Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (34 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

11.51Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

He began work on the first of his Pellucidar novels in 1912 while the manuscript of

Tarzan of the Apes

was still making the rounds of book publishers, collecting rejection slip after rejection slip as it went. His working title was “The Inner World.”

All-Story

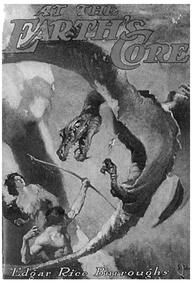

ran it serially in four issues starting on April 4, 1914. It didn’t appear as a book until 1922, when A. C. McClurg, Burroughs’s publisher for many years, brought it out with a wonderful cover, both menacing and sexy, by J. Allen St. John, the best illustrator of Burroughs’s early work.

Tarzan of the Apes

was still making the rounds of book publishers, collecting rejection slip after rejection slip as it went. His working title was “The Inner World.”

All-Story

ran it serially in four issues starting on April 4, 1914. It didn’t appear as a book until 1922, when A. C. McClurg, Burroughs’s publisher for many years, brought it out with a wonderful cover, both menacing and sexy, by J. Allen St. John, the best illustrator of Burroughs’s early work.

The first edition of

At the Earth’s Core

(1922) was illustrated by J. Allen St. John; the cover shows David Innes rescuing Dian the Beautiful. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

At the Earth’s Core

(1922) was illustrated by J. Allen St. John; the cover shows David Innes rescuing Dian the Beautiful. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

His hollow earth story’s most obvious debt was to Jules Verne’s novel

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

(1864). Another likely influence was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s

The Lost World,

which was a best seller in 1912. In Doyle’s novel, the lost world, discovered by British explorers, lay not in the hollow earth but on a vast plateau surrounded by cliffs rising above the South American jungle, isolated for eons, unchanged since the Jurassic Period. This remote, unapproachable tableland was crawling with prehistoric life—huge, scary dinosaurs in particular. The clashing prehistoric reptiles in Verne’s

Journey

played only a minor part in the novel overall. As we’ve seen, dinosaurs had captured the popular imagination ever since their “invention” in the early nineteenth century and the coining of the term by Sir Richard Owen in 1841. Life-size reconstructions featured at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London (and the splashy formal dinner thrown by sculptor/promoter Waterhouse Hawkins inside a half-constructed Iguanodon) cemented popular interest, which Verne drew on for his prehistoric novel.

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

(1864). Another likely influence was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s

The Lost World,

which was a best seller in 1912. In Doyle’s novel, the lost world, discovered by British explorers, lay not in the hollow earth but on a vast plateau surrounded by cliffs rising above the South American jungle, isolated for eons, unchanged since the Jurassic Period. This remote, unapproachable tableland was crawling with prehistoric life—huge, scary dinosaurs in particular. The clashing prehistoric reptiles in Verne’s

Journey

played only a minor part in the novel overall. As we’ve seen, dinosaurs had captured the popular imagination ever since their “invention” in the early nineteenth century and the coining of the term by Sir Richard Owen in 1841. Life-size reconstructions featured at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London (and the splashy formal dinner thrown by sculptor/promoter Waterhouse Hawkins inside a half-constructed Iguanodon) cemented popular interest, which Verne drew on for his prehistoric novel.

In 1884 the discovery of a fossil herd of articulated Iguanodon skeletons in a Belgian coal mine further heightened dinosaurmania, as did the 1886 publication of

Le monde avant la creation del ’homme

, by Camille Flammarion (1842–1925), which pictured an Iguanodon rampaging in the streets of Paris—the precursor to all those Godzilla movies. In the late 1890s, the New York Museum of Natural History bought famed dinosaur hunter Edward Drinker Cope’s collection and commenced creating dramatic displays that were enthusiastically attended. Dinosaurs hadn’t been used much in literature except by Verne, and then only in a minor role. In

The Lost World

they take center stage for the first time. Although Verne was the first to use them in fiction, the real origins of our ongoing pop cult love affair with dinosaurs—which reached an apotheosis of sorts in the

Jurassic Park

movies

—

can be traced to Doyle’s novel, which remains so popular that an adventure series based on it ran for several years on television starting in 1999. While

The Lost World

was still on top of the best-seller lists, Burroughs was casting around for a new writing project. He seems to have combined Verne’s hollow earth premise with Doyle’s teeming prehistoric world, adding quite a few brainstorms of his own.

