Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (36 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

12.01Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

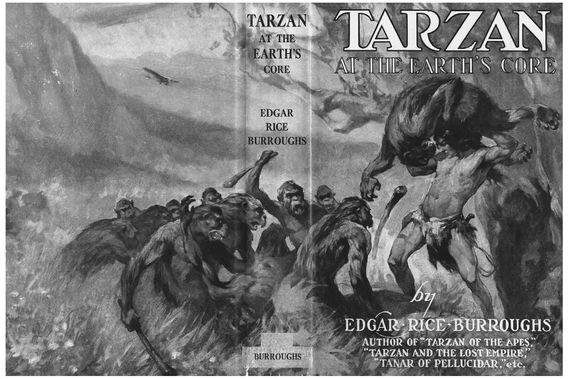

Splendid St. John cover for

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

(© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

(© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

In

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

young Jason Gridley of Tarzana, California, has a special radio that receives signals from Pellucidar. He hears that David Innes has been captured by the Korsars and is being held captive by them, and decides that only Tarzan can free him. Gridley goes to Africa to plead his case, saying that he’s just learned about an opening at the pole that leads to Pellucidar. Tarzan says, hmm, we’ll need a Zeppelin, and just happens to know of an ultralight, ultrastrong metal in nearby mountains that no one else has discovered, so they have a bunch of it mined and go to Germany to construct the airship. As the Zeppelin drops through the polar opening and drifts lower toward Pellucidar’s surface, Tarzan looks approvingly over the landscape and exclaims, “This looks like heaven to me.” As soon as they land, Tarzan decides to take a jungle stroll, and doesn’t reconnect with the others until the book’s end, when almost as an afterthought Innes is sprung from the Korsars’ captivity. Tarzan wasn’t kidding about heaven. Pellucidar is even more unspoiled and primitive than his own jungle at home. And Tarzan loves it:

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

young Jason Gridley of Tarzana, California, has a special radio that receives signals from Pellucidar. He hears that David Innes has been captured by the Korsars and is being held captive by them, and decides that only Tarzan can free him. Gridley goes to Africa to plead his case, saying that he’s just learned about an opening at the pole that leads to Pellucidar. Tarzan says, hmm, we’ll need a Zeppelin, and just happens to know of an ultralight, ultrastrong metal in nearby mountains that no one else has discovered, so they have a bunch of it mined and go to Germany to construct the airship. As the Zeppelin drops through the polar opening and drifts lower toward Pellucidar’s surface, Tarzan looks approvingly over the landscape and exclaims, “This looks like heaven to me.” As soon as they land, Tarzan decides to take a jungle stroll, and doesn’t reconnect with the others until the book’s end, when almost as an afterthought Innes is sprung from the Korsars’ captivity. Tarzan wasn’t kidding about heaven. Pellucidar is even more unspoiled and primitive than his own jungle at home. And Tarzan loves it:

In the first flight of his newfound freedom Tarzan was like a boy released from school. Unhampered by the hated vestments of civilization, out of sight of anything that might even remotely remind him of the atrocities with which man scars the face of nature, he filled his lungs with the free air of Pellucidar, leaped into a nearby tree and swung away through the forest, his only concern for the moment the joyousness of exultant vitality and life. On he sped through the primeval forest of Pellucidar. Strange birds, startled by his swift and silent passage, flew screaming from his path, and strange beasts slunk to cover beneath him. But Tarzan did not care; he was not hunting; he was not even searching for the new in this new world. For the moment he was only living.

This is a beautiful existential moment, in some ways a crystallization of the ethos running throughout all of Burroughs’s work. Tarzan is

somewhere else,

in a place of beauty and adventure, with no noise or bus fumes or electric bills—or responsibilities. Born free …

somewhere else,

in a place of beauty and adventure, with no noise or bus fumes or electric bills—or responsibilities. Born free …

Seconds after this peaceful epiphany,

thwap!

Tarzan is caught in a rope snare, and finds himself hanging upside down, slowly spinning, as a ferocious sabretooth tiger slinks toward him. But even facing death, Tarzan is not afraid. “He had looked upon death in so many forms that it held no terror for him.” He is, however, moved to rare metaphysical introspection. The interior lives of Burroughs’s characters go largely unexplored beyond visceral reactions to whatever the situation is at hand. But here, dangling, about to be a sabre-tooth’s lunch, Tarzan thinks of First and Last Things. It’s the closest to a spiritual creed I’ve found in the Tarzan books and presumably isn’t too far from Burroughs’s own views on these matters:

thwap!

