Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (4 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

5.18Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Burnet quotes Moses in regard to what happened next: “The fountains of the great Abyss were broken open.” This was “sixteen Hundred and odd years after the Earth was made.” The culprits were three: the earth standing up so straight and unwavering on its axis, the tender crust covering the watery abyss, and the relentless sun. “Consider the effect that the heat of the Sun would have upon it, and the Waters under it; drying and parching the one, and rarifying the other into vapours.” At the hottest latitudes it would be “continual Summer, the Earth would proceed in driness still more and more, and the cracks would be wider and pierce deeper.” Eventually the sun boiled our earthly egg until it cracked. “When the appointed time was come, that All-wise Providence had design’d for the punishment of a sinful World, the whole fabrick brake, and the frame of the Earth was torn in pieces, as by an Earthquake; and those great portions or fragments, into which it was divided, fell down into the Abysse, some in one posture, some in another.” All fall down. And the world’s face today is the horrible ruin that remained after the floodwaters subsided.

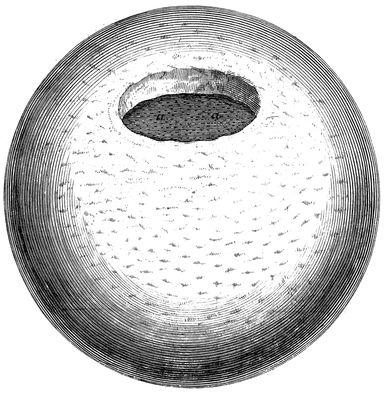

Oddly, given his belief that the sun beating endlessly on equatorial regions put this catastrophe in motion, Burnet places the breaking point near the North Pole, providing a diagram showing an unaccountably regular circular hole in the crust, as if it had been attacked by a cookie cutter rather than blown up by subterranean oceans boiling through ruptured cracks. The proximity to the North Pole makes one wonder if he had been poring over Kircher’s popular

Mundus subterraneus,

which appeared in 1665, sixteen years before Burnet’s

Sacred Theory.

Mundus subterraneus,

which appeared in 1665, sixteen years before Burnet’s

Sacred Theory.

Thomas Burnet understood the earth’s surface as solidified scum atop a liquid interior; as a result of the sun beating down on it, a hole appeared—pictured here. (Reprinted with permission of the Northwestern University Library)

Unfortunately for his career, in the end Burnet seems to have been overly influenced by the new science. In 1692—the same year Halley’s paper about the hollow earth was published in the

Transactions

of the Royal Society—Burnet produced

Archaeologiae philosophicae,

suggesting that the Mosaic account of creation may have simply been an allegory. This is a common liberal interpretation today, of course, but at the time it was just a little too hip for the room. King William took considerable heat over having someone with such scandalous views as his court chaplain and had Burnet fired, ironic since

Archaeologiae philosophicae

was dedicated to William.

Transactions

of the Royal Society—Burnet produced

Archaeologiae philosophicae,

suggesting that the Mosaic account of creation may have simply been an allegory. This is a common liberal interpretation today, of course, but at the time it was just a little too hip for the room. King William took considerable heat over having someone with such scandalous views as his court chaplain and had Burnet fired, ironic since

Archaeologiae philosophicae

was dedicated to William.

Such was the intellectual landscape when Halley proposed his hollow earth theory. Newton’s

Principia

had provided a paradigm of the new science’s accomplishments. But the scientific revolution did not one day simply appear full-blown, Athena out of Zeus’s head. The late seventeenth century was a transitional time. Old theological certainties were now questions to be answered anew, but a belief in God as the great architect of the universe, evident in the work of Kircher and Burnet, continued to be expressed by such paragons of the new science as Newton himself. Indeed, belief in divine Providence led Halley to several of the more remarkable components of his theory.

Principia

had provided a paradigm of the new science’s accomplishments. But the scientific revolution did not one day simply appear full-blown, Athena out of Zeus’s head. The late seventeenth century was a transitional time. Old theological certainties were now questions to be answered anew, but a belief in God as the great architect of the universe, evident in the work of Kircher and Burnet, continued to be expressed by such paragons of the new science as Newton himself. Indeed, belief in divine Providence led Halley to several of the more remarkable components of his theory.

