy burials includes

robes, caps, shirts, cloaks, tartanweave trousers, and striped woolen

stockings. At Subeshi on the northern

route of the Silk Road, three female

mummies, dating from around 500 to

400 B.C., were found with enormously

tall, pointed hats, and have since become known as the Witches of Subeshi.

But who were these apparently

European peoples and what were they

doing in western China? The mummies are scatterred over such a wide

geographical area and date range

that there can be no question that

they are a single tribe. They seem to

represent several eastward migrations from different areas over a thousand or more years. There are some

ancient sources referring to groups

inhabiting the areas of the Tarim basin, where mummies have been found,

which may give a clue to the origins

of at least some of the mummy people.

First millennium B.C. Chinese sources

mention a group of "white people with long hair" known as the Bai people.

The Bai lived on the northwestern

border of China, and the Chinese apparently bought jade from them. Another group on the northwestern

borders of China were the Yuezhi,

mentioned in 645 B.C. by the Chinese

author Guan Zhong. The Yuezhi also

supplied the Chinese with jade, which

they got from the nearby mountains of

Yuzhi at Gansu. After being defeated

by the nomadic Xiongnu people, the

majority of the Yuezhi migrated to

Transoxiana (part of southern Asia

equivalent to modern Uzbekistan and

southwest Kazakhstan) and later to

northern India, where they founded

the Kushan Empire. Depictions of

Yuezhi kings on coinage have suggested to some that this group may

have been a Caucasoid people.

The final group who inhabited this

area were the Tocharians, who represent the easternmost speakers of an

Indo-European language (a language

group comprising most of the languages of Europe, India, and Iran).

Some scholars argue that the

Tocharians and the Yuezhi were in fact

the same people under different

names, though there is no proof of this

at present. The areas of western

China where European-type mummies have been found, in the northeastern part of the Tarim basin, and

further east in the area around

Lopnur, correspond well to the later

distribution of the Tocharian language. Chinese writings mention that

the Tocharians had blond or red hair,

and blue eyes. Frescoes from Buddhist

caves in the Tarim Basin dating to the

ninth century A.D. show a people with

distinctly European features. The

Tocharians remained in the Tarim basin and later adopted Buddhism from

northern India, their culture surviving at least until the eighth century

A.D., when they seem to have been assimilated by the Uighur Turks of the

eastern Asian steppes.

Although no Tocharian texts have

ever been found together with mummies in the Tarim basin, the almost

identical geographical location of both,

as well as depictions of Tocharians

showing European features, strongly

suggests that at least some of the

mummy people of the area were the

ancestors of the Tocharians. But did

these people trek all the way across

Europe and half of Asia to find their

homeland in the and deserts of western China? Judging by the textile evidence for the origin of tartan in the

Caucasus mountains of south Russia,

and the linguistic evidence placing the

beginnings of the Indo-European language in the same area, it seems that

perhaps there was migration from the

Caucasus at a very early date. Dr.

Elizabeth Barber hypothesizes that

there may have been two migrations

from the possible Indo-European

homeland northwest of the Black

Sea-one to the west, resulting in

Celtic and other European civilizations; and the other migration, the

ancestors of the Tocharians, moving

east, and eventually finding their way

into the Tarim basin of central Asia.

In light of the finds of the Tarim mummies, the theory that east and west

developed their civilizations in complete isolation from each other may

have to be abandoned.

© Scott Brown

Thetford Forest, Norfolk, where the Green Children are

said to have roamed.