High Heat (2 page)

Authors: Tim Wendel

I nodded, contemplating what the old slugger had said.

“But then, in the next breath, other guys come to mind,” Howard added. “There's Satchel Paige and Walter Johnson, the âBig Train' himself. And sure as you and I are sitting here tonight, there's a bunch of modern-day guys you have to mention.”

“Billy Wagner, Tim Lincecum, Joba Chamberlain, Jonathan Papelbon,” I offered.

“And that kid down at Tampa Bay. The one who did so well in the playoffs.”

“David Price?”

“That's right, Price. He looks plenty fast to me.”

As Howard and I talked, I realized that baseball was different from other sports and acts of athletic prowess. In the national pastime, there is no direct correlation between physical size and the velocity of a quality fastball. For example, onetime Baltimore Orioles phenom Steve Dalkowski stood 5-foot-11, weighed maybe 170 pounds. In comparison, Feller was 6-foot, 185 pounds. Johnson, the “Big Train,” was slightly taller and heavier, but Koufax was actually even taller in stature and Paige bigger than most. Yet, in the end, such dimensions hardly mattered. It was as if the Great Maker in the sky stood all the hopefuls who ever wanted to pitch in the major leagues shoulder to shoulder and only a rare few were bestowed with the ultimate blessing of pure, undeniable speed. Fewer still were able to wrestle this angel toward earth, to harness and truly embrace the gift from above. For many more the ability to throw hard, despite all their best efforts, remained nothing more than an untamed curse.

For those who can master the lessons of throwing high heat, history awaits. Not only do they become part of baseball lore, but their stories often extend into our national story, echoing through our collective consciousness. They become the icons kids throwing out on the Little League field want to be. Perhaps that's the ultimate allure and mystique of the fastball: The ones who can really bring it will always somehow speak to us.

“No, the question you're asking doesn't have a pat answer,” Howard said. “To my mind, it's one of those riddles where the chase becomes what's important, if you catch my drift. You're going to have to hit the road some to really tease this out.”

With that the slugger drained what was left in his glass and got to his feet. “It may not be easy to figure out,” he said, “but it sure would be a talker, wouldn't it? Now if you'll excuse me.”

“Good night,” I said. “And thanks.”

Across the room, a set of glass doors opened up onto the ballpark. For games, this was the portal for the affluent and well connected to stroll between their seats behind home plate and the bar and buffet here in the Presidents Club. Realizing that I might never have this opportunity again, I decided to check out the plushest seats in town.

Outside, the evening air held a hint of winter, and out beyond the outfield fence, the echoes of the nation's capital rose into the darkening sky. Howard was right: To determine the fastest pitcher ever, I was going to need to talk with the game's greats, try to chase down as many ghosts as I could find. The journey wouldn't be a straight line to the plate, but it promised to be a lot of fun.

The Windup

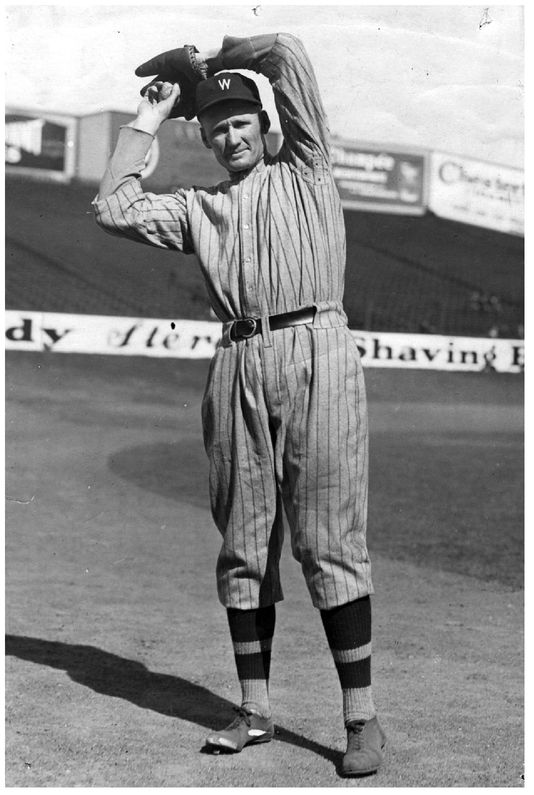

Walter Johnson

Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

You can't hit what you can't see.

