Hope Renewed (36 page)

Authors: S.M. Stirling,David Drake

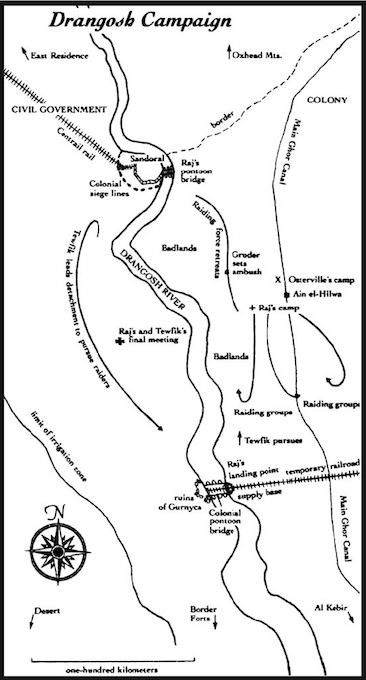

Drangos Map

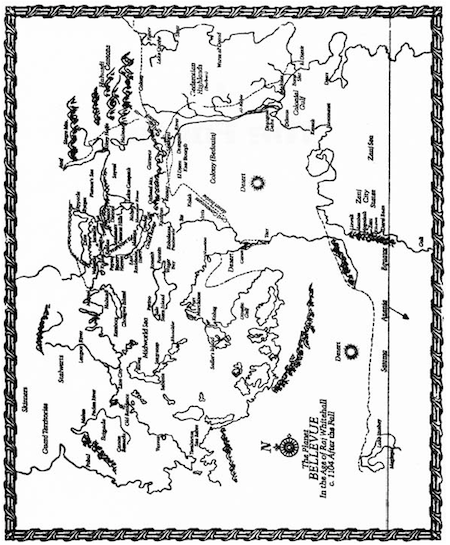

Forge Map 1

To Jan, with love.

And to Steve’s dad, who did a good job.

GET USED TO IT . . .

Jackboots walked over the kitchen floor above Jeffrey and Lucretzia, making the planking creak and sending little trickles of dust down into the cellar. To Jeffrey, the dark basement slowly took on a flat, silvery tone as Center boosted his perceptions.

The voice of Raj echoed in Jeffrey’s mind:

to the right of the door.

Jeffrey’s hand reached out to the knob, moving with an automatic precision that seemed detached and slow. He jerked it backward, and the Land soldier stumbled through. A grid dropped down over his sight, outlining the enemy. A green dot appeared right under the angle of the man’s jaw. His finger stroked the trigger, squeezing.

Crack.

The soldier’s head snapped sideways as if he’d been kicked by a horse. Jeffrey was turning, turning, the pistol coming up. The second soldier was leveling her rifle, but the green dot settled on her throat.

Crack.

The woman fell back and writhed, blood spraying. The soldier behind her was jumping back, out of sight, almost, but the green dot settled on his leg.

Crack.

A scream, as the third soldier tumbled out of sight. The grid outlined a prone figure against the planks of the entranceway, and an aiming point strobed. Jeffrey squeezed the trigger four times. But there was one more soldier, and the bark of the rifle was much deeper than Jeffrey’s pistol. The nickel-jacketed bullet ricocheted, whining around the stones of the cellar like a giant lethal wasp.

Jeffrey tumbled back down the stairs, snapping open the cylinder of his revolver and shaking out the spent brass.

“Christ,” Jeffrey muttered, staggering.

I just killed four human beings.

this is what the world will be, for the rest of your life, Center said.

CHAPTER ONE

Visager

1221 A.F. (After the Fall)

305 Y.O. (Year of the Oath)

Commodore Maurice Farr lifted the uniform cap from his head and wiped at the sweat on his forehead with a handkerchief. He was standing on the liner docks on the north shore of Oathtaking’s superb C-shaped harbor. Behind him were the broad quiet streets of Old Town, running out from Monument Square behind his back. There the bronze figures of the Founders stood, raised weapons in their hands—the cutlasses and flintlocks common three centuries ago. The Empire-Alliance war had ended an overwhelming Imperial victory. The first thing the Alliance refugees had done was swear a solemn oath of vengeance against those who’d broken their ambitions and slaughtered ever yone of their fellows who hadn’t fled the mainland.