The full title of his 1692 publication was

An Account of the cause of the Change of the Variation of the Magnetical Needle; with an Hypothesis of the Structure of the Internal parts of the Earth; as it was proposed to the

Royal Society

in one of their late Meetings.

An Account of the cause of the Change of the Variation of the Magnetical Needle; with an Hypothesis of the Structure of the Internal parts of the Earth; as it was proposed to the

Royal Society

in one of their late Meetings.

Halley begins with a rather touching mea culpa, saying that “some years since” (in 1683) he had published “a Theory of the Variation of the Magnetical Compass,” proposing “that the Globe of the Earth might be supposed to be one great Magnet, having four Magnetical Poles.” But on reflection, he continues, “I found two difficulties not easie to surmount, the one was that no Magnet I had ever seen or heard of, had more than two opposite poles; whereas the Earth had visibly four, and perhaps more. And secondly, it was plain that those Poles were not, at least all of them, fixt in the Earth, but shifted from place to place, as appeared by the great changes in the Needles direction within this last Century.” He says of these problems, charmingly, “these difficulties had wholly made me despond, and I had long since given over an inquiry I had so little hopes of.” They depressed him and he quit thinking about them.

But then he had a flash: “In accidental discourse, and least expecting it, I stumbled on the following Hypothesis.” He doesn’t tell us what triggered the new thinking. He’s aware that what he’s about to propose may at first blush seem wild and crazy and so he cautions, “If I shall seem to advance any thing that looks like Extravagant or Romantick, the Reader is desired to suspend his censure till he have considered the force and number of the many Arguments which concur to make good so new and so bold a Supposition.” Next he marshals magnetic readings taken between 1580 and 1688 from many parts of the world—London, Paris, the southern Cape of Africa, St. Helena, Cape Comorine in India—to establish the general drift to the west of the magnetic needle over time. “The Direction of the Needle is in no place fixt and constant, tho’ in some [places] it change faster than in others.” So

something

is moving down there to cause this shift, and “this moving thing is very great, as extending its effects from Pole to Pole.” Further, “the motion thereof is not

per saltum

[by fits and starts], but a gradual and regular Motion.” Fine. But, he continues, given “the structure of our

Terraqueous

Globe,” it is hard to imagine that anything can move inside it “without notably changing its Centre of Gravity and the Equilibre of its parts.” It would disturb the rotation of the earth on its axis, “occasion strange alteration in the Sea’s surface, by Inundations and Recesses thereof, such as History has never yet mentioned.” So what’s the answer? That “this moving internal substance be loose and detached from the external parts of the Earth.” If it were attached, “the whole must necessarily move together.” But it doesn’t. The solution—and his great inspiration—“the External Parts of the Globe may well be reckoned as the Shell, and the internal as a

Nucleus

or inner Globe included within ours, with a fluid medium between.”

something

is moving down there to cause this shift, and “this moving thing is very great, as extending its effects from Pole to Pole.” Further, “the motion thereof is not

per saltum

[by fits and starts], but a gradual and regular Motion.” Fine. But, he continues, given “the structure of our

Terraqueous

Globe,” it is hard to imagine that anything can move inside it “without notably changing its Centre of Gravity and the Equilibre of its parts.” It would disturb the rotation of the earth on its axis, “occasion strange alteration in the Sea’s surface, by Inundations and Recesses thereof, such as History has never yet mentioned.” So what’s the answer? That “this moving internal substance be loose and detached from the external parts of the Earth.” If it were attached, “the whole must necessarily move together.” But it doesn’t. The solution—and his great inspiration—“the External Parts of the Globe may well be reckoned as the Shell, and the internal as a

Nucleus

or inner Globe included within ours, with a fluid medium between.”

Placing another sphere, with its own magnetic poles, turning slowly inside our own, solves the problem of the four magnetic poles. The disparity in rotation is slight—“in 365 Revolves the difference is scarce sensible.” But it is enough to account for the gradual westward drift found in magnetic readings.