Tarzan is caught in a rope snare, and finds himself hanging upside down, slowly spinning, as a ferocious sabretooth tiger slinks toward him. But even facing death, Tarzan is not afraid. “He had looked upon death in so many forms that it held no terror for him.” He is, however, moved to rare metaphysical introspection. The interior lives of Burroughs’s characters go largely unexplored beyond visceral reactions to whatever the situation is at hand. But here, dangling, about to be a sabre-tooth’s lunch, Tarzan thinks of First and Last Things. It’s the closest to a spiritual creed I’ve found in the Tarzan books and presumably isn’t too far from Burroughs’s own views on these matters:

Tarzan of the Apes would have preferred to die fighting, if he must die; yet he felt a certain thrill as he contemplated the magnificence of the great beast that Fate had chosen to terminate his earthly career. He felt no fear, but a certain sense of anticipation of what would follow after death. The Lord of the Jungle subscribed to no creed. Tarzan of the Apes was not a church man; yet like the majority of those who have always lived close to nature he was, in a sense, intensely religious. His intimate knowledge of the stupendous forces of nature, of her wonders and her miracles had impressed him with the fact that their ultimate origin lay far beyond the conception of the finite mind of man, and thus incalculably remote from the farthest bounds of science. When he thought of God he liked to think of Him primitively, as a personal God. And while he realized that he knew nothing of such matters, he liked to believe that after death he would live again.

Maybe it’s just as well Burroughs kept this sort of thing to a minimum. Tarzan reveals a sort of homegrown deism combined with a vaguely born-again fundamentalism—Thomas Jefferson meets George Bush. Naturally Tarzan doesn’t have to worry about the next life because just as the sabre-tooth strikes,

upsy-daisy

—the Sagoths who had set the snare yank him upward into the trees.

upsy-daisy

—the Sagoths who had set the snare yank him upward into the trees.

We get another glimpse into Burroughs’s attitudes a little farther on from young Jason Gridley, who’s cowering in a tree himself, watching “hundreds” of sabre-tooths slaughtering the game they’ve herded into a deadly roundup circle. Gridley sees in this a development of intelligence on the cats’ part that will lead to their extinction—in their cunning savagery they will eventually wipe out all their prey, and then turn on each other—which leads him to reflect on the future of mankind:

Nor did Jason Gridley find it difficult to apply the same line of reasoning to the evolution of man upon the outer crust and to his own possible extinction in the not far remote future. In fact, he recalled quite definitely that statisticians had shown that within two hundred years or less the human race would have so greatly increased and the natural resources of the outer world would have been so depleted that the last generation must either starve to death or turn to cannibalism to prolong its hateful existence for another short period … What would be next? Gridley was sure that there would be something after man,

who is unquestionably the Creator’s greatest blunder

, combining as he does all the vices of preceding types from invertebrates to mammals, while possessing few of their virtues.

Italics mine. This pessimistic blast comes out of the blue, and has a ring of conviction, all the more so because it seems so uncharacteristic of youthful gung-ho boy scientist Gridley, and feels like a peek behind the curtain into Burroughs himself. Burroughs, among his often wacky enthusiasms, was an early Greenie, ahead of his time in realizing the earth’s fragility. He gave a speech on ecology to a group on Arbor Day, 1922, and discussed conservation issues in a 1930 radio interview, so it was a lifelong concern. And “the Creator’s greatest blunder” business—well, Burroughs carried a weight of bitterness despite his huge popular success. His drive to produce—writing, movie ideas, moneymaking schemes, endless Tarzan spin-offs (among them comic strips, kids’ clubs, Tarzan bread, Tarzan ice cream cups, Tarzan belts, Tarzan bathing suits, Tarzan jungle helmets, Tarzan yoyos, Tarzan candy, etc., etc.) has in it a nervous mania, a constant thirsty seeking for

something

that none of this frantic activity ever managed to quench. In 1934 as his long marriage to Emma crumbled, largely due to her drinking, compounded by his own fondness for the stuff, he decided learning to fly would be just the thing, commenced taking lessons, and bought his own airplane, while also courting Florence Ashton, his second wife-to-be, and scribbling away (well, dictating away) at his nineteenth Tarzan novel,

Tarzan and Jane (Tarzan’s Quest),

which on completion on January 19, 1935, was rejected by

Liberty, Collier’s,

and others before

Blue Book

finally bought and began serializing it in October. It’s interesting that just as the Tarzan manuscript was being rejected, Burroughs turned again to Pellucidar, starting on

Back to the Stone Age

in late January. Possibly just a coincidence, but possible, too, that thinking about Pellucidar was a pleasant retreat for him, more fun than grinding out yet more Tarzan. (He said in a 1938 radio interview that he had originally planned to write only

two

Tarzan novels.)