After three years in the Land of the Chosen as a naval attaché, Farr was certain of two things: their descendants still meant it, and they’d extended the future field of attack from the Empire to everyone else on the planet Visager. Perhaps to the entire universe.

West and south around the bay ran the modern city of Oathtaking, built of black basalt and gray tufa from the quarries nearby. Rail sidings, shipyards, steel mills, factories, warehouses, the endless tenement blocks that housed the Protégé laborers. A cluster of huge buildings marked the commercial center; six and even eight stories tall, their girder frames sheathed in granite carved in the severe columnar style of Chosen architecture. A pall of coal smoke lay over most of the town below the leafy suburbs on the hill slopes, giving the hot tropical air a sulfurous taste. A racket of shod hooves sounded on stone-block pavement, the squeal of iron on iron and a hiss of steam, the hoot of factory sirens. Ships thronged the docks and harbor, everything from old-fashioned windjammers in with cargoes of grain from the Empire to modern steel-hulled steamers of Land or Republic build.

Out in the middle of the harbor a circle of islands linked by causeways marked the site of an ancient caldera and the modern navy basin. Near it moved the low hulking gray shape of a battlewagon, spewing black smoke from its stacks. His mind categorized it automatically:

Ezerherzog Grukin

, name-ship of her class, launched last year. Twelve thousand tons displacement, four 250-mm rifles in twin turrets fore and aft, eight 175mm in four twin-tube wing turrets, eight 155mm in barbette mounts on either side, 200mm main belt, face-hardened alloy steel. Four-stacker with triple expansion engines, eighteen thousand horsepower, eighteen knots.

The biggest, baddest thing on the water, or at least it would be until the Republic launched its first of the

Democrat

-class in eighteen months.

Farr shook his head.

Enough. You’re going home.

He raised his eyes.

Snow-capped volcanoes ringed the port city of Oathtaking on three sides. They reared into the hazy tropical air like perfect cones, their bases overlapping in a tangle of valleys and folds coated with rain forest like dark-green velvet. Below the forest were terraced fields; Farr remembered riding among them. Dusty gravel-surfaced lanes between rows of eucalyptus and flamboyants. A little cooler than down here on the docks; a little less humid. Certainly better smelling than the oily waters of the harbor. Pretty, in a way, the glossy green of the coffee bushes and the orange orchards. He’d gone up there a couple of times, invited up to the manors of family estates by Chosen navy types eager to get to know the Republic’s naval attaché. Not bad oscos, some of them; good sailors, terrible spies, and given to asking questions that revealed much more than they intended.

Also, that meant he got a travel pass for the Oathtaking District. There were some spots where a good pair of binoculars could get you a glimpse at the base if you were quick and discreet. Nothing earthshaking, just what was in port and what was in drydock and what was building on the slipways. Confirming what Intelligence got out of its contacts among the Protégé workers in the shipyard. That was how you built up a picture of capabilities, bit by bit. He’d been here three years now, he’d done a pretty good job—gotten the specs on the steam-turbine experiments—and it was time to go home.

For more reasons than one. He dropped his eyes to the man and woman talking not far away.

What did I ever see in him? Sally Hosten thought.

Her husband—soon to be ex-husband—stood at parade rest, hands clasped behind his back. Karl Hosten was a tall man even for one of the Chosen, broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted, as trim at thirty-five as he had been twelve years ago when they married. His face was square and so deeply tanned that the turquoise-blue eyes glowed like jewels by contrast; his cropped hair was white-blond. He wore undress uniform: gray shorts and short-sleeved tunic and gunbelt.

“This parting is not of my will,” he said in crisp Chosen-accented Landisch.

“No, it’s mine,” Sally agreed, in English.

She’d spoken Landisch for a long time, her voice had been a little rusty when she went to the Santander embassy to see about getting her Republican citizenship back. She’d met Maurice there. And she didn’t intend to speak Karl’s language again, if she could help it.

“Will you not reconsider?” he said.

