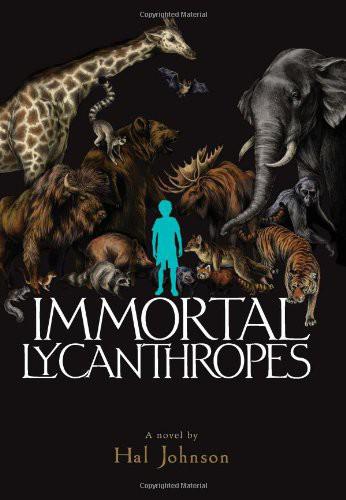

Immortal Lycanthropes

VII. The Conference in the Fortress of the Id

CLARION BOOKS

215 Park Avenue South

New York, New York 10003

Copyright © 2012 by Hal Johnson

Illustrations copyright © 2012 by Teagan White

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Johnson, Hal, 1972–

Immortal lycanthropes / by Hal Johnson; with illustrations by Teagan White.

p. cm.

Summary: A young man discovers that he is part of a secret society of immortal were-creatures bent on hunting one another into extinction.

ISBN 978-0-547-75196-2 (hardcover)

[1. Shapeshifting—Fiction. 2. Supernatural—Fiction. 3. Disfigured persons—Fiction.] I. White, Teagan, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.J63179Im 2012

[Fic]—dc23 2011045438

eISBN 978-0-547-75201-3

v1.0912

for babsey,

light of my life,

and pinkwater,

fire of my loins

“Perchance,” said he, as the five lads lay in the rustling stillness through which sounded the monotonous cooing of the pigeons—“perchance there may be dwarfs and giants and dragons and enchanters and evil knights and whatnot even nowadays. And who knows but that if we Knights of the Rose hold together we may go forth into the world, and do battle with them, and save beautiful ladies, and have tales and gestes written about us as they are writ about the Seven Champions and Arthur his Round-table.”

1.Howard Pyle,

Men of Iron

A shameful fact about humanity is that some people can be so ugly that no one will be friends with them. It is shameful that humans can be so cruel, and it is shameful that humans can be so ugly.

It would be easy to paint a sob story here, but I am trying to remain objective. So: Myron Horowitz, short, scrawny, and hideous, had no friends. The year before, in eighth grade, he had three people he used to eat lunch with. They had perhaps been his friends, but one had moved away over the summer, one had transferred to a private school, and one had gone through puberty and come out popular. Myron Horowitz had not only not gone through puberty, he had not grown an inch in the last five years, not since his accident. People viewing him from behind assumed he was eight years old; from the front, a different set of assumptions came into play. His face had been partially reconstructed, and it was probably very well done, considering what was left to work with. But it was still a twisted, noseless face, and Myron ate alone now. Worse than eating alone, though, was the walk home. At Henry Clay High School, students who took a bus home passed from their locker through the gymnasium to convene in the parking lot; students who walked home took a different route, through the cafeteria and out through a side door, along a wooded path to the sidewalk. Very few students walked home, but Myron did, and so did Garrett Bercelli.

Garrett was not overly large for a freshman, but compared to Myron he was a heavyweight champion. His hands especially were large, and, as they say, sinewy. He probably had reasons for his antisocial behavior, but, frankly, they don’t concern me. He can die and go to hell for all I care, once he has served his purpose in our narrative.

There are disadvantages, I am aware, to beginning our story this fast. Perhaps I should have given Myron a few scenes at home, curled up with his adventure books or bumping elbows with his parents at their cozy breakfast nook. But really, who wants to see that horrible face eat? And anyway, we have places to go. Myron, two years ago, had had a fourth friend, but he died; that part is pretty funny, when you think about it, and if you are heartless, but I barely have time to mention Danny Fitzsimmons. We have places to go. People will turn into animals, and here come ancient secrets and rivers of blood.

It was on a crisp October day in suburban western Pennsylvania, beneath the golden panoply of leaves some people find so charming, that Garrett Bercelli introduced himself to Myron by picking him up and playfully throwing him into a pricker bush. Two days later he cut right to the chase and punched Myron in the stomach. That was a Friday. On Monday, Garrett really went wild; he forbore (so he explained during the course of the beating) to touch Myron’s horrible face, but he pummeled the rest of his body quite mercilessly. At last Myron spat up some blood, and Garrett ran away.

Obviously I cannot literally enter Garrett Bercelli’s head, to observe the shadow parade of his thought processes, but I have investigated the matter enough that I believe I can produce a fairly accurate reconstruction. Garrett ran home, convinced, I believe, that he had killed or maimed poor Myron. This fact in itself did not concern him, but the risk that he would be caught, and punished, was enough to send him hiding in his bed, the way he had as a child. He hadn’t meant to kill Myron, after all, and this should be taken into account. It had all been juvenile high spirits, and things had just gone too far. Garrett could hardly remember the beating, he could just remember the feeling it had given him, the rushing sound in his ears and the reckless abandon. Whether it gave him an erection I do not pretend to know, but let’s assume the answer is yes. The idea that anything as wonderful as the emotions he had undergone in the course of that afternoon could land him in the reformatory was intolerable. He went to school the next day filled with righteous indignation and a healthy dollop of fear (he had, in fact, tried to feign sickness, but his mother would have none of it). Imagine his relief when he saw, in homeroom, Myron at his desk, alive and apparently hale. The relief would have quickly turned to excitement. You may recall the feeling you have had on first discovering that the author of a favorite book had written a dozen more, perhaps under various pseudonyms, the feeling of a world of possibilities opening up. Garrett did not know what that felt like, because, as best I have been able to determine, he had never finished a book not assigned to school, and few of those. As I said, he probably had reasons for being so violent, reasons that do not concern us. But what Garrett felt at that moment was analogous to a reader’s joy. Here was something he could do, something he was good at and could get away with.

“Tuesday, fish sticks; Wednesday, spaghetti; Thursday, meat loaf . . .” the loudspeaker was intoning for the week, when Garrett leaned down a half inch from Myron’s ear.

“If you miss one day,” he hissed, referring either to school or to their meetings after and behind it, “I will kill you.”

Myron was less pleased with the arrangement. His entire body still ached from yesterday’s pummeling, obviously, and there had been blood in his urine. He considered telling his parents, his adoptive parents who had taken him in after the accident. Dr. and Mrs. Horowitz were good people—you don’t adopt a deformed eight-year-old unless you are reasonably unselfish—but it’s no use pretending they understood him. They made a game effort, but a child who never grew an inch from the moment he had been found crawling dazed and torn up along the Maine coast five years ago never really made much sense to them. When Myron looked upset (for example), they cheerfully tended to remind him that at his next birthday he’d be allowed a cell phone, unaware that his true worry was that he’d have no one to call. They were always unaware. I don’t want to have a pity party for Myron Horowitz. He ends up okay, and I have frankly had worse days than his that week. But I have not had many days worse than his worst. Myron was scared, and he was too scared to admit to anyone that he was scared. He had thought about carrying a knife, and had even packed one to bring to school that day, a steak knife from his mother’s kitchen, but it fell out of his knapsack somewhere between home and school, which may have been for the best. Tuesday was a long, slow day; every day at school is a long, slow day, but this one was something special.