Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (9 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

2.55Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

During this time in Newport, 1819-1820, he did accomplish one thing, and it was, in its way, a landmark, though one quickly forgotten. He wrote a novel called

Symzonia: Voyage of Discovery.

It bore the byline Captain Adam Seaborn, but is universally attributed to Symmes. Seaborn calls the land he discovers inside the earth Symzonia. Lavish praise is heaped on Symmes throughout (“That profound philosopher, John Cleve Symes”). The novel seems a long, sweet dream by Symmes of what he might find and accomplish if only he were permitted to do so. But it is more than that. According to Victoria Nelson in her 1997

Raritan

article, “Symmes Hole, Or the South Polar Romance,”

Symzonia

was the very first American utopian novel.

Symzonia: Voyage of Discovery.

It bore the byline Captain Adam Seaborn, but is universally attributed to Symmes. Seaborn calls the land he discovers inside the earth Symzonia. Lavish praise is heaped on Symmes throughout (“That profound philosopher, John Cleve Symes”). The novel seems a long, sweet dream by Symmes of what he might find and accomplish if only he were permitted to do so. But it is more than that. According to Victoria Nelson in her 1997

Raritan

article, “Symmes Hole, Or the South Polar Romance,”

Symzonia

was the very first American utopian novel.

All utopian novels ultimately derive from Plato’s

Republic

, but the term comes from Thomas More’s

Utopia

—which means Nowhere—published in 1516. Between More and Symmes, many dozens of utopian fictions and treatises had been inflicted on an imperfect world. A

selective

New York Public Library bibliography lists 153 of them as appearing between 1516 and 1820. But

Symzonia

seems to be the first homegrown American utopian fiction.

Republic

, but the term comes from Thomas More’s

Utopia

—which means Nowhere—published in 1516. Between More and Symmes, many dozens of utopian fictions and treatises had been inflicted on an imperfect world. A

selective

New York Public Library bibliography lists 153 of them as appearing between 1516 and 1820. But

Symzonia

seems to be the first homegrown American utopian fiction.

It wasn’t the first fiction set in subterranean realms. There had been a scattering of these during the eighteenth century, from several countries. The earliest was

Relation d’un voyage du pole arctique au pole antarctique

(1721), which recounts a Kircherean roller-coaster ride on a whaling ship sucked into a vortex somewhere north of Greenland, racing through the watery bowels of the earth from North to South Pole, where an extraordinary island floating under the Antarctic is found. Luxuriant vegetation reigns among warm-water lakes and waterfalls; the voyagers witness battles between polar bears and seals, encounter giant fish, a volcano, a pyramid with fiery reflections, and a structure of white stones before setting sail for the Cape of Good Hope. Another French novel,

Lamekis, ou les voyages extraodinaires d’un egyptien dans la terre interieure

(1734), took its characters to a roomy subterranean world beneath Egypt.

Relation d’un voyage du pole arctique au pole antarctique

(1721), which recounts a Kircherean roller-coaster ride on a whaling ship sucked into a vortex somewhere north of Greenland, racing through the watery bowels of the earth from North to South Pole, where an extraordinary island floating under the Antarctic is found. Luxuriant vegetation reigns among warm-water lakes and waterfalls; the voyagers witness battles between polar bears and seals, encounter giant fish, a volcano, a pyramid with fiery reflections, and a structure of white stones before setting sail for the Cape of Good Hope. Another French novel,

Lamekis, ou les voyages extraodinaires d’un egyptien dans la terre interieure

(1734), took its characters to a roomy subterranean world beneath Egypt.

In 1741 came the first novel of an underworld with real literary merit, Baron Ludvig Holberg’s

Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground.

The preeminent Scandanavian writer of the Enlightenment, Holberg is claimed by both Denmark and Norway as a literary great.

Niels Klim,

first written in Latin, owes a considerable debt to

Gulliver’s Travels

in spirit and shape. Niels enters a cavern and falls toward the center of the earth, thinking as he drops,

Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground.