Back to the Stone Age

marks a further drop in quality. A long flashback to the Tarzan expedition, it relates the adventures of Von Horst, a crew member who becomes separated from the others. However, Von Horst’s story is anything but memorable—just another sequence of near-death scrapes, captures, and escapes, with the usual beautiful prehistoric maiden as a love interest. This manuscript collected rejection slip after rejection slip before being bought by

Argosy

magazine for $1,500 and serialized as

Seven Worlds to Conquer

from January 9 through February 13, 1937, then published in book form under its original title by ERB in September of that year.

something

that none of this frantic activity ever managed to quench. In 1934 as his long marriage to Emma crumbled, largely due to her drinking, compounded by his own fondness for the stuff, he decided learning to fly would be just the thing, commenced taking lessons, and bought his own airplane, while also courting Florence Ashton, his second wife-to-be, and scribbling away (well, dictating away) at his nineteenth Tarzan novel,

Tarzan and Jane (Tarzan’s Quest),

which on completion on January 19, 1935, was rejected by

Liberty, Collier’s,

and others before

Blue Book

finally bought and began serializing it in October. It’s interesting that just as the Tarzan manuscript was being rejected, Burroughs turned again to Pellucidar, starting on

Back to the Stone Age

in late January. Possibly just a coincidence, but possible, too, that thinking about Pellucidar was a pleasant retreat for him, more fun than grinding out yet more Tarzan. (He said in a 1938 radio interview that he had originally planned to write only

two

Tarzan novels.)

Back to the Stone Age

marks a further drop in quality. A long flashback to the Tarzan expedition, it relates the adventures of Von Horst, a crew member who becomes separated from the others. However, Von Horst’s story is anything but memorable—just another sequence of near-death scrapes, captures, and escapes, with the usual beautiful prehistoric maiden as a love interest. This manuscript collected rejection slip after rejection slip before being bought by

Argosy

magazine for $1,500 and serialized as

Seven Worlds to Conquer

from January 9 through February 13, 1937, then published in book form under its original title by ERB in September of that year.

In 1938 Burroughs again returned to Pellucidar, writing the 60,000 words of

Land of Terror

between October and April 1939 while juggling other projects. The story was rejected by every magazine it was sent to. It wasn’t published until 1944, when it appeared as a book under ERB’s own imprint.

Land of Terror

between October and April 1939 while juggling other projects. The story was rejected by every magazine it was sent to. It wasn’t published until 1944, when it appeared as a book under ERB’s own imprint.

Land of Terror

is told by David Innes, who begins by reflecting on how

old

he and Perry are, something that may have been on the author’s mind, since he was sixty-three while writing this amiable nonsense, still churning it out. David is on his way back home to Sari with some of his minions as the story opens, and, wouldn’t you know it, they are attacked as they’re crossing a river, and

captured

. “They were heavy-built, stocky warriors with bushy beards, a rather uncommon sight in Pellucidar where most of the pure-blood white tribes are beardless.” Odder still, “As I looked more closely at my bearded, hairy captors, the strange, the astounding truth suddenly dawned upon me. These warriors were not men; they were women.” One of these he-women comments, “Who wants any more men? I don’t. Those that I have give me enough trouble—gossiping, nagging, never doing their work properly. After a hard day hunting or fighting, I get all worn out beating them after I get home.”

is told by David Innes, who begins by reflecting on how

old

he and Perry are, something that may have been on the author’s mind, since he was sixty-three while writing this amiable nonsense, still churning it out. David is on his way back home to Sari with some of his minions as the story opens, and, wouldn’t you know it, they are attacked as they’re crossing a river, and

captured

. “They were heavy-built, stocky warriors with bushy beards, a rather uncommon sight in Pellucidar where most of the pure-blood white tribes are beardless.” Odder still, “As I looked more closely at my bearded, hairy captors, the strange, the astounding truth suddenly dawned upon me. These warriors were not men; they were women.” One of these he-women comments, “Who wants any more men? I don’t. Those that I have give me enough trouble—gossiping, nagging, never doing their work properly. After a hard day hunting or fighting, I get all worn out beating them after I get home.”

