Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (44 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

Nevertheless, most people identify with their narrating self. When they say ‘I’, they mean the story in their head, not the stream of experiences they undergo. We identify with the inner system that takes the crazy chaos of life and spins out of it seemingly logical and consistent yarns. It doesn’t matter that the plot is full of lies and lacunas, and that it is rewritten again and again, so that today’s story flatly contradicts yesterday’s; the important thing is that we always retain the feeling that we have a single unchanging identity from birth to death (and perhaps even beyond the grave). This gives rise to the questionable liberal belief that I am an individual, and that I possess a consistent and clear inner voice, which provides meaning for the entire universe.

18

The Meaning of Life

The narrating self is the star of Jorge Luis Borges’s story ‘A Problem’.

19

The story deals with Don Quixote, the eponymous hero of Miguel Cervantes’s famous novel. Don Quixote creates for himself an imaginary world in which he is a legendary champion going forth to fight giants and save Lady Dulcinea del Toboso. In reality, Don Quixote is Alonso Quixano, an elderly country gentleman; the noble Dulcinea is an uncouth farm girl from a nearby village; and the giants are windmills. What would happen, wonders Borges, if out of his belief in these fantasies, Don Quixote

attacks and kills a real person? Borges asks a fundamental question about the human condition: what happens when the yarns spun by our narrating self cause great harm to ourselves or those around us? There are three main possibilities, says Borges.

One option is that nothing much happens. Don Quixote will not be bothered at all by killing a real man. His delusions are so overpowering that he could not tell the difference between this incident and his imaginary duel with the windmill giants. Another option is that once he takes a real life, Don Quixote will be so horrified that he will be shaken out of his delusions. This is akin to a young recruit who goes to war believing that it is good to die for one’s country, only to be completely disillusioned by the realities of warfare.

And there is a third option, much more complex and profound. As long as he fought imaginary giants, Don Quixote was just play-acting, but once he actually kills somebody, he will cling to his fantasies for all he is worth, because they are the only thing giving meaning to his terrible crime. Paradoxically, the more sacrifices we make for an imaginary story, the stronger the story becomes, because we desperately want to give meaning to these sacrifices and to the suffering we have caused.

In politics this is known as the ‘Our Boys Didn’t Die in Vain’ syndrome. In 1915 Italy entered the First World War on the side of the Entente powers. Italy’s declared aim was to ‘liberate’ Trento and Trieste – two ‘Italian’ territories that the Austro-Hungarian Empire held ‘unjustly’. Italian politicians gave fiery speeches in parliament, vowing historical redress and promising a return to the glories of ancient Rome. Hundreds of thousands of Italian recruits went to the front shouting, ‘For Trento and Trieste!’ They thought it would be a walkover.

It was anything but. The Austro-Hungarian army held a strong defensive line along the Isonzo River. The Italians hurled themselves against the line in eleven gory battles, gaining a few kilometres at most, and never securing a breakthrough. In the first battle they lost 15,000 men. In the second battle

they lost 40,000 men. In the third battle they lost 60,000. So it continued for more than two dreadful years until the eleventh engagement, when the Austrians finally counter-attacked, and in the Battle of Caporreto soundly defeated the Italians and pushed them back almost to the gates of Venice. The glorious adventure became a bloodbath. By the end of the war, almost 700,000 Italian soldiers were killed, and more than a million were wounded.

20

After losing the first Isonzo battle, Italian politicians had two choices. They could admit their mistake and sign a peace treaty. Austria–Hungary had no claims against Italy, and would have been delighted to sign a peace treaty because it was busy fighting for survival against the much stronger Russians. Yet how could the politicians go to the parents, wives and children of 15,000 dead Italian soldiers, and tell them: ‘Sorry, there has been a mistake. We hope you don’t take it too hard, but your Giovanni died in vain, and so did your Marco.’ Alternatively they could say: ‘Giovanni and Marco were heroes! They died so that Trieste would be Italian, and we will make sure they didn’t die in vain. We will go on fighting until victory is ours!’ Not surprisingly, the politicians preferred the second option. So they fought a second battle, and lost another 40,000 men. The politicians again decided it would be best to keep on fighting, because ‘our boys didn’t die in vain’.

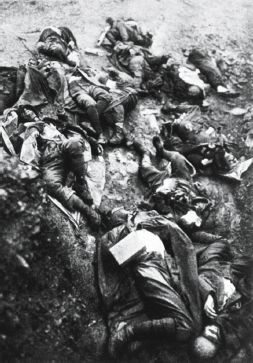

A few of the victims of the Isonzo battles. Was their sacrifice in vain?

© Bettmann/Corbis.

Yet you cannot blame only the politicians. The masses also kept supporting the war. And when after the war Italy did not get all the territories it demanded, Italian democracy placed at its head Benito Mussolini and his fascists, who promised they would gain for Italy a proper compensation for all the sacrifices it had made. While it’s hard for a politician to tell parents that their son died for no good reason, it is far more difficult for parents to say this to themselves – and it is even harder for the victims. A crippled soldier who lost his legs would rather tell himself, ‘I sacrificed myself for the glory of the eternal Italian nation!’ than ‘I lost my legs because I was stupid enough to believe self-serving politicians.’ It is much easier to live with the fantasy, because the fantasy gives meaning to the suffering.

