If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (16 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

William Shakespeare,

King Lear

(1608)

Notice that King Lear doesn’t wash his hand; he merely ‘wipes’ it. This is deeply significant in the history of personal hygiene. The actor playing the first King Lear probably washed himself far less frequently and thoroughly than his medieval predecessors.

The word ‘medieval’ is often – and wrongly – used to mean something primitive, dirty and uncomfortable. This is really unfair to the people of the Middle Ages, where art, beauty, comfort and cleanliness were widely available (at least for those at the top of society). Washing their bodies was an important part of life for prosperous people, and from medieval towns there are numerous records of communal bathing after the Roman model.

More commonly than taking a bath, though, medieval people washed their hands and faces in a basin (the very same word for the much more sophisticated, plumbed-in bowl that you’ll find in your bathroom today). In art, you often see the baby Jesus being sponged down in such a dish. The head of the household usually had his own personal basin, and one of his servants would have had the job of pouring water into it from a

special jug: we know about this because people often left valued basins and jugs to each other in their wills.

It was particularly important to wash your hands just before mealtimes, and the attention you paid to this was a marker of status. Once Cardinal Wolsey dared to dip his fingers in water that had just been used by the king; his presumption in doing so was considered to be outrageously arrogant. This was the kind of minor, intimate but telling detail that led to his downfall.

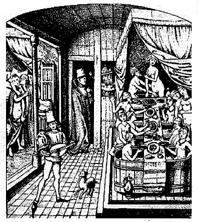

A medieval bathhouse. Its patrons enjoy baths, saunas, drinking and social interaction

But medieval people also immersed their whole bodies in bathwater relatively frequently. A bath was not just for getting clean; it could also be a hugely significant element of ritual purification as well. The ceremony of baptism involved water, priests would wash carefully before taking Mass, and bathing was an important part of the ritual of conferring knighthood. In Britain, this was especially important to the Order of the Garter’s younger sibling, the Order of the Bath. Just before Henry VIII’s coronation in 1509, twenty-six would-be companions of the order had a ritual bath at the Tower of London – denoting ‘future purity of the mind’ – before keeping an all-night vigil in the castle’s medieval chapel.

A knightly bath sounds rather pleasant. The knight’s servant was supposed to hang sheets, flowers and herbs around the wooden tub, and to place in it sponges upon which the knight would sit. The servant then took a basin full of hot, fresh herbal potion in one hand, and used the other to scrub his master’s

body with a soft sponge. The lucky knight was then to be rinsed with rose water, taken out and stood upon his ‘foot sheet’, wiped dry with a clean cloth, dressed in his socks and slippers and nightgown, and sent to bed.

If the knight required a ‘medicinable’ bath (perhaps after jousting), it might have contained hollyhock, mallow, fennel, camomile and ‘small-ache’ (wild water parsley). In his royal palaces, the king had even better baths: as early as 1351 he had ‘two large bronze taps … to bring hot and cold water in’. Henry VIII’s bath at Hampton Court could be found in a room in the Bayne Tower (from

bain

, French for ‘bath’). It was filled from a tap fed by a lead pipe bringing water from a spring more than three miles away. Henry’s engineers performed the amazing feat of passing this pipe beneath the very bed of the River Thames, all this effort being necessary to create, through gravity, the pressure of water to spurt up the height of the two floors to the royal bathroom. The bath itself was made of wood, round like a barrel cut in half and lined with a linen sheet to stop the king from getting splinters in his bottom.

The king may have had his own private bathtub and bathing room, but a great many of his subjects made regular visits to public bathhouses, or ‘stews’. The Crusaders had returned home from the East with reports of the enjoyable Turkish ‘hammams’ they’d visited, and in 1162 there were eighteen bathhouses recorded in the London district of Southwark alone. They were perhaps called by their colloquial name of ‘stews’ from the ‘stoves’ which heated the water, but alternatively it’s worth noting that fish were bred and kept in ponds likewise called ‘stews’. Medieval Londoners loved water as much as fish.

London’s numerous communal bathhouses were concentrated in Southwark, on the south bank of the river, a district devoted to pleasure and packed with playhouses, bear-baiting pits and gardens. When the water was hot and the steam ready at any particular establishment, boys would run through the

streets shouting out the news and drumming up custom. (They were ordered to refrain from doing so before dawn because it woke everybody up.)

The bathhouses were used by large numbers of men and women

all together

. Bathing was a social experience, just like the sauna is in Nordic culture today. People in the Middle Ages – professional hermits excepted – were used to being in a group, and rarely spent time on their own.

While many bathhouses were respectable institutions offering a useful service to the public, some of them shaded over into houses of ill repute, just as many twenty-four-hour massage parlours do today. A prudish monk who visited a communal bathhouse in the 1390s was less than impressed: he found that ‘in the baths they sit naked, with other naked people, and I shall keep quiet about what happens in the dark’. In medieval songs and stories, taking a bath was often an erotic affair. The dynamic and heroic Sir Lancelot is often offered baths or massages by the various damsels he rescues from distress. Just like his twentieth-century equivalent, James Bond, a beautiful and flirtatious girl inevitably appears whenever he’s swimming or bathing.

In literature, it’s sometimes not clear whether a medieval bath is being offered in hospitality or out of feminine designs upon the hero’s body. But in the thirteenth-century story of

The Romance of the Rose

it’s pretty explicit. The ‘Old Lady’ character warns its juvenile hero that

sooner or later you will pass through the flame that burns everyone, and you will bathe in the tub where Venus steams the ladies … I advise you to prepare yourself before you go to bathe, and that you take me for your teacher, for the young man who has no one to instruct him takes a perilous bath.

