Ida a Novel (21 page)

Authors: Logan Esdale,Gertrude Stein

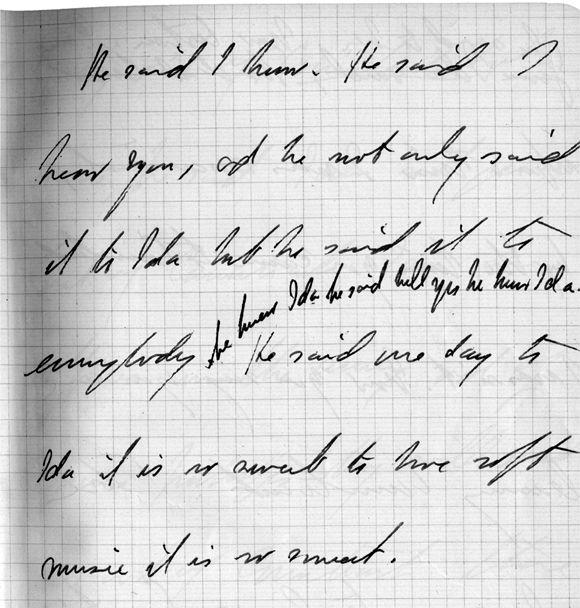

Figure 4: “He said I know. He said I know you, and he not only said it to Ida but he said it to everybody

The text in the fourth notebook is the longest by far, with Stein using more than 140 sheets (both sides) in the 164-sheet notebook. It opens in the fictional city of Bayshore, as the others did, but soon Ida and the narrative begin to move. In October 1937 Stein asked Wilder to send a map of the United States: “I kind of need it to make Ida go on” (see “Selected Letters”). Indeed, references to a multitude of American states—California, Kentucky, Alabama, and so on—appear almost systematic. Brazil, Africa, and France also become part of Ida’s consciousness, and her social geography expands too. In earlier drafts, the narrative had aligned her with one man, Woodward or Harold; now there are many, including Sam Hamlin, Benjamin William, William Benjamin, Joseph, and Frederick.

5

In this notebook, Woodward becomes a powerful man in Washington, a public figure, maybe even the president. People turn to him when they need something done. For instance, in a bizarre episode with Arthur Alexander, who finds “the original dahlia” in Mexico and wants to bring it to America but is denied entrance, Woodward writes to help “but Alexander never had the letter because he had gone off in a boat [. . .]. This is what happens in America and they all laugh” (YCAL 27.547). These Harold-the-Spaniard and dahlia stories refer to the growing nationalism of the late 1930s and the thickening borders between countries. Within the United States, though, Ida moves easily in a light echo of Depression-era drifting.

As in the first two notebooks, the narrative in the latter two is structured in brief vignette chapters, with those in the fourth (almost forty of them) being especially short. Apparently Stein did not give these first-stage manuscripts to Toklas for typing, which means that the narrative she had written over and again did not yet fully satisfy her. Early in 1938, after moving from 27 rue de Fleurus to 5 rue Christine, she set the novel aside to write the play

Doctor Faustus Lights The Lights

and the “Ida” story.

1938–1939

When Stein returned to

Ida

in the summer of 1938, she started by copying from the notebooks in the first stage. Now, however, Ida had become Jenny, and she was sharing the narrative with Arthur; the novel’s new title gives equal billing to both. On two and then five loose sheets, Stein reacquaints herself with the narrative:

IdaArthur and Jenny

A Novel

Chapter one.

Good by now.

Jenny was very careful about Tuesday. She always had to have Tuesday just had to have Tuesday. She had to have Arthur too and that is why the title of this is Arthur and Jenny. Jenny always hesitated before eating. That was Jenny. Jenny She was very young not sixteen yet. She walked as if she was tall, very tall, as tall as any one.

Jenny lived with her great aunt, Where did she live. She lived just on the Well she lived just outside of the a city. outside a city any city, Paris or Chicago or London. She just lived there with not in the city but just outside. (YCAL 26.535)

A Novel

Arthur and Jenny

Chapter I

Good-by now.