Yes, we’re hearing an echo of

Pantaletta,

with Burroughs indulging in the same role-reversal comedy found in the earlier novel, without superior results. Innes is dragged to Oog, their primitive village, where he encounters “a hairless, effeminate little man,” the husband of Gluck, the leader, she of the “legs like a pro-football guard and ears like a cannoneer.” Away from the women, hubby and a few other men grouse about the women. “‘If I were bigger and stronger than Gluck, I’d beat her with a stick every time I saw her.’ ‘You don’t seem very fond of Gluck,’ I said. ‘Did you ever see a man who was fond of a woman?’ demanded Foola. ‘We hate the brutes.’” David is tossed under guard into a hut, where he meets Zor, a fellow prisoner, who tells him, “‘They have none of the natural sensibilities of women and only the characteristics of the lowest and most brutal types of men,’” another sentiment that might be straight out of

Pantaletta.

A few sleeps later (no one ever knows what time it is in Pellucidar) David, slaving and starving in Gluck’s garden, can’t resist grabbing a tuber and gnawing ravenously on it. This enrages a female sentry, but he manages to coldcock her before she can do him in with her bone knife. Gluck turns up, angered that the sentry tried to beat one of her men, and they struggle—until at last Gluck kills the other woman. David watches it all and is moved to philosophy:

Pantaletta,

with Burroughs indulging in the same role-reversal comedy found in the earlier novel, without superior results. Innes is dragged to Oog, their primitive village, where he encounters “a hairless, effeminate little man,” the husband of Gluck, the leader, she of the “legs like a pro-football guard and ears like a cannoneer.” Away from the women, hubby and a few other men grouse about the women. “‘If I were bigger and stronger than Gluck, I’d beat her with a stick every time I saw her.’ ‘You don’t seem very fond of Gluck,’ I said. ‘Did you ever see a man who was fond of a woman?’ demanded Foola. ‘We hate the brutes.’” David is tossed under guard into a hut, where he meets Zor, a fellow prisoner, who tells him, “‘They have none of the natural sensibilities of women and only the characteristics of the lowest and most brutal types of men,’” another sentiment that might be straight out of

Pantaletta.

A few sleeps later (no one ever knows what time it is in Pellucidar) David, slaving and starving in Gluck’s garden, can’t resist grabbing a tuber and gnawing ravenously on it. This enrages a female sentry, but he manages to coldcock her before she can do him in with her bone knife. Gluck turns up, angered that the sentry tried to beat one of her men, and they struggle—until at last Gluck kills the other woman. David watches it all and is moved to philosophy:

There followed one of the most brutal fights I have ever witnessed. They pounded, kicked, clawed, scratched and bit one another like two furies. The brutality of it sickened me. If these women were the result of taking women out of slavery and attempting to raise them to equality with man, then I think that they and the world would be better off if they were returned to slavery.One of the sexes must rule; and man seems temperamentally better fitted for the job than woman. Certainly if full power over man has resulted in debauching and brutalizing women to such an extent, then we should see that they remain always subservient to man, whose overlordship is, more often than not, tempered by gentleness and sympathy.

At the time Burroughs’s second marriage was in trouble. And despite his tireless effort and the ubiquity of Tarzan (published in thirty-five countries, translated into fifty-eight languages), he still struggled financially; the dark shadows of the coming war were falling as well over his little empire and sales were dropping. Soon paper rationing and shortages would force major cutbacks in his book publications. Perhaps worse, Burroughs was losing faith in himself as a writer. I can think of no other writer of his established popularity whose work was so routinely rejected; and it galled him, too, that he was little more than a joke to the literary community—his would-be peers. All this wore on him, led him into bouts of depression and the dubious fleeting solace of whiskey. In June 1939 Florence underwent major surgery, and, in August of that year, primarily to cut down expenses, they decided to move to Hawaii. Then in November Burroughs suffered several minor heart attacks. Arriving in Hawaii in April 1940, Florence seems to have hated it from the start, possibly since they had left a fairly luxurious Beverly Hills apartment for a scruffy Hawaiian beach shack also semi-inhabited by rats and scorpions. Burroughs made the garage his office. Friends began noticing the tension between him and Florence, along with signs of increased drinking on Burroughs’s part. Still he amassed stacks of pages, knocking off a new Pellucidar short story, “Hodon and O-AA,” in one week during September.

Other books

1944 - Just the Way It Is by James Hadley Chase

Scalpdancers by Kerry Newcomb

Lethal Sin (Dangerous Games Book 1) by Jennifer Bene

Oceans Apart by Karen Kingsbury

The Creature of Black Water Lake by Gary Paulsen

Wild Hearts (Novella) by Tina Wainscott

Cruel Boundaries by Michelle Horst

Dance Upon the Air by Nora Roberts

Romance: Love Dies Hard 2 (Billionaire Romance Series) (Hard to Love) by Cartwright, C.C.