The preeminent Scandanavian writer of the Enlightenment, Holberg is claimed by both Denmark and Norway as a literary great.

Niels Klim,

first written in Latin, owes a considerable debt to

Gulliver’s Travels

in spirit and shape. Niels enters a cavern and falls toward the center of the earth, thinking as he drops,

I fell to imagining that I was sunk into the subterranean world, and that the conjectures of those men are right who hold the Earth to be hollow, and that within the shell or outward crust there is another lesser globe, and another firmament adorned with lesser sun, stars, and planets. And the event discovered that this conjecture was right.

Instead of falling all the way, he finds himself suspended in orbit. On consideration, he decides that’s fine—as a heavenly body he “would surely move with equal solemnity to a famished philosopher.” But then a flying monster approaches, a menacing griffin a little like the one that gives Dante a ride in the

Inferno.

“So great was my terror that, unmindful of my starry dignity to which I was newly advanced, in that disorder of my soul I drew out my university testimonial, which I happened to have in my pocket, to signify to this terrible adversary that I had passed my academical examination, that I was a graduate student, and could plead the privilege of my university against anyone who should attack me.” Niels’ jaunty insouciance gives the novel considerable charm, though it suffers from the defect common to all utopian fiction: the story repeatedly stops dead in its tracks to explain one or another set of customs. Niels harpoons the griffin and both fall to the planet Nazar below, where he is bothered by a bull and climbs a tree to get away. The “tree” proves to be the wife of the chief magistrate in a nearby city, and Niels finds himself jailed for assault. The creatures are cousin to those in the Forest of Suicides in the

Inferno

—trees with human heads on top and little feet on which they creep about. Nazar is a topsy-turvy utopia, or rather a bunch of them, where prevailing values on the surface are overturned. Niels spends much of the book traveling from country to country, each one devoted to its particular idée fixe. The novel adds Holberg’s voice to those of Montesquieu and Voltaire in their battle against religious fanaticism, the pious persecution and torture it leads to, doing so with humor, as Klim travels round the planet and encounters countries where the authorities cruelly suppress divergent views. The novel was quickly translated into French, English, German, Dutch, and Danish.

Inferno.

“So great was my terror that, unmindful of my starry dignity to which I was newly advanced, in that disorder of my soul I drew out my university testimonial, which I happened to have in my pocket, to signify to this terrible adversary that I had passed my academical examination, that I was a graduate student, and could plead the privilege of my university against anyone who should attack me.” Niels’ jaunty insouciance gives the novel considerable charm, though it suffers from the defect common to all utopian fiction: the story repeatedly stops dead in its tracks to explain one or another set of customs. Niels harpoons the griffin and both fall to the planet Nazar below, where he is bothered by a bull and climbs a tree to get away. The “tree” proves to be the wife of the chief magistrate in a nearby city, and Niels finds himself jailed for assault. The creatures are cousin to those in the Forest of Suicides in the

Inferno

—trees with human heads on top and little feet on which they creep about. Nazar is a topsy-turvy utopia, or rather a bunch of them, where prevailing values on the surface are overturned. Niels spends much of the book traveling from country to country, each one devoted to its particular idée fixe. The novel adds Holberg’s voice to those of Montesquieu and Voltaire in their battle against religious fanaticism, the pious persecution and torture it leads to, doing so with humor, as Klim travels round the planet and encounters countries where the authorities cruelly suppress divergent views. The novel was quickly translated into French, English, German, Dutch, and Danish.