âFRANK “PING” BODIE

Â

Â

Slowness has never been an American characteristic.âFRANKLIN ROOSEVELT

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

B

ob Feller agreed to the stunt because he was as curious as everybody else. How fast could he really throw a baseball? Where did he possibly rank among baseball's fastest of the fast?

ob Feller agreed to the stunt because he was as curious as everybody else. How fast could he really throw a baseball? Where did he possibly rank among baseball's fastest of the fast?

That's what led him to the middle of a closed-off street running through Chicago's Lincoln Park that sunny morning in the summer of 1940. Standing there with a baseball in his right hand, waiting and then momentarily flinching as the Harley Davidson motorcycle with a city policeman roared closer to him.

Feller did as he had been instructed. As the Harley bore down at him, now going better than 80 miles per hour, Feller went into his windup. It wasn't a carbon copy of the distinctive high-leg-kick delivery that he exhibited on the mound. What he would normally perform in a big-league ballpark with a batter standing at the plate. How could it be? After all, Feller was in street clothes instead of a ballplayer's uniform. In wingtips instead of spikes and toe plate. Fresh from the Del Prado Hotel at 53rd and Hyde Park Avenue. Still, the Cleveland Indians' phenom was able to put plenty of zip on the ball. Just as importantly, the 21-year-old also threw the baseball accurately

toward one of the two bull's-eye targets Major League Baseball's Office of the Commissioner had erected for the bizarre test.

toward one of the two bull's-eye targets Major League Baseball's Office of the Commissioner had erected for the bizarre test.

“I was there because we all want to know, deep down,” Feller says, “who was the fastest of all time.”

That's what led me to fly nearly 70 years later to Cleveland, where the longtime Indians pitcher still makes his home. On the phone, a few days before, I'd offered to meet Feller wherever he wanted. But coffee and chitchat over the family kitchen table or at the Starbucks around the corner isn't exactly Rapid Robert's style. “At the ballparkânine sharp,” he said in a loud, brassy voice. As soon as I replied, “OK,” he hung up. Feller sure left the impression that he doesn't tolerate any tardiness.

I enjoy going to Cleveland because it reminds me an awful lot of home. I grew up outside of Buffalo, New York, a three hours' drive away. Both cities hug Lake Erie and were once capitals of commerce, with the accent on shipping and heavy industry. Of course, such enterprises hit the skids long ago and the goal became how a city could reinvent itself. Playing off its link with the beginnings of rock and roll (local disc jockey Alan Freed coined the term “rock and roll”), Cleveland edged out Memphis as the permanent home to a museum and hall of fame. Cleveland's civic leaders pledged $65 million in public money to fund the construction. That financial package put the project over the top. As

Cleveland Plain Dealer

music critic Michael Norman later said, “It wasn't Alan Freed. It was $65 million. Cleveland wanted it here and put up the money.”A pyramid-style shrine was erected to honor the Beatles, Chuck Berry, Bruce Springsteen, and other rockers along the harbor front, not far from where old Municipal Stadium once stood, the ballpark where Feller was a star. The Indians' new digs are also located downtown and, along with the Rock and Roll Museum, have fostered a renaissance in these parts.

Cleveland Plain Dealer

music critic Michael Norman later said, “It wasn't Alan Freed. It was $65 million. Cleveland wanted it here and put up the money.”A pyramid-style shrine was erected to honor the Beatles, Chuck Berry, Bruce Springsteen, and other rockers along the harbor front, not far from where old Municipal Stadium once stood, the ballpark where Feller was a star. The Indians' new digs are also located downtown and, along with the Rock and Roll Museum, have fostered a renaissance in these parts.