Twelve years together had made it easy for her to read the emotions behind a Chosen mask-face. The sorrow she sensed put a bubble of anger at the back of her mouth, hard and bitter.

“Will you give John back his children?” she said.

A brief glance aside showed that her son John wasn’t nearby anymore. Where . . . twenty feet or so, bending over a cargo net with another boy of about the same twelve years. Jeffrey Farr, Maurice’s son.

Karl Hosten stiffened and ran a hand over his stubbled scalp. “The law is the law; genetic defects must be—”

“A clubfoot is not a genetic defect!” Sally said with quiet deadliness. “It’s a result of carriage during pregnancy”—a spear of guilt stabbed her—”which can be, was, corrected surgically. And you didn’t even

tell

me you were having him sterilized in the delivery room. I didn’t find out until he was eleven years old!”

“Would you have been happier if you knew? Would he?”

“How happy would he be when he found out he couldn’t be Chosen?”

Karl swallowed and looked very slightly away.

He is my son too,

he didn’t say. Aloud: “There are many fine careers open to Probationers-Emeritus. Johan is an intelligent boy. The University—”

“As a

Washout

,” Sally said, using the cruel slang term for those who failed the exacting Trial of Life at eighteen after being born to or selected for the training system. It was far better than Protégé status, anything was, but in the Land of the Chosen . . .

“We’ve had this conversation too many times,” she said.

Karl sighed. “Correct. Let us get this over with.”

She looked around. “John!”

John Hosten felt prickly, as if his own skin were too tight and belonged to somebody else. Everyone had been too quiet in the steamcar, after they picked him up at the school. He’d already said good-bye to his friends—he didn’t have many—and packed. Vulf, his dog, was already on board the ship.

I don’t want to listen to them fight,

he thought, and began drifting away from his mother and father.

That put him near another boy about his own age. John’s eyes slid back to him, curiosity driving his misery away a little. The stranger was skinny and tall, red-haired and freckled. His hair was oddly cut, short at the sides and floppy on top, combed—a foreigner’s style, different from both the Chosen crop and the bowl-cut of a Proti. He wore a thin fabric pullover printed in

bizarre

colorful patterns, baggy shorts, laced shoes with rubber soles, and a ridiculous looking billed cap.

“Hi,” he said, holding out a hand. Then: “Ah,

guddag.

”

“I speak English,” John said, shaking with the brief hard clamp of the Land. English and Imperial were compulsory subjects at school, and he’d practiced with his mother.

The other boy flexed his fingers. “Better’n I speak Landisch,” he said, grinning. “I’m Jeffrey Farr. That’s my dad over there.”

He nodded towards a tall slender man in a white uniform who was standing a careful twenty meters from the Hosten party. John recognized the uniform from familiarization lectures and slides: Republic of Santander Navy, officer’s lightweight summer garrison version. It must be Captain Farr, the officer Mom had been seeing at the consulate about the citizenship stuff.

I wish she’d tell me the truth. I’m not a little kid or an idiot,

he thought. That wasn’t the only reason she was talking to Maurice Farr so much. “John Hosten, Probationer-hereditary,” he replied aloud.

A Probationer-hereditary was born to the Chosen and automatically entitled to the training and the Test of Life; only a few children of Protégés were adopted into the course. Then he flushed. He wasn’t going to be a Probationer long, and he could never have passed the Test, not the genetic portions. Not with his foot. He couldn’t be anything but a Washout, second-class citizen.

“You don’t have to worry about all that crap any more,” Jeffrey said cheerfully, jerking a thumb over his shoulder at the liner

Pride of Bosson.

“We’re all going back to civilization.”

The flag that fluttered from her signal mast had a blue triangle in the left field with fifteen white stars, and two broad stripes of red and white to the right. The Republic of Santander’s banner.

John opened his mouth in automatic reflex to defend the Land, then closed it again. He was going to Santander himself. To live.

“Ya, we’re going,” he said. They both looked over towards their parents. “Your mother?”

“She died when I was a baby,” Jeffrey said.

