If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (17 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

In fact, a show of brilliant white linen at the collar and cuffs was important to publicise the cleanliness of your body – and, by implication, the purity of your mind. To the Elizabethan George Whetstone, in his

Heptameron of Civil Discourses

(1582), a woman with dirty linen ‘shall neither be praised of strangers, nor delight her husband’. Spotlessness of the visible outer clothes was extremely important, as proved by the list of linen possessed by the seventeenth-century headmaster of Westminster School. He had only two shirts but fifteen pairs of cuffs. Natural linen is a grey colour, and a great deal of effort is involved in bleaching it to a sparkling white. So, as well as attesting to virtue, to wear white also signified status and wealth.

How did the Tudors wash their underclothes? The first job was to make ‘lye’, or caustic soda, the main detergent. This was done by dribbling water through ash from a fire that had been collected in a wooden tub with a hole in the bottom. The water was passed through the ash again and again, absorbing its chemicals and growing stronger each time. Dirty linen was then soaked in the lye to loosen the dirt, a stage analogous to the pre-wash in a modern washing machine. The receptacle used for soaking, a big wooden tub, was called the ‘buck’. (Hence the name for the laundry tub’s smaller sibling, the ‘bucket’.)

A more concentrated stain-remover was to be found in the form of urine. Hannah Woolley in 1677 gave these instructions ‘to get Spots of Ink out of Linen Cloth’:

Lay it all night in urine, the next day rub all the spots in the urine as if you were washing in water; then lay it in more urine another night and then rub it again, and so do till you find they be quite out.

Urine remained a prized stain-remover right into the twentieth century. In country houses where a heavy and muddy programme of fox-hunting caused the gentlemen’s scarlet coats to need urgent and nightly attention from the valets, a butler named Ernest King remembered that when coats were truly filthy,

… we would ask the housemaid to save us the contents of the chamber pots, at least a bucketful. It was truly miraculous in getting the dirt out.

One suspects that the gentlemen were not told how their coats had been cleaned.

Next on Tudor laundry day came a vigorous stage of scrubbing the linen with soap and beating the dirt out of it with a wooden bat called a ‘beetle’ (i.e. a tool for ‘beating’). As I discovered when I attempted this, it’s very tempting to thwack the balls of soap about with the bats, and there’s a theory that it was the children of laundresses who invented the sport of cricket. This stage of scrubbing and beating was like the main washing cycle in your own machine at home today.

Henry VIII paid his laundress Anne Harris £10 a year to wash his tablecloths and towels, but out of that sum she had to provide her own soap. The soap used in the laundry involved even more lye, or caustic soda. To make it, lye is boiled with animal fat, a process which makes a truly ghastly smell. In seventeenth-century London, the noxious fumes created by soap-makers formed ‘an impure and thick mist, accompanied with a fuliginous and filthy vapour’ over the city. Soap would often come like jelly in a barrel, though it was also formed into hard balls or blocks.

The soaped linen needed a good rinse and then to be squeezed out (today’s spin cycle). Here a cross-shaped post in the ground was a useful anchor for twisting a rope of linen round and round to wring out the drips. Finally, instead of the tumble drier, clothes and sheets were then laid out on bushes to dry in the sun. Rosemary is ideal, for its sweet smell, and hawthorn is also

extremely effective as its prickles act like little clothes pegs to hold the fabric in place.

All this effort was worth it, not just to wear clean clothes, but to have a clean body, and underclothes performed part of the function of the still non-existent bathroom. A clean shirt ‘today serves to keep the body clean’, wrote a French architect in 1626, ‘more conveniently than could the steam-baths and baths of the ancients, who were denied the use and convenience of linen’.

But he was writing just a few decades before bathing began, in advanced circles, to return to favour once more.

16 – … and Its Resurrection

Slovenliness is no part of religion … cleanliness is indeed next to godliness.

John Wesley, in a sermon on dress, 1786

Why did bathing inch its way back into fashion in the eighteenth century?

There had been people bold enough to brave the dangers of bathing throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but they’d usually been undergoing some kind of medicinal treatment bath under the orders of their doctors. Henry VIII, for example, was prescribed herbal baths for the treatment of his suppurating leg ulcer. A seventeenth-century aristocrat was sometimes prescribed a mineral bath, although his doctor’s instructions give a good idea of the precautions thought necessary:

let the liquor be as warm as you can suffer it when you first go into the bath & have hot ready to pour in as it first cools … drink a draught of warm broth or caudle, keeping yourself from cold for some times after.

And it was also under doctors’ orders that bathing began to make a return to everyday experience. The seventeenth century saw the beginning of a huge upheaval in contemporary medical understanding. With the Enlightenment, the Galenic concept that the human body was made up of the four humours would

gradually become discredited. The perceived risks which went with bathing were much reduced once people stopped believing that water could throw their bodies out of equilibrium.

