IGMS Issue 4 (13 page)

Authors: IGMS

I could barely breathe. I propped myself against the wall and looked up at him.

Max reached across the work table and picked up my laptop. He held it in one hand while staring down at me. The hypercube pattern still flowed on the screen, but Max gave no indication that touching the laptop allowed him to see anything unusual.

"You talk back to me again and I'm gonna shove this thing --" said Max.

"Millions," I said. It was hard to talk.

"What?" said Max. He looked really mad. I was terrified he'd smash the laptop against the table or throw it against the wall.

"What's on that computer is worth millions," I said. A vast understatement.

"Really?" said Max, sneering. He didn't believe me. He casually tossed my laptop to me. "Prove it."

I caught my computer, fumbled and nearly dropped it, then got a good grip on it. The hypercube appeared again and I willed my thundering heart to slow down. I watched the hypercube spin and flicker and steadily lose color, becoming less orange and more white. It was a progress bar of sorts, and as the color faded I "remembered" more and more.

"Prove it!" Max repeated, making me jump. "Prove it right now or I start breaking things."

Marta smiled at me. She was enjoying this.

"Okay," I said. I paused for as long as I could. Almost done. "I'll show you."

Another long pause. To Max and Marta it must have looked like I was just sitting there, staring at nothing. But I knew better. All I needed was a few more moments.

The hypercube turned completely white and then vanished.

Max swore and came at me fast. He reached for me.

"I don't like you, Max," I said. There was a sharp crack as the space he'd occupied became a vacuum and air rushed in to fill the void. He was gone.

Marta stared, frozen in place, still clutching the green jacket. I looked at her and said, "I'm not too fond of you, either." She dropped the jacket and ran.

I stood up, closed my laptop and put it under my arm, and walked carefully out of the lab and down the hall. I felt pretty good right now and didn't want to ruin it by puking. Max had hit me pretty hard.

My extra-dimensional friend had said traveling between universes was beyond my understanding. Maybe he was right. I still had no idea how to do that. But my laptop had been altered somehow into a timeline machine, able to jump itself, me and whatever else I wanted into other universes. And now that the user's manual had been downloaded into my mind, I was ready to do some exploring.

First, however, I was going to take the elevator down to the street. It was unlikely that an alternate universe would happen to have a twenty-two story building in this same spot.

But who knows: maybe Max got lucky.

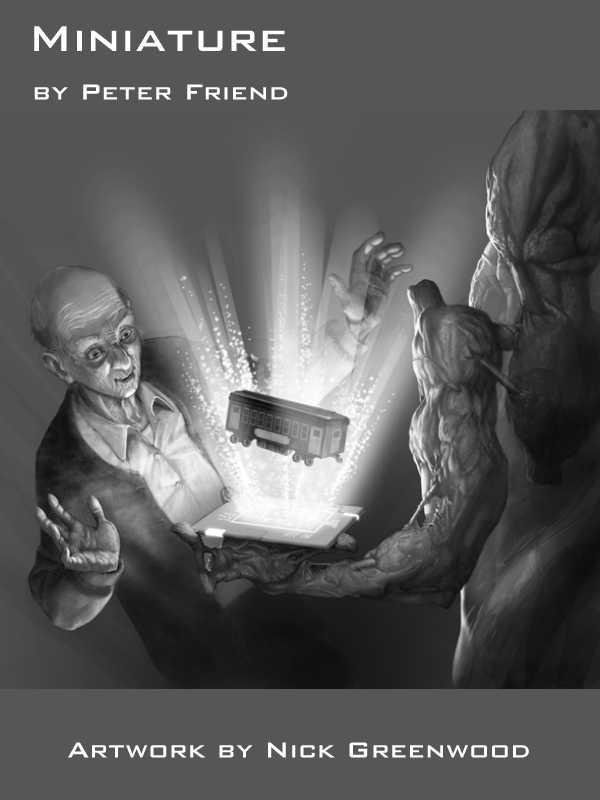

by Peter Friend

Artwork by Nick Greenwood

Three days later it happened again -- knock, knock, knock at Tom's front door, just as he was brushing glue over a papier-mâché hill.

Probably that bloody social services woman again, wanting to drag him along to a Seniors' Sing-Along or some such witless nonsense. Couldn't she get it into her thick head that people came to a retirement village for a bit of peace and quiet? He yanked his door open, ready to give her a good earful.

And stopped. It wasn't her at all; it was one of them alien interviewers, looking twice as ugly in real life as they did on the television. Still, he'd seen worse. He wasn't scared at all, not like some folks.

"Morning," he said, because Ruth had always insisted on being polite to strangers.

"We may talk please, random human," it said, each word in a different voice.

He snorted. "Me? I've never done anything you fellas would be interested in. And I'm busy. This place is chockfull of silly old fools with nothing better to do than gossip all day -- go interview one of them."

That got a reaction, not from the alien but from the other residents, watching through their half-open doors and lace curtains. Served them right.

"You are random," the alien told Tom in three voices, and waved a hundred dollar note at him.

"Well, why didn't you say so before?" he said, because he was always happy to help out folks with more money than brains, no matter what planet they came from. "But I've got glue drying in here, so we'll have to talk while I work."

The alien waddled inside on three stumpy legs. Tom poked his tongue out at his neighbours and closed the door just to spoil their view.

"What is this thing?" the alien asked, pointing its head at the benches -- well, pointing its front end at least, because it didn't seem to have a head as such.

"A model railway. Haven't you fellas seen one before?"

"Model railway," it parroted back to him in his own voice.