There was a crash behind them. The boys turned, both relieved at the distraction. One of the steam cranes on the

Bosson

’s deck had slipped a gear while unloading a final cargo net on the dock. The Protégé foreman of the docker gang went white under his tan—he’d be held responsible—and turned to yell insults and complaints up at the liner’s deck, shaking his fist. Then he turned and whipped his lead-weighted truncheon across the side of one docker’s head. There was a sound like a melon dropping on pavement; the docker’s face seemed to distort like a rubber mask. He fell to the cracked uneven pavement with a limp finality, as if someone had cut all his tendons.

“Shit,” Jeffrey whispered.

The foreman made an angry gesture with his baton, and two of the dockers took their injured fellow by the arms and dragged him off towards a warehouse. His head was rolled back, eyes disappeared in the whites, bubbles of blood whistling out of his nose. The foreman turned back to the ship and called up to the seamen on the railing, calling for an officer. They looked back at him for a moment, then one silently turned away and walked towards the nearest hatch . . . slowly.

The gang instantly squatted on their heels when the foreman’s attention went elsewhere. A few lit up stubs of cigarette; John could smell the musky scent of hemp mingled with the tobacco. A few smirked at the foreman’s back, but most were expressionless in a different way from Chosen, their faces blank and doughy under sweat and stubble. They were wearing cotton overalls with broad arrows on them, labor-camp inmates’ clothing.

“Hey, that crate’s busted,” Jeffrey said.

John looked. One wood-and-iron box about three meters on a side had sprung along its top. The stencils on the side read

Museum of History and Naturel Copernik.

He felt a stir of curiosity. Copernik was capital of the Land, and the Museum was more than a storehouse; it was the primary research center of the most advanced nation on Visager. He’d had daydreams of working there himself, of finally figuring out some of the mysterious artifacts of the Ancestors, the star-spanning colonizers from Earth. The Federation had fallen over a thousand years ago—it was 1221 A.F. right now—and nobody could understand the enigmatic constructs of ceramic and unknown metals. Not even now, despite the way technology had been advancing in the past hundred years. They were as incomprehensible as a steam engine or a dirigible would be to one of the arctic savages.

“What’s inside?” he said eagerly.

“C’mon, let’s take a look.”

The laborers ignored them; John was in a Probationer’s school uniform, and Jeffrey was an obvious foreigner—an upper-class boy could go where he pleased, and the Fourth Bureau would be lethally interested if they heard of Protégés talking to an

auzlander.

Even in the camps, there was always someplace worse. The foreman was still trading cusswords with the liner’s petty officer.

John grabbed at the heavy Abaca hemp of the net and climbed; it was easy, compared to the obstacle courses at school. Jeffrey followed in an awkward scramble, all elbows and knees.

“It’s just a rock,” he said in disappointment, peering through the sprung panels.

“No, it’s a meteorite,” John said.

The lumpy rock was about a meter across, suspended in an elastic cradle in the center of the crate. It hadn’t taken any damage when the net dropped—unlike a keg of brandy, which they could smell leaking—but then, from the slagged and pitted appearance, it had survived an incandescent journey through the atmosphere. John was surprised that it was being sent to the museum; meteorites were common. You saw dozens in the sky, any night. There must be something unusual about this one, maybe its chemical composition. He reached through and touched it.

“Sort of cold,” he said. Not quite icy, but not natural, either. “Feel it.”

Jeffrey stretched a long thin arm through the crack. “Yeah, like—”

The universe vanished.

Sally looked over her shoulder. Where

was

John? Then she saw him, scrambling over the cargo net with another boy. With Maurice’s son. She opened her mouth to call them back, then closed it.

It’s important that they get along.

Maurice hadn’t made a formal proposal yet, but . . . She turned back.

Karl had his witnesses to either side: his legal children, Heinrich and Gerta, adopted in the fashion of the Chosen. Heinrich was the son of a friend who’d died in an expedition to the Far West Islands; they were dangerous, and the seas between, with their abundant and vicious native life, even more so. The other had been born to Protégé laborers on the Hosten estates and christened Gitana. Karl had sponsored her; she was a bright active youngster and her parents were John’s nurse and attendant valet/bodyguard respectively.