A whimsical sort-of-subterranean English novel,

The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins

by Robert Paltock, published in 1751, is, as a contemporary critic grumped in the

Monthly Review,

“the illegitimate offspring of no very natural conjunction betwixt Gulliver’s travels and Robinson Crusoe; but much inferior to the meaner of these two performances, either as to entertainment or utility. It has all that is impossible in the one, or improbable in the other, without the wit and spirit of the first, or the just strokes of nature and useful lessons of morality of the second.” Paltock probably figured that stealing from two best sellers at once doubled his chances at a hit, and

Peter Wilkins

has a certain mutant appeal. After seducing and marrying a servant girl—there are touches of

Tom Jones

, published two years earlier, as well—Wilkins signs on a ship, is taken as a slave by Portuguese in Angola, escapes with a resourceful black fellow slave, and has many adventures in Africa before stealing a ship with other English refugees.

The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins

by Robert Paltock, published in 1751, is, as a contemporary critic grumped in the

Monthly Review,

“the illegitimate offspring of no very natural conjunction betwixt Gulliver’s travels and Robinson Crusoe; but much inferior to the meaner of these two performances, either as to entertainment or utility. It has all that is impossible in the one, or improbable in the other, without the wit and spirit of the first, or the just strokes of nature and useful lessons of morality of the second.” Paltock probably figured that stealing from two best sellers at once doubled his chances at a hit, and

Peter Wilkins

has a certain mutant appeal. After seducing and marrying a servant girl—there are touches of

Tom Jones

, published two years earlier, as well—Wilkins signs on a ship, is taken as a slave by Portuguese in Angola, escapes with a resourceful black fellow slave, and has many adventures in Africa before stealing a ship with other English refugees.

They become lost sailing south, where the ship, reaching the Antarctic, is inexorably attracted to a black lodestone mountain—the looming shadow of Mercator—and all but Wilkins are swept overboard. He begins exploring in a smaller boat, which is caught in a current and yanked down the drain of a maelstrom, bobbing up into an enormous underground cavern. Coming upon a small island, he sets up housekeeping à la Crusoe. Far luckier than Crusoe, who had only unsexy Friday for company, Wilkins meets one of the locals, a beautiful winged young woman with skin like the down of a swan. They marry, after a fashion, and live together for many years as a happy couple, raising several children, until she decides to visit her family. Wilkins helps the king thwart a plot to overthrow him, asking as reward that slavery be abolished and reading introduced to the peasantry—a little utopian nod here at the end. At the last, his wife dead, Wilkins old, he begins longing for England. Borne aloft, homeward, by winged bearers, he is unceremoniously dropped into the sea when a passing ship fires a cannon at this unlikely sight and frightens them off.

Easily the oddest of these eighteen-century subterranean novels, not to say the creepiest, is Jacques Casanova’s five-volume

Icosameron,

published in 1788 and running to a little over 1,800 pages. The novel recounts the experiences of a teenage brother and sister who fall into the earth’s interior through a watery abyss. There they find an inner world inhabited by many-colored hermaphroditic dwarves called Megamicres, who live in a color-coded social hierarchy with the red ones at the top of the heap. Their primary method of eating consists of sucking on each other’s breasts. They’re also nudists. Edward and Elizabeth promptly rip off their own clothes, declare themselves married, and set about propagating as fast as they can. Each year during their eighty-one-year stay, Elizabeth gives birth to twins, who in turn marry at age twelve and begin having their own twins. Finally Ed and Liz make their way back to London, leaving behind millions of offspring. Not only do they cause a population glut down there, they screw up a previously balanced society in other ways as well, introducing gunpowder and war, among other things.

Icosameron,

published in 1788 and running to a little over 1,800 pages. The novel recounts the experiences of a teenage brother and sister who fall into the earth’s interior through a watery abyss. There they find an inner world inhabited by many-colored hermaphroditic dwarves called Megamicres, who live in a color-coded social hierarchy with the red ones at the top of the heap. Their primary method of eating consists of sucking on each other’s breasts. They’re also nudists. Edward and Elizabeth promptly rip off their own clothes, declare themselves married, and set about propagating as fast as they can. Each year during their eighty-one-year stay, Elizabeth gives birth to twins, who in turn marry at age twelve and begin having their own twins. Finally Ed and Liz make their way back to London, leaving behind millions of offspring. Not only do they cause a population glut down there, they screw up a previously balanced society in other ways as well, introducing gunpowder and war, among other things.

