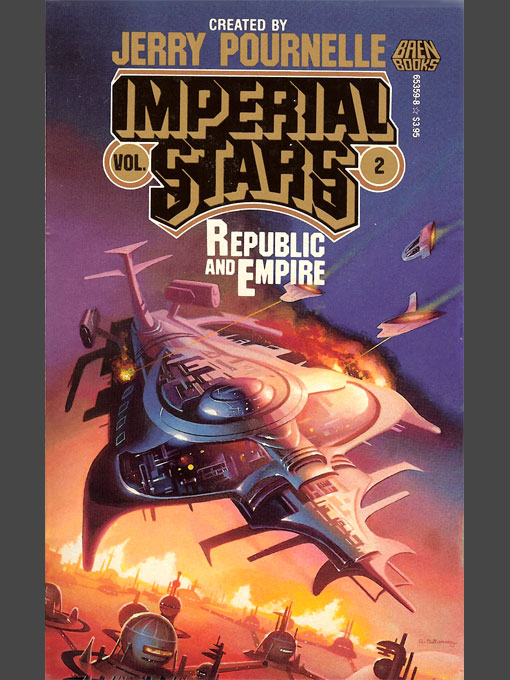

Imperial Stars 2-Republic and Empire

Imperial Stars: Vol. 2

Imperial Stars: Vol. 2Republic and Empire

Jerry Pournelle

DEDICATIONThis is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1987 by Jerry Pournelle

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

260 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10001

First printing, October 1987

ISBN: 0-671-65359-8

Cover art by Alan Gutierrez

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by SIMON & SCHUSTER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N.Y. 10020

For Sir Rodney Hartwell, who keeps alive

the notions of honor in an age that has forgotten.

REPUBLIC AND EMPIRE was written by J.