By the sixteenth century the bathhouses’ reputation had become well and truly tarnished, and they had become synonymous with brothels. In fact, Georgian brothels were often called

bagnios

, even though no actual bathing was happening there any more. Visits to bathhouses were sometimes cited in later medieval divorce cases: like a weekend in Brighton, a person’s spending time at the stews could be taken as evidence that he or she’d been unfaithful.

What was it like, exactly, in a medieval bathhouse? Well, numerous illustrations show rows of individual baths, or even shared communal tubs, in a large room. The heat for the water might conveniently be provided from a baker’s oven next door. Baths themselves were often draped with sheets, partly to make them more comfortable and partly so the sheets could be raised to form a tent-like steam bath. Hot stones might be provided to give extra heat, and spices – cinnamon, liquorice, cumin, mint – to scent the water. The twelfth-century Hildegard of Bingen suggests various combinations of herbs suitable for water to be poured over the head, to be splashed upon rocks in the sauna, to be rubbed directly onto the body, or for a soak. In the bathhouses of thirteenth-century Paris, a steam bath cost two deniers and a slosh in the bathtub itself twice as much. It all sounds delightful: medieval illustrations even show bathers, seated in their tubs, eating meals served on boards laid across the bath.

Perhaps the most sophisticated water systems were to be found in monasteries. Monks were immensely keen on bathing too; it was just they liked to make it single-sex and do it in ascetic cold water rather than hot steam. (A monk named Aldred, chronicler of Fountains Abbey, found it helpful to sit in cold water up to his neck whenever he was plagued by ‘worldly thoughts’.) The monks of Canterbury were mysteriously exempted from the Black Death in 1348–50. What was chalked up at the time to superior praying power may well have been their hyper-efficient plumbing. The monks had five settling tanks to clear the water feeding their frater, scullery and kitchen, bakehouse, brewhouse and guest hall, as well as lavers or fountains trickling into basins for hand-washing.

But many medieval people couldn’t afford the bathhouse. And even if they could, their unwashable fur, leather or woollen clothes were seldom as clean as their skin.

The best way to keep clothes clean was to brush them. A book of advice for young men training as body servants gives these recommendations for robes: ‘brush them cleanly, with the end of a soft brush’, and never let ‘woollen cloth nor fur pass a sennight [a seven-night, a week] unbrushed & shaken’.

The medieval household manual

Le Ménagier de Paris

(1392) gives various recipes for getting rid of fleas, such as scattering a room with alder leaves or attempting to trap the insects on slices of bread smeared with glue. Fleas were particularly hard to remove from furs, but infested garments could be ‘closed up and shut away, as inside a chest tightly strapped, or in a bag tied up securely and squeezed’. Then the fleas should ‘quickly perish’. There was an important social distinction between being afflicted by lice as opposed to fleas. Fleas were almost unavoidable; everyone had them. But to ‘be lowsie’ was an indicator of poor personal hygiene. According to the Georgian entomologist Thomas Muffet, lice were an embarrassing disgrace. (Mr Muffet was the father of the Little Miss Muffet who finds the spider beside her in the nursery rhyme.)

Around 1500, though, something fundamental in society shifted, and the practice of bathing entered into two hundred years of decline and neglect. The bathhouses of London were finally closed down for good in 1546 by Henry VIII. This was done with a flourish and sense of occasion: the stews ‘were by Proclamation and Sound of Trumpet, supress’d, and the Houses let to People of Reputation and Honest calling’.

So began the two ‘dirty’ centuries, from about 1550 to around 1750, during which washing oneself all over was considered for the greater part to be weird, sexually arousing or dangerous. For the few people who could afford to have them at home, baths became medicinal, rather than cleansing, in purpose.

Why did this happen? For a start, many holy wells and baths were closed down in the Reformation because worshipping the saints to whom they were dedicated had become idolatrous and illegal; their secondary purpose of keeping clean was a casualty of this. Bathing also declined because of fears that water spread illness, especially the new and frightening disease of syphilis. As cities grew, it became harder and harder to maintain a supply of clean water. People became increasingly concerned that polluted bathwater might penetrate their skin or gain access to their bodies through their orifices. Sir Francis Bacon’s instructions illustrate how the Tudors and Stuarts believed that they needed to defend their bodies against water:

First, before bathing, rub and anoint the Body with Oil, and Salves that the Bath’s moistening heat and virtue may penetrate into the Body, and not the liquor’s watery part.

A description of the nasty things that lurked in a common bathing pool makes such precautions understandable:

Mad and poison’d from the Bath I fling

With all the Scales and Dirt that around me cling:

Then looking back, I curse that Jakes obscene;

Whence I come sullied out who enter’d clean.

Hot water might even open up the pores in your skin so that the evil ‘miasma’ of the air could enter, bringing sickness with it.

To say that bathing fell out of fashion, though, is not to say that people positively enjoyed being dirty or that they had no concept of cleanliness. It was simply different in scope. Another Tudor health writer recommended that people should dress of a morning but then wash their faces with extreme care, even opening their eyes under water to remove ‘the gum and foulness of the eye-lids that do there stick’. An unpleasant personal odour was still worthy of mention and disparagement. The ‘evil smells’ and ‘displeasant airs’ of Anne of Cleves caused Henry VIII to be unable to consummate his fourth marriage.

In the Tudor or Stuart concept of hygiene, clean underwear played an important part. The wearing of clean linen next to the skin was considered essential in the ‘dirty’ centuries. People thought it was dangerous to immerse their bodies in water but perfectly safe to use linen to absorb the body’s juices, and then to wash the linen regularly.