Symzonia

, published in 1820, was the first American hollow earth novel and set the pattern for many that followed, right down to the present. It established the usual structure for such books—the trip to the pole, discovery of a land and people/creatures inside, adventures and revelations while there, and a return home, usually to ridicule and disbelief. Later books described alarming dystopias down there, but

Symzonia

is a voyage into a utopian world—serving as a vehicle for social commentary as well as a 248-page ad for Symmes’ theories. He begins:

, published in 1820, was the first American hollow earth novel and set the pattern for many that followed, right down to the present. It established the usual structure for such books—the trip to the pole, discovery of a land and people/creatures inside, adventures and revelations while there, and a return home, usually to ridicule and disbelief. Later books described alarming dystopias down there, but

Symzonia

is a voyage into a utopian world—serving as a vehicle for social commentary as well as a 248-page ad for Symmes’ theories. He begins:

In the year 1817, I projected a voyage of discovery, in the hope of finding a passage to a new and untried world. I flattered myself that I should open the way to new fields for the enterprise of my fellow-citizens, supply new sources of wealth, fresh food for curiosity, and additional means of enjoyment; objects of vast importance, since the resources of the known world have been exhausted by research, its wealth monopolized, its wonders of curiosity explored, its every thing investigated and understood!

Far from being some pointless ethereal scheme, his reason for going is pragmatic, useful, and filled with the potential for profit. Symmes succinctly expresses the spirit of the times. One by one the great mysteries of the physical world were being figured out, the earth revealing its last geographical secrets. The poles, a few tangled, uncharted jungles here and there, the odd undiscovered island, were all that remained to be explored—or claimed by some country or other. Even the vast expanse of the American continent was filling up at a dizzying rate. Only three states had been added to the original thirteen by 1800, but by 1820 seven more had joined the ranks, with troublesome Missouri to be added in 1821—all of them, with the exception of Maine, carved out of what had been Indian land and wilderness at the time of the American Revolution. Symmes had seen this happening firsthand after the War of 1812, with swarm after swarm of western settlers using St. Louis as their jumping-off point. One way of viewing this—as Symmes clearly did—was as ever-diminishing possibilities for great blue sky opportunity. The earth’s interior promised virgin land, ripe fruit waiting to be plucked, an unclaimed Eden, and no competition.

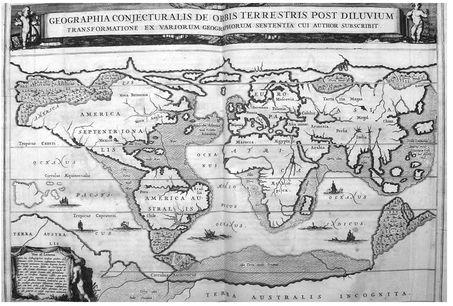

World map from Athansius Kircher’s

Mundus subterraneus

(1665) showing Terra Australis. (Mineralogical Institute, University of Würzburg, Germany)

Mundus subterraneus

(1665) showing Terra Australis. (Mineralogical Institute, University of Würzburg, Germany)