Jenny was very careful about Tuesday. She always had to have Tuesday just had to have Tuesday.

Jenny always hesitated before eating. That was Jenny.

Jenny was very young not sixteen yet. She walked as if she was tall, very tall, as tall as any one.

Jenny lived with her great aunt, not in the city but just outside.

Once she was lost that is to say a man followed her and that frightened her so that she was crying when she got back. In a little while it was a comfort to her.

In a little while as her grandfather told her a cherry tree does not look like a pear tree. An old woman told her that she would come to be so much older that not anybody could be older, although said the old woman, there was one who was older. Then her grandfather had told her that a cherry tree never did have to have pears on it nor a pear tree cherries. Her grandfather said there was no use in not saying this. He also said and so everything introduces it or finishes it, and then he said. And not yet.

The old woman told her that her great aunt had had something happen to her oh many years ago, it was a soldier, and then her great aunt had had little twins born to her, and she quietly buried them under a pear tree and nobody knew.

Jenny did not believe her, perhaps it was true perhaps the old woman had told it as it was but Jenny did not believe her. (YCAL 26.535)

On one of the loose sheets from the first stage of composition cited above (see 152), Stein had tested the idea of Ida having a twin: “I am going to have a sister a sister who looks as like me as two peas (not that peas do) and so no one will know which is she and which is me” (YCAL 27.539). This idea returns here with the great aunt and her twins. It is also in Tuesday (Two-s-day); in Jenny being followed; in the old woman’s story being a true copy of the real event (or not); and in the cherry and pear (pair) trees, which in winter, without their leaves, appear similar, though “in a little while” when their fruit comes in they will “not look like” each other.

6

This last example suggests that two entities in a condition of infancy or stasis can appear identical, and that they become distinct by growing or moving.

Ida’s wish for a twin sister returns in the next sequence of “Arthur And Jenny,” 178 sheets arranged in ten chapters. (“Arthur And Jenny” has three primary sequences, the other two being fifty-seven sheets in four chapters and forty-five sheets in six chapters.) Here are the first twelve sheets:

A Novel.Arthur and Jenny.

A Novel

Chapter I

Good-by now.

I

Jenny lived with her great aunt, not in the city but just outside.

She was very young not sixteen yet. She walked as if she was tall, very tall, as tall as any one.

Once she was lost that is to say a man followed her and that frightened her so that she was crying when she was lost. In a little while it was a comfort to her.

Jenny was very careful about Tuesday. She always had to have Tuesday just had to have Tuesday. Tuesday was Tuesday to her.

Jenny always hesitated before eating. That was Jenny.

Her grandfather once told her, and that she could remember, that in a little while a cherry tree does not look like a pear tree. He also always told her that a cherry tree did not have to have pears on it and a pear tree did not have to have cherries on it. Her grandfather often then said. And not yet.

Then there was an old woman who was no relation and she told her that she Jenny would come to be so much older that not anybody could be older, although, said the old woman, there was one who was older.

This old woman once told her that Jenny’s great aunt had had something happen to her oh many years ago, it was a soldier, and then her great aunt had had little twins born to her, and she had quietly, they were dead then, buried them under a pear tree, and nobody knew.

Jenny did not believe the old woman, perhaps it was true perhaps the old woman had told it as it was but Jenny did not believe it, she looked at every pear tree, Jenny did, but she did not believe it.

And now Jenny was eighteen and she lived with her great aunt outside of a city, she had a dog, he was almost blind not from age but from having been born so, and Jenny called him Love, she liked to call him, naturally she did and he liked to come even without her calling him.

It was dark in the morning any morning but since her dog Love was blind it did not make any difference to him.

It is true he was born blind nice dogs often are.

And so Jenny lived with her great aunt. Jenny always talked not very much but she did always talk unless she was alone and she was never alone not even when she was waiting. She always had her dog and though he was blind naturally she could always talk to him.