Alas, there will be scoffers. After urging “all Masters of Ships and Lovers of natural Truths” to continue collecting data and forward it to the Royal Society, he says, almost with a sigh, “in order to explain the change of the variations, we have adventured to make the Earth hollow and to place another Globe within it: and I doubt not but this will find Opposers enough.” He next tackles possible objections—some with more success than others. There is nothing like this in nature. The inner globe would bang against the outer. The seas would leak into it. And, given the metaphysics of the time, even if it were possible, “yet it does not appear of what

use

such an inward Sphere can be of, being shut up in eternal Darkness, and therefore unfit for the Production of Animals or Plants.” (Italics mine.)

use

such an inward Sphere can be of, being shut up in eternal Darkness, and therefore unfit for the Production of Animals or Plants.” (Italics mine.)

He dismisses the first objection by pointing to Saturn surrounded by its rings. The nature of gravity would keep the inner globe from “chocking” against the outer. The seas wouldn’t drain into it because, well, “the Wisdom of the Creator has provided for the Macrocosm by many more ways than I can either imagine or express.” (God still came in handy when needed.) “What Curiosity in the Structure,” he continues, “what Accuracy in the Mixture and Composition of the parts ought not we to expect in the Fabrick of this Globe?” And the very nature of “the Magnetical Matter” might help here. Invoking Newton’s

Principia,

he says that gravity is also such that the particles on the underside of the “Terrestrial parts of our Globe” would over time “molder away or become loose” to “fall in, and with great force descend on the Internal [sphere], unless those particles were of another sort of Matter.” And what might that be? “Why then may we not suppose these said Arches to be lined throughout with a Magnetical Matter, or rather to be one great Concave Magnet, whose two Poles are the Poles we have before observed to be fixt in the Surface of our Globe.” It’s all done by magnets! The magnetical matter would pull everything upward and patch up any holes that might form, like a puncture-proof tire.

Principia,

he says that gravity is also such that the particles on the underside of the “Terrestrial parts of our Globe” would over time “molder away or become loose” to “fall in, and with great force descend on the Internal [sphere], unless those particles were of another sort of Matter.” And what might that be? “Why then may we not suppose these said Arches to be lined throughout with a Magnetical Matter, or rather to be one great Concave Magnet, whose two Poles are the Poles we have before observed to be fixt in the Surface of our Globe.” It’s all done by magnets! The magnetical matter would pull everything upward and patch up any holes that might form, like a puncture-proof tire.

Again he turns to Newton, this time in regard to the relative densities of the earth and moon. Newton had calculated that “the Moon be more solid than the Earth as 9 to 5.” Since the earth consists of the same materials and is so much larger, Halley asks if it isn’t then logical to suppose “four ninths thereof to be Cavity?” As it happens, Newton’s calculation of the moon’s density was one of the few major errors in the

Principia

(the real ratio is 1 to 81), but no one knew that at the time.

Principia

(the real ratio is 1 to 81), but no one knew that at the time.

Now we get to the good part. What possible

use

might these inner spheres have?

use

might these inner spheres have?

He first allows “that they can be of very little service to the Inhabitants of this outward world, nor can the Sun be serviceable to them, either with his Light or Heat.” But he has answers to this objection. What follows next is a neat conflation of science and religion. He says that “it is now taken for granted that the Earth is one of the Planets”—the Copernican view of the universe—“and that they all are with reason supposed Habitable, though we are not able to define by what sort of creatures.” This too was a popular idea at the time. A book published in 1686 by French scientist Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle,

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds,

a chatty account of the latest scientific news that helped further acceptance of the Copernican system, appeared in not one but two English translations in 1688. “I shou’d think it very strange,” he wrote, “that the Earth shou’d be inhabited as it is; and the other Planets shou’d be so entirely desolate and deserted.” He enumerates the vast variety of life on earth, down to those “thousands of small living Creatures” seen through the microscope, and then asks, “After this, can you believe, that Nature, who has been fruitful to Excess as to the Earth, is barren to all the rest of the Planets?”

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds,

a chatty account of the latest scientific news that helped further acceptance of the Copernican system, appeared in not one but two English translations in 1688. “I shou’d think it very strange,” he wrote, “that the Earth shou’d be inhabited as it is; and the other Planets shou’d be so entirely desolate and deserted.” He enumerates the vast variety of life on earth, down to those “thousands of small living Creatures” seen through the microscope, and then asks, “After this, can you believe, that Nature, who has been fruitful to Excess as to the Earth, is barren to all the rest of the Planets?”