Le monde avant la creation del ’homme

, by Camille Flammarion (1842–1925), which pictured an Iguanodon rampaging in the streets of Paris—the precursor to all those Godzilla movies. In the late 1890s, the New York Museum of Natural History bought famed dinosaur hunter Edward Drinker Cope’s collection and commenced creating dramatic displays that were enthusiastically attended. Dinosaurs hadn’t been used much in literature except by Verne, and then only in a minor role. In

The Lost World

they take center stage for the first time. Although Verne was the first to use them in fiction, the real origins of our ongoing pop cult love affair with dinosaurs—which reached an apotheosis of sorts in the

Jurassic Park

movies

—

can be traced to Doyle’s novel, which remains so popular that an adventure series based on it ran for several years on television starting in 1999. While

The Lost World

was still on top of the best-seller lists, Burroughs was casting around for a new writing project. He seems to have combined Verne’s hollow earth premise with Doyle’s teeming prehistoric world, adding quite a few brainstorms of his own.

The landscape, ecology, and cosmology of Pellucidar are delightfully wacky and definitely all-American, starting with the way mining magnate David Innes and inventor Abner Perry got there: in an experimental mining machine run amok. Perry has invented an “iron mole,” a “mechanical subterranean prospector” consisting of “a steel cylinder a hundred feet long, and jointed so that it may turn and twist through solid rock if need be. At one end is a mighty revolving drill.” It’s a sort of segmented steam locomotive with a huge Roto-Rooter attached to the front. Burroughs may well have been inspired to create this curious device based on his gold mining days, and also by reading the

Chicago Tribune

comics page. Dale R. Broadhurst says in an article in

ERBzine,

Chicago Tribune

comics page. Dale R. Broadhurst says in an article in

ERBzine,

A likely source for the “Iron Mole” may be found in 1910 issues of the Sunday

Chicago Tribune

, where cartoonist M. L. Wells chronicled in color his “Old Opie Dilldock’s Stories.” In one of these 1910 illustrated Sunday full-pages, Opie plans a trip to the south pole and constructs an “earth borer” in his secret workshop, in order to make the trip there by way of a straight line through the Earth. Utilizing a hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell for power, the ingenious inventor propels his contraption to “the center of the earth.” There he discovers strange intelligent beings … one of which he takes with him on his return to the planet’s surface. While I doubt very much that Edgar Rice Burroughs sat down with a pile of “Opie Dilldock’s Stories,” in order to write out his 1913 “Inner World” adventure, some story elements from this set of locally published cartoons may well have entered into the would-be author’s inner fantasies, and from there flowed out onto his pages of fiction, probably more by happenstance than through his conscious design.

63

Innes and Perry have built this machine not to advance knowledge and exploration, but to extend the frontiers of coal mining beyond those of mortal men—and make tons of money while they’re at it. But on its trial run, the steering freezes and the damn thing won’t stop—commencing to bore its way like crazy straight for the center of the earth.

After tearing through five hundred miles of rock, the iron mole pops out in sunny, tropical Pellucidar. “Together we stepped out to stand in silent contemplation of a landscape at once weird and beautiful.” But in nothing flat, “there came the most thunderous, awe-inspiring roar that ever had fallen upon my ears.” It’s a colossal bearlike creature the size of an elephant—a dyryth—and it’s after them. But it’s distracted by the sudden appearance of a wolf pack a hundred strong, quickly followed by their masters, black “manlike creatures” with dracula teeth and long, slender tails, “grotesque parodies on humanity.” These are but one of several races of varying intelligence inhabiting Pellucidar. They capture Innes and Perry and race through the treetops to their arboreal bough-village high in the trees.