In a way, the Rock and Roll Museum can be seen as a nod to our continued infatuation with speed. The average pop song is three to four minutes long. The MTV videos, which run in looped presentations at the museum in Cleveland, are minimovies created around a song. Of

course, Feller has no interest in checking out the computerized “jukebox,” containing virtually every song of every performer inductee, at the Rock and Roll museum. He's more of an easy-listening fan and always liked the Big Band sound. Still, Feller says he's happy that such civic landmarks bring visitors. “You need the out-of-towners,” he says. “Without them, everything can get desperate in a hurry.”

course, Feller has no interest in checking out the computerized “jukebox,” containing virtually every song of every performer inductee, at the Rock and Roll museum. He's more of an easy-listening fan and always liked the Big Band sound. Still, Feller says he's happy that such civic landmarks bring visitors. “You need the out-of-towners,” he says. “Without them, everything can get desperate in a hurry.”

At 8:50 a.m., I'm ushered by a member of the Indians' public relations staff into a conference room at Jacobs Field. The room overlooks the emerald-green field several stories below. Feller is already there, waiting for me. He has a videotape of the motorcycle test and as we watch it for the first of several times, a small crowd of ballclub employees gathers to view the show.

“I guess it's our fascination with speed,” Feller says, again cuing up the two-minute clip. “Who was the fastest pitcher of all time? The world will never know, may never agree, but it sure is fun to talk about, isn't it?”

That sunny day in Chicago was a generation before radar guns and such modern-day timing devices. So, Lew Fonseca, a player for 12 years in the major leagues, the American League batting champion in 1929, devised what will forever be remembered as the motorcycle test to clock Feller's legendary fastball. At the time Fonseca produced instructional baseball films. If he could capture Feller's speed on film, he believed he could precisely track and calibrate how fast the baseball was traveling. But to do so, Feller seemingly had to do the impossible: hit his bull's-eye target, about the size of a cantaloupe, from 60 feet, 6 inches away, just after the motorcycle roared past him.

The Harley motorcycle had a 10-foot head start on Feller's fastball and was doing 86 miles per hour when it flew by, just a few feet to the right of the Indians' ace. At that moment in U.S. history, Feller was just about the most famous ballplayer, certainly the most famous pitcher, in the land. Soon after he began pitching for Cleveland, at the age of 18, he was on the cover of

Time

magazine. Three seasons later, on this summer day in Chicago, Feller was arguably the best pitcher, the fastest fireballer, in the game. He was on the verge of leading the

American League in victories for the second time in three consecutive seasons and being the strikeout leader for the third time in four seasons. But in Europe and on the far rim of the Pacific, World War II was building, and too soon Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, and the other stars of this era would leave the national pastime to enlist. Perhaps that's what makes the motorcycle test even more incongruous and precious when seen in the rearview mirror of today. Here's a window to a world before the Best Generation was tested by Pearl Harbor and Hitler. Feller's boyish face could be from any era. He smiles sheepishly as the cameras begin to roll. He knows he has the world on a string and has arrived at that station in life when participating in such a jerry-rigged experiment, the morning of a game in Chicago, somehow made complete sense.

Time

magazine. Three seasons later, on this summer day in Chicago, Feller was arguably the best pitcher, the fastest fireballer, in the game. He was on the verge of leading the

American League in victories for the second time in three consecutive seasons and being the strikeout leader for the third time in four seasons. But in Europe and on the far rim of the Pacific, World War II was building, and too soon Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, and the other stars of this era would leave the national pastime to enlist. Perhaps that's what makes the motorcycle test even more incongruous and precious when seen in the rearview mirror of today. Here's a window to a world before the Best Generation was tested by Pearl Harbor and Hitler. Feller's boyish face could be from any era. He smiles sheepishly as the cameras begin to roll. He knows he has the world on a string and has arrived at that station in life when participating in such a jerry-rigged experiment, the morning of a game in Chicago, somehow made complete sense.

“It was kind of a cute idea,” Feller says. “I suppose I wanted to know as badly as everybody else how hard I could throw a baseball. Since I'd been a little guy, I'd heard people talking about how I was the next Lefty Grove or Walter Johnson.

“You look back at it now and ask yourself, âWhat the heck were you doing?' But I knew I could throw the ball with the best of them. Deep down if somebody asks you to try and prove it, you step right up and give it a shot. No questions askedâyou know what I mean?”

Seconds after the motorcycle flew past, Feller flung the regulationsize hardball. The ball quickly outraced man and machine, ahead by a good three feet when it split the paper bull's-eye target that was held upright by a wooden frame. Alongside Feller's target was another 10-foot-high target that the motorcycle sped toward. More importantly for the matters of science, Feller's speed ball hit the 12-inch-diameter dark bull's-eye in the center of the heavy paper.

“To this day I still don't know how I hit that target on the first try,” Feller tells the growing audience at Jacobs Field. “It was the luckiest thing I've ever done.”

“As lucky as pitching a no-hitter on Opening Day?” somebody sings out.

“Hey, don't be getting silly on me,” Feller snaps back. “But afterward I told those guys doing this test, âGive me another fifty chances

and there's no way I can duplicate that.' I don't know if they believed me or thought I was just blowing smoke.”

and there's no way I can duplicate that.' I don't know if they believed me or thought I was just blowing smoke.”

Seconds after Feller's offering broke the paper target, the motorcycle obliterated its target and Fonseca had satisfied enough variables to calculate the speed of the pitch. Soon afterward, MLB announced that Feller's fastball had been clocked going 104.5 miles per hour. Feller's throw gained 13 feet on the motorcycle over the 60 feet, 6 inches. So, with the motorcycle traveling at 86 milers per hour the calculation goes as follows: 86 divided by 60.5 equals 1.42. Now, add in the 13 feet plus 60.5. That equals 73.5. Multiply it by the previously calculated 1.42 and you have nearly 104.5 miles per hour.

That sounds pretty definitive and it certainly ranks Feller among the fastest pitchers ever in the game. But does that really make him the fastest of all time? Even Feller, a guy who isn't afraid to speak his mind or polish his accolades, isn't so sure. “I know it puts me in the ballpark,” he says. “I know there's no arguing with that. But I'm also not foolish enough to think that's the end of the story.”

Indeed, we're just getting started.

Â

Â

T

wo weeks before Christmas in 2008, I'm driving from Washington, D.C., just ahead of the worst ice storm to hit the Northeast in years. Climbing into the mountains north of Harrisburg, through the freeway roller-coaster ride leading into Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, the weather changes from freezing rain to sleet mixed with snow. The early-morning forecast back home in Washington called for a few inches of snow, which I'm somewhat prepared for. A shovel lies in the rear cargo compartment. But a wintry mix, of course, can be an entirely different story.

wo weeks before Christmas in 2008, I'm driving from Washington, D.C., just ahead of the worst ice storm to hit the Northeast in years. Climbing into the mountains north of Harrisburg, through the freeway roller-coaster ride leading into Wilkes-Barre and Scranton, the weather changes from freezing rain to sleet mixed with snow. The early-morning forecast back home in Washington called for a few inches of snow, which I'm somewhat prepared for. A shovel lies in the rear cargo compartment. But a wintry mix, of course, can be an entirely different story.

Other books

Worth Dying For by Denise, Trin

Ruthless by Steven F. Freeman

The Merry Misogynist by Colin Cotterill

Supernatural 10 - Rite of Passage by John Passarella

The Man Who Couldn't Lose by Roger Silverwood

Going for the Blue by Roger A. Caras

Souvenirs of Murder by Margaret Duffy

Elfhame (Skeleton Key) by Anthea Sharp, Skeleton Key

Borrowed Vows by Sandra Heath

All That Matters by Paulette Jones