One day she said listen Love,

7

but listen to everything and listen while I tell you something.

Yes Love, she said to him, you have always had me and I am your little mother yes I am Love, and now you are going to have an aunt, yes you are Love, I am going to have a twin yes I am Love, I am tired of being just one I am going to have a twin and one of us then can go out and one of us can stay in, yes Love yes I am yes I am going to have a twin. You know Love I am like that when I have to have it I have to have it, and I have to have a twin, yes Love.

The house that Jenny lived in was a little on top of a hill, it was not a very pretty house but it was quite a nice one and there was a big field next to it and trees at either end of the field and a path at one side of it and not very many flowers ever because the trees and the grass took up so very much room but there was a good deal of space to fill with Jenny and her dog Love and anybody could understand that she really did want to have a twin. (YCAL 26.534)

Note Stein’s revision of the paragraph about the great aunt’s twins: it now includes a clarifying aside, “they were dead then.” This aside lessens some of the ambiguity surrounding the great aunt’s past that was in the earlier draft. The twins were stillborn and there was no infanticide. Stein’s revisions did not always clarify what she had written in an earlier draft, but here is one example.

The multitude of references and allusions to twins in this opening chapter is suggestive of the larger narrative trajectory. In this stage, Stein is working even more overtly on a romance novel, wherein Jenny will find Arthur and ostensibly become one with him. Stein gives to the romance of lovers as twins a dark frame, however. She is thinking about older (grandfathers and great aunts) and younger (teenage girls) generations and the absence of a middle adult generation. The references to birth are antisentimental, with stillborn twins and Love the dog being blind from birth, not from age as would be more natural. Indeed, as we read above, “[i]t was dark in the morning.”

Readers of

Ida

will recognize this opening chapter as similar to the finished text, albeit with further additions and rearrangement. For one thing, while

Ida

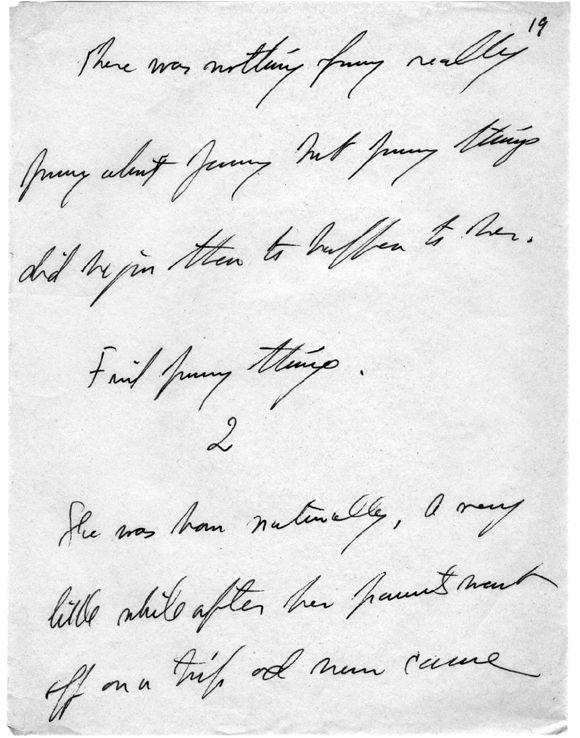

opens with Ida’s birth, and a few paragraphs later we learn that her parents “went off on a trip and never came back,” in “Arthur And Jenny” we wait until the second section of Chapter I (on page 19) for Jenny’s birth and orphanhood (

Figure 5

).

Here is one more substantial transcription from “Arthur And Jenny” (numbered 100–134 in the 178-sheet sequence) for readers to compare with

Ida

:

Chapter III

Sight Unseen.

Arthur knew that Jenny was a name of a woman. He knew that and it made him nervous. She knew it was a name of a twin. What was the other twin’s name. She thought and she thought and she finally decided it would be Winnie which is short for Winnifred, Jenny and Winnie would go very well together.