Priests discovered this principle thousands of years ago. It underlies numerous religious ceremonies and commandments. If you want to make people believe in imaginary entities such as gods and nations, you should make them sacrifice something valuable. The more painful the sacrifice, the more convinced people are of the existence of the imaginary recipient. A poor peasant sacrificing a priceless bull to Jupiter will become convinced that Jupiter really exists, otherwise how can he excuse his stupidity? The peasant will sacrifice another bull, and another, and another, just so he won’t have to admit that all the previous bulls were wasted. For exactly the same reason, if I have sacrificed a child to the glory of the Italian nation, or my legs to the communist revolution, it’s enough to turn me into a zealous Italian nationalist or an enthusiastic communist. For if Italian national myths or communist propaganda are a lie, then I

will be forced to admit that my child’s death or my own paralysis have been completely pointless. Few people have the stomach to admit such a thing.

The same logic is at work in the economic sphere too. In 1999 the government of Scotland decided to erect a new parliament building. According to the original plan, the construction was supposed to take two years and cost £40 million. In fact, it took five years and cost £400 million. Every time the contractors encountered unexpected difficulties and expenses, they went to the Scottish government and asked for more time and money. Every time this happened, the government told itself: ‘Well, we’ve already sunk £40 million into this and we’ll be completely discredited if we stop now and end up with a half-built skeleton. Let’s authorise another £40 million.’ Six months later the same thing happened, by which time the pressure to avoid ending up with an unfinished building was even greater; and six months after that the story repeated itself, and so on until the actual cost was ten times the original estimate.

Not only governments fall into this trap. Business corporations often sink millions into failed enterprises, while private individuals

cling to dysfunctional marriages and dead-end jobs. For the narrating self would much prefer to go on suffering in the future, just so it won’t have to admit that our past suffering was devoid of all meaning. Eventually, if we want to come clean about past mistakes, our narrating self must invent some twist in the plot that will infuse these mistakes with meaning. For example, a pacifist war veteran may tell himself, ‘Yes, I’ve lost my legs because of a mistake. But thanks to this mistake, I understand that war is hell, and from now onwards I will dedicate my life to fight for peace. So my injury did have some positive meaning: it taught me to value peace.’

The Scottish Parliament building. Our sterling did not die in vain.

© Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Getty Images.

We see, then, that the self too is an imaginary story, just like nations, gods and money. Each of us has a sophisticated system that throws away most of our experiences, keeps only a few choice samples, mixes them up with bits from movies we saw, novels we read, speeches we heard, and from our own daydreams, and weaves out of all that jumble a seemingly coherent story about who I am, where I came from and where I am going. This story tells me what to love, whom to hate and what to do with myself. This story may even cause me to sacrifice my life, if that’s what the plot requires. We all have our genre. Some people live a tragedy, others inhabit a never-ending religious drama, some approach life as if it were an action film, and not a few act as if in a comedy. But in the end, they are all just stories.

What, then, is the meaning of life? Liberalism maintains that we shouldn’t expect an external entity to provide us with some readymade meaning. Rather, each individual voter, customer and viewer ought to use his or her free will in order to create meaning not just for his or her life, but for the entire universe.

The life sciences undermine liberalism, arguing that the free individual is just a fictional tale concocted by an assembly of biochemical algorithms. Every moment, the biochemical mechanisms of the brain create a flash of experience, which immediately disappears. Then more flashes appear and fade, appear and fade, in

quick succession. These momentary experiences do not add up to any enduring essence. The narrating self tries to impose order on this chaos by spinning a never-ending story, in which every such experience has its place, and hence every experience has some lasting meaning. But, as convincing and tempting as it may be, this story is a fiction. Medieval crusaders believed that God and heaven provided their lives with meaning. Modern liberals believe that individual free choices provide life with meaning. They are all equally delusional.

Doubts about the existence of free will and individuals are nothing new, of course. Thinkers in India, China and Greece argued that ‘the individual self is an illusion’ more than 2,000 years ago. Yet such doubts don’t really change history unless they have a practical impact on economics, politics and day-to-day life. Humans are masters of cognitive dissonance, and we allow ourselves to believe one thing in the laboratory and an altogether different thing in the courthouse or in parliament. Just as Christianity didn’t disappear the day Darwin published

On the Origin of Species

, so liberalism won’t vanish just because scientists have reached the conclusion that there are no free individuals.

Indeed, even Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker and the other champions of the new scientific world view refuse to abandon liberalism. After dedicating hundreds of erudite pages to deconstructing the self and the freedom of will, they perform breathtaking intellectual somersaults that miraculously land them back in the eighteenth century, as if all the amazing discoveries of evolutionary biology and brain science have absolutely no bearing on the ethical and political ideas of Locke, Rousseau and Thomas Jefferson.

However, once the heretical scientific insights are translated into everyday technology, routine activities and economic structures, it will become increasingly difficult to sustain this double-game, and we – or our heirs – will probably require a brand-new package of religious beliefs and political institutions. At the beginning of the

third millennium, liberalism is threatened not by the philosophical idea that ‘there are no free individuals’ but rather by concrete technologies. We are about to face a flood of extremely useful devices, tools and structures that make no allowance for the free will of individual humans. Can democracy, the free market and human rights survive this flood?