A Tudor tap from Hampton Court Palace. Did it once fill Henry VIII’s bath?

Additionally, there was a new understanding about the nature of sweat. That a large but largely invisible volume of perspiration comes out of our skins every day was proved by the measurements of the physician Sanctorius, whose works became increasingly widely disseminated. By 1724, an English physician could write that it was ‘now known by everybody’ that washing the body freed the pores of ‘that glutinous foulness that is continually falling upon them’. But hot water was still seen as rather risky. It was cold water which returned to favour first.

So a chilly dip began to be considered beneficial for health. It provided a useful jolt to a sluggish system. A cold bath ‘excites the drowsy spirits’, as Sir John Floyer, author of

The History of Cold Bathing

, put it, and ‘the stupid mind is powerfully excited’. But Floyer had an ulterior motive behind his promotion of cold bathing on medical grounds: he thought that the ceremony of baptism ought to involve complete immersion of the body, as in ancient times, and wished the church would restore the practice.

Immersion in cold water, suggested Joseph Browne’s

Account of the Wonderful Cures Perform’d by the Cold Baths

(1707), could cure a multitude of ills: scrofula, rickets, ‘weakness

of Erection, and a general disorder of the whole Codpiece Economy’. Browne was not alone in thinking that a cold bath would have a welcome effect on a limp libido:

Cold bathing has this Good alone

It makes Old John to hug Old Joan

And gives a sort of Resurrection

To buried Joys, through lost Erection.

Dr Richard Russell, author of a

Dissertation on the Use of Seawater

, thought seawater should be drunk for its properties as an excellent laxative – ‘a pint is commonly sufficient in grown persons, to give three or four sharp stools’ – while his colleague Dr Awsiter revealed that ‘in cases of barrenness I look upon seawater to stand before all other remedies’. Bathing in the sea became a popular Georgian holiday activity, and contributed to the growth of the seaside resorts springing up along England’s south coast.

Given the amazing health benefits supposedly to be found in cold water, the next step for enthusiasts was to bathe in their very own homes. At Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, the Curzon family created a private plunge pool down by their lake (

plate 15

). It formed the lower storey of a fishing pavilion (you stuck your rod out of an open upper window). The less plutocratic took a mini-cold-water plunge in a simple bucket. Horace Walpole, afflicted by gout in his face, relied upon the remedy of dipping his head ‘into a pail of cold water, which always cures it’.

Bathing for everyone did genuinely become less dangerous as water supplies grew cleaner. In the Georgian city, houses of the middling sort began for the first time to receive supplies of uncontaminated piped water. Back in 1582, the Dutchman Peter Morritz had noted the existence of a waterwheel at London Bridge. When the tide was right, it would lift river water to supply people’s houses. But the river was also Elizabethan London’s sewer, and its citizens’ own faeces were being recycled back to them.

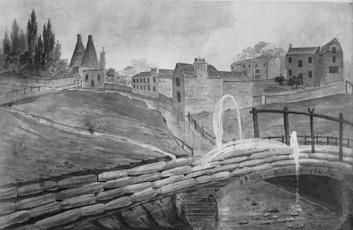

Wooden pipelines bringing water to Georgian London ran along roads like strings of sausages

One of the most impressive engineering achievements in the history of London was the seventeenth-century New River. This artificial waterway, a wiggly forty miles in length, brought fresh water from a Hertfordshire spring into the heart of Islington. A statue of its builder, Sir Hugh Myddleton, still stands proudly in the middle of Upper Street in Islington today. As an engineering achievement, the New River ranks with the Channel Tunnel and the Great Western Railway. The feat of seventeenth-century surveying involved in getting the waterway to follow the correct contours is quite staggering.

From the New River’s head, great rafts of elm pipes were buried beneath the Georgian city’s roads. Sometimes they even ran along the surface, looking like strings of enormous sausages. This was because the pointed end of each hollow trunk slotted into a larger hole at the end of its neighbour. In winter, these surface pipes would be heaped with manure to protect them from frost. Elm was the preferred wood because of its durability in wet conditions, and only in the nineteenth century was it

replaced by iron. These great pipelines marching down London’s roads were tapped at intervals with lead ‘quills’, smaller pipes that ran into the basement kitchens of individual houses.

The whole system worked through gravity, so water pressure was low and often even failed. During the Great Fire of London in 1666, panicking people dug up and punctured the pipes in the streets, ruining the pressure so that the supply quickly fizzled away. In Georgian London, the water supply might be turned on once a week – the ‘water day’ for a particular street – and would run only for a couple of hours. Householders would diligently fill up their cisterns, pots and pans for just as long as the flow lasted. They’d have to purchase extra water from a water-seller roving the streets if they ran out during the week.