Seaborn has invented a new sort of vessel for his voyage to the South Pole. Certain he will encounter that open polar sea near the verge, he also knows he’ll have to penetrate the “icy hoop” barrier that will come first. His novel steamboat has a specially reinforced frame and powerful slanted paddlewheels capable of churning through the ice. This is a nice Yankee-ingenuity touch. Steamboats were ultramodern craft when Symmes was writing. Robert Fulton’s experiments had introduced the first regularly scheduled steamboat between New York and Albany in 1807, cutting what had been a four-day trip to thirty-two hours. By an interesting coincidence, Symmes had a front-row view of Fulton’s next effort, a steamboat built in Pittsburgh in 1811, which began regular service between New Orleans and Natchez in 1812, routinely chugging past the river forts where Symmes was stationed. But Seaborn’s steamboat also has a design element that’s a bow to the mythical past—no iron in the construction. “I remembered the misfortune of the discoverer SINBAD, whose ship, when he approached the magnetic mountain, fell to pieces,” he explains, so Seaborn uses only “tree-nails” and copper bolts. It’s an odd detail, in that Symmes/Seaborn goes to considerable lengths to seem scientific throughout, and suggests the power this ancient idea apparently still had.

In recruiting his crew, Seaborn wisely neglects to mention that he’s planning a cruise

inside

the earth; instead he signs them on for a three- or four-year term on “a sealing voyage in the South Seas.” Even though Symmes’ real plans related to an expedition to the northern polar opening, he aims for the southern one in the novel. He probably did so because his story would seem less fantastical set there, since less was known about it.

inside

the earth; instead he signs them on for a three- or four-year term on “a sealing voyage in the South Seas.” Even though Symmes’ real plans related to an expedition to the northern polar opening, he aims for the southern one in the novel. He probably did so because his story would seem less fantastical set there, since less was known about it.

Captain James Cook had made a couple of swipes at the Antarctic during his voyages of 1768–1771 and 1772–1775, seeking to prove or disprove the idea of a Terra Australis, the great theoretical southern continent placed on a map by Ptolemy and kept there by succeeding generations of cartographers, though no one had ever seen it. On January 17, 1773, Cook became the first to cross the Antarctic Circle but was stopped by an ice pack without seeing land. He did see one thing that prompted further exploration: seals beyond counting on the forbidding island of South Georgia, a thousand miles east of South America’s southern tip, its dark barren mountains half buried in glaciers, an island Edmond Halley had seen in 1700 while mapping magnetic variation aboard the

Paramour.

18

In the years after Cook’s sighting, slaughter followed knowledge. The pursuit of seals led to more and more incursions into these “inexpressibly horrid regions,” as Cook characterized them in his journal. Despite great hardship and danger, the smell of profit lured the sealers ever deeper into the southern ocean. Whales drew them as well. European and American homes were brightened at night by whale-oil lamps, and the northern whale fisheries were getting fished out. So the rush south was on. But these sealer/whalers weren’t scientific explorers, ready to share the geographical details they were learning; to the contrary, they tried to keep their discoveries secret. The sealers especially, since their dumb wholesale methods—finding an island covered with seals, they would wipe out the entire population before moving on—required locating ever new sealing grounds among the more than two hundred islands strewn east and south of Tierra del Fuego.

19

Paramour.

18

In the years after Cook’s sighting, slaughter followed knowledge. The pursuit of seals led to more and more incursions into these “inexpressibly horrid regions,” as Cook characterized them in his journal. Despite great hardship and danger, the smell of profit lured the sealers ever deeper into the southern ocean. Whales drew them as well. European and American homes were brightened at night by whale-oil lamps, and the northern whale fisheries were getting fished out. So the rush south was on. But these sealer/whalers weren’t scientific explorers, ready to share the geographical details they were learning; to the contrary, they tried to keep their discoveries secret. The sealers especially, since their dumb wholesale methods—finding an island covered with seals, they would wipe out the entire population before moving on—required locating ever new sealing grounds among the more than two hundred islands strewn east and south of Tierra del Fuego.

19

Other books

Secrets in the Shadows by Jenna Black

Mana Mutation Menace (Journey to Chaos Book 3) by Brian Wilkerson

His Beautiful Wench by Dae, Nathalie

Ink & Flowers by J.K. Pendragon

Elysian Dreams by Marie Medina

Frog and Friends by Eve Bunting

New York's Finest by Kiki Swinson

The Seduction of Molly Brown (The Aloha Stories) by Cole, Lynn