For a moment he thought it was making fun of him, then realised this must be how it always talked, by copying people's voices.

"Yeah, like a real railway, but . . . um . . . with models," he said as he spread green sawdust over the sticky hill. "Sorry, don't think I've ever needed to explain it to anyone before. Even little kids get the idea straight away."

The alien pulled out a shiny gizmo from somewhere and suddenly a little black and white movie of an old Wild West train appeared in mid-air, puffing smoke as it rolled past. The alien fiddled with the gizmo and the little train reappeared on Tom's model railway, right on the tracks in front of Pumahara Station, then vanished.

"Understanding," said the alien. "Miniature reality."

Tom laughed. "Yeah, you got the idea. That some kind of hologram projector, huh? Mighty nice. Sell a few billion of them to us dumb humans -- make yourself a fortune."

"Why?" it asked, peering at the rails.

That had Tom stumped for a moment, because if the aliens didn't understand money then why were they handing out hundred dollar notes?

"Why?" it repeated. "This reality, why? True or imagining?"

"Oh, now I get you. Yes, it's all accurate, just like the real places were at the time. See, over here's Pumahara Railway Station, that's where I met my wife-to-be, Ruth, one Saturday morning back in '63. This red brick building is the tea room where I saw her for the very first time -- she was eating a huge pink Lamington and getting coconut all over her face -- I fell in love at first sight. Walked right over to her and told her so, would you believe it? And she raised her pretty little eyebrows, said 'hmmmph,' stood up and boarded her train. Sensible girl."

"Train is human mating ritual?" the alien asked.

"What? No, no. But then again, I suppose for us it was, in a manner of speaking. I came back the following Saturday morning and there she was again, eating another Lamington --chocolate, but just as messy. This time I made a slightly better impression, enough for her to tell me her name was Ruth, and that she visited her parents back in Paenga Kore every Saturday. I mentioned I just happened to be catching the very same train. She didn't believe me for a second, but nevertheless most graciously allowed me to accompany her on board and to sit across the aisle from her. Three hours later we arrived at tiny Paenga Kore Railway Station -- that's the little green-roofed building over there in the far corner. And she invited me to stay for lunch with her parents."

The alien shuffled over and examined the green cardboard railway station intently. "This long ago one journey. You recall such many details."

"Oh, not just the once. We made that same journey nearly every Saturday for over a year while we were courting. That train was slow and noisy and blew soot all over our clothes, but nevertheless . . . sitting there, holding hands and staring out the window without a care in the world . . . it was magical.

"When Ruth passed away a couple of years ago, I wanted something to remember her by. We were married forty years -- and damned good years they were too -- but of all our time together, those train journeys are what I like to remember the most. So I went down to the model shop in the mall and . . . well, to cut a long story short, the result's in front of us. I got a little carried away perhaps -- never intended it to take up most of the lounge -- but that's ok, I don't get many visitors.

"The research is the hardest part. Back in '63 I didn't care tuppence for the train itself, only for the pretty girl on my arm. A couple of them trainspotters down at the model shop told me it was a K Class steam locomotive, and that's confirmed by an old snapshot I had of Ruth next to it. But the carriages aren't so easy to work out. I know they were second-class 56-footer day-cars, almost certainly built in the late thirties. But that's the whole problem -- there were hundreds of them, and by '63 they'd been repaired and redecorated and refitted so many times that . . . well, the model over there on the track, it's close, but it's not quite right."

The alien peered at the carriage and started fiddling with its shiny gizmo again.

"See, here's an old photo of Ruth," he continued. "Isn't she lovely? That shows the seats and a window, and as you can see, the window size doesn't match the model. And here's the only other interior snapshot I've got, the two of us grinning like idiots because we'd just got engaged -- that's a better one of the window and the luggage rack, but it doesn't --"

He stopped. A flickering image of the train carriage floated in mid-air, looking just like his model at first, although larger, and then the windows stretched to match the photos and intricate tiny luggage racks appeared inside the windows.

He crowed in delight. "That's a mighty fine party trick. You can change anything? Can you make that paintwork a darker blue, and not so glossy? Yes, that's it. And I remember the seats were vinyl, imitation leather in shiny green, yes, but a little yellower. The seat legs were chrome, with rusty screws. And the floor was a splotchy white and brown linoleum; Ruth always said it looked like dried bird poop, and made me promise we'd never have linoleum in our home. Oh heck, just listen to me babbling on, I'm the silliest old fool in this whole place. You fellas didn't fly a zillion light years across the universe to listen to this sentimental rot."

"Thank you," said the alien.

The carriage shrank, and dropped into Tom's hands. He only caught it by reflex, expecting just a hologram, but somehow it had become solid, real. He peered in the windows and saw tiny figures of Ruth and himself, exactly like in his snapshot, and all of a sudden he found himself crying.

He wiped his eyes and blew his nose, doubly glad that he'd closed the front door. He hadn't cried since Ruth's funeral. Wouldn't want the neighbours seeing him like this.

"Thank you," he snuffled, then realised the alien had gone.

Gently, he placed the carriage onto the rails, half-expecting it to crumble to dust or disappear, and discovered without surprise that it was perfectly scaled to match the rest of the train -- yeah, that alien knew more about model trains than it had let on, that was for sure. He tried to roll it behind his K Class locomotive, but there was something wrong with the carriage wheels. He turned it over for a closer look and discovered the wheels had no axles and couldn't turn, and that made him laugh and cry and laugh all over again.

"Doesn't matter," he muttered to himself, and softly rubbed the carriage's dark blue paintwork. "The train itself was never the point. The memories are all that ever mattered."