This notion of an “abundant Providence,” the idea that creation must be as copious as possible because that would logically be part of the Creator’s plan, was a commonplace in seventeenth-century theology. Halley uses it, seemingly taking inspiration from de Fontenelle to make an argument for a more abundant creation

within

the earth:

within

the earth:

Since we see all the parts of the Creation abound with Animate Beings, as the Air with Birds and Flies, the Water with the numerous varieties of Fish, and the very Earth with Reptiles of so many sorts; all whose ways of living would be to us incredible did not daily Experience teach us. Why then should we think it strange that the prodigious Mass of Matter, whereof this Globe does consist, should be capable of some other improvement than barely to serve to support its Surface? Why may not we rather suppose that the exceeding small quantity of solid Matter in respect to the fluid Ether, is so disposed by the Almighty Wisdom as to yield as great a Surface for the use of living Creatures as can consist with the conveniency and security of the whole.

An inner sphere would provide more room for life.

But, he notes, ever aware of skeptics, some will say there can be no life down there without light “and therefore all this

apparatus

of our inward Globes must be useless.” He admits he doesn’t have a solid response to this one and says, a bit defensively, “To this I answer that there are many ways of producing Light which we are wholly ignorant of,” and offers some possibilities: the medium itself may be “luminous after the manner of our

Ignes fatui.

” This is the Latin term for the phosphorescent light that hovers over swampy ground at night, sometimes known as will-’o-the-wisp. Seems like a stretch. A better possibility comes next: “The Concave Arches may in several places shine with such a substance as invests the Surface of the Sun.” But he does not suggest what the substance may consist of and ultimately falls back on the unknown: “Nor can we, without a boldness unbecoming a Philosopher, adventure to affect the impossibility of peculiar Luminaries below, of which we have no sort of

Idea.

” There may be a source of light down there beyond guessing about up here. Gently parodying the common academic appeal to ancient authority, he adds that “the Poets

Virgil

and

Claudian

have gone before me in this Thought, inlightning their

Elysian Fields

with Sun and Stars proper to those infernal, or rather internal, Regions.” He quotes two lines from book six of the

Aeneid:

apparatus

of our inward Globes must be useless.” He admits he doesn’t have a solid response to this one and says, a bit defensively, “To this I answer that there are many ways of producing Light which we are wholly ignorant of,” and offers some possibilities: the medium itself may be “luminous after the manner of our

Ignes fatui.

” This is the Latin term for the phosphorescent light that hovers over swampy ground at night, sometimes known as will-’o-the-wisp. Seems like a stretch. A better possibility comes next: “The Concave Arches may in several places shine with such a substance as invests the Surface of the Sun.” But he does not suggest what the substance may consist of and ultimately falls back on the unknown: “Nor can we, without a boldness unbecoming a Philosopher, adventure to affect the impossibility of peculiar Luminaries below, of which we have no sort of

Idea.

” There may be a source of light down there beyond guessing about up here. Gently parodying the common academic appeal to ancient authority, he adds that “the Poets

Virgil

and

Claudian

have gone before me in this Thought, inlightning their

Elysian Fields

with Sun and Stars proper to those infernal, or rather internal, Regions.” He quotes two lines from book six of the

Aeneid:

Largior hic campos aether et lumine vestit

Purpureo; Solemque suum sua Sidera norunt.

(As translated by Robert Fitzgerald in 1983)Wider expanses of high air endow

Each vista with a wealth of light. Souls here

Posess their own familiar sun and stars.

Other books

Angelica's Grotto by Russell Hoban

Ruled by Steel (The Ascension Series #3) by S.M. Reine

A Memory in the Black (The New Aeneid Cycle) by Munz, Michael G.

Amethyst by Heather Bowhay

Undisputed Truth: My Autobiography by Tyson, Mike

Front of House: Observations from a Decade on the Aisle by Denise Reich

Peacemaker by C. J. Cherryh

Day One: A Novel by Nate Kenyon

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance by Tanya Anne Crosby, Alaina Christine Crosby

Preacher's Journey by Johnstone, William W.