Pellucidar is a busy, complicated place. As the

ERBzine

puts it, “The land teems with plant and animal life. A veritable melting pot where animals of nearly all the geological periods of the outer crust exist simultaneously. The land’s races are just as varied as its animal life.” Burroughs seems to have adopted the kitchen sink theory of the hollow earth, throwing in everything he can think of. More is more.

ERBzine

puts it, “The land teems with plant and animal life. A veritable melting pot where animals of nearly all the geological periods of the outer crust exist simultaneously. The land’s races are just as varied as its animal life.” Burroughs seems to have adopted the kitchen sink theory of the hollow earth, throwing in everything he can think of. More is more.

Innes and Perry escape from the tree creatures only to be captured by another vaguely hominid species called the Sagoths. They look like gorillas and are slave masters to yet another species—Stone Age humans. Innes and Perry are added to the chain gang and get to know a few of the enslaved humans—Ghak the Hairy One, Hooja the Sly One, and Dian the Beautiful. They’re on a forced march to the village of the evil Mahars.

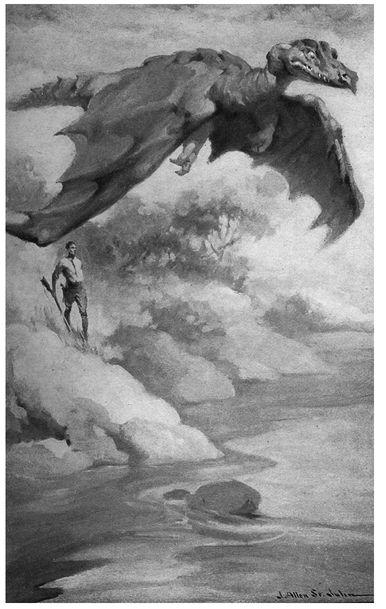

The dominant species on Pellucidar, the Mahars are a master race of super-intelligent lizards. They “are great reptiles, some six or eight feet in length, with long narrow heads and great round eyes. Their beaklike mouths are lined with sharp, white fangs, and the backs of their huge lizard bodies are serrated into bony ridges from their necks to the end of their long tails, while from the fore feet membranous wings, which are attached to their bodies just in front of the hind legs, protrude at an angle of 45 degrees toward the rear, ending in sharp points several feet above their bodies.”

Voiceless and unable to hear, the Mahars “communicate by means of a sixth sense which is cognizant of a fourth dimension.” Whatever that may mean. Their capital is an underground city called Phutra, where they’re served by the gorilla-like Sagoths and keep crowds of humans as cattle, since the Mahars consider human flesh quite a delicacy. They enjoy watching Roman-style combat in their great amphitheater between vicious beasts and lowly humans, on whom they also perform “scientific” experiments à la Joseph Mengele. A really nasty bunch, the Mahars, sort of like brainy flying Komodo dragons with Nazi proclivities.

A Mahar in flight, in a drawing by St. John from the first edition of

At the Earth’s Core.

(© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

At the Earth’s Core.

(© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

But oddest about them—and telling in regard to Burroughs, whether he intended it or not—is that the Mahars are an

all-female

society. These reptilian incarnations of evil are all girls! Like the Mizorans, many generations ago the Mahars learned how to procreate without the unnecessary complication of having males around—“a method whereby eggs might be fertilized by chemical means after they were laid.” The implication, however unintentional, is that the twisted evil Mahars are what you get if women are left to their own devices. There’s a definite undercurrent of misogyny here, despite all the praises heaped on noble, pure-as-the-driven-snow Dian the Beautiful (whose characterizing epithet is also revealing in regard to Burroughs’ ideas about women—she’s not Dian the Smart, or Dian the Resourceful, or Dian the Independent).

all-female

society. These reptilian incarnations of evil are all girls! Like the Mizorans, many generations ago the Mahars learned how to procreate without the unnecessary complication of having males around—“a method whereby eggs might be fertilized by chemical means after they were laid.” The implication, however unintentional, is that the twisted evil Mahars are what you get if women are left to their own devices. There’s a definite undercurrent of misogyny here, despite all the praises heaped on noble, pure-as-the-driven-snow Dian the Beautiful (whose characterizing epithet is also revealing in regard to Burroughs’ ideas about women—she’s not Dian the Smart, or Dian the Resourceful, or Dian the Independent).

The secret of the Mahars’ parthenogenesis is kept in a single book stored in a vault deep beneath Phutra. There’s only one copy, and none of the high-I.Q. Mahars seems to have memorized the formula, which gives Perry an idea. As they wait around in their cell, Perry prays continually and has a flash: “David, if we can escape, and at the same time take with us this great secret, what will we not have accomplished for the human race within Pellucidar!”

“Why, Perry! You and I may reclaim a whole world! Together we can lead the races of men out of the darkness of ignorance into the light of advancement and civilization. At one step we may carry them from the Age of Stone to the twentieth century.”

“David, I believe that God sent us here for just that purpose!”

“You are right, Perry. And while you are teaching them to pray I’ll be teaching them to fight, and between us we’ll make a race of men that will be an honor to us both.”

Note the grandiosity—they’ll be doing this to honor themselves. Probably just hasty, imprecise writing (at another point Burroughs has a character say he won’t “stand supinely” watching), but also revealing of what’s to come.

By this time Perry has figured out Pellucidar’s cosmology. Its provenance encompasses hollow earth thinking going all the way back to Edmond Halley. Centrifugal force has caused the hollowness. As the spinning earth cooled, matter was thrown out to the edges, except for a “small superheated core of gaseous matter” that remained in the center as Pellucidar’s never-setting sun. This is a slap in the face of Newtonian physics, of course, since a sun existing in the center of the earth would either burn the whole globe to a cinder, and/or its gravity would cause the hollow sphere to collapse. But it’s both futile and somehow unfair to insist on plausibility in such a mixed bag of fantasy. There is no mention of a polar opening in

At the Earth’s Core,

but Burroughs uses it in the third book,

Tanar of Pellucidar,

to explain the presence of the dastardly Korsars, yo-ho-ho descendants of seventeenth-century Spanish pirates who accidentally sailed over the rim into Pellucidar and have been wreaking havoc there ever since. He also uses the polar opening in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core

to get Tarzan down there to help rescue David Innes, who’s been captured for about the nineteenth time.

At the Earth’s Core,

but Burroughs uses it in the third book,

Tanar of Pellucidar,

to explain the presence of the dastardly Korsars, yo-ho-ho descendants of seventeenth-century Spanish pirates who accidentally sailed over the rim into Pellucidar and have been wreaking havoc there ever since. He also uses the polar opening in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core

to get Tarzan down there to help rescue David Innes, who’s been captured for about the nineteenth time.

Since the interior cooled more slowly than the surface, life started later on Pellucidar, making it “younger” than our world—thus all the prehistoric flora and fauna running riot there. The weird twists life has taken on Pellucidar can be explained by alternate evolution. Life forms from different geologic periods exist simultaneously owing to the absence of the cataclysms that have affected life on the surface. Pellucidar has considerably more land; the proportions of ocean to earth are reversed, so that the land area there is three times greater than above, “the strange anomaly of a larger world within a smaller one!” But the greatest anomaly—which Burroughs never successfully explains—is that time doesn’t exist on Pellucidar. Nobody can tell how long anything takes. It’s supposedly because the sun never sets, but why that would make a difference defies explanation, even though Burroughs insists on it again and again, in book after book. Why this was so important to his conception of Pellucidar is a mystery. But it’s his world, and he can do what he wants.

Other books

The Missing Dog Is Spotted by Jessica Scott Kerrin

Intuition by Allenton, Kate

The Dressmaker's Daughter by Kate Llewellyn

Texas Tornado by Jon Sharpe

Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick

Last Light by C. J. Lyons

The Ravishing One by Connie Brockway

Dragonlance 09 - Dragons of the Hourglass Mage by Weis, Margaret

Flick by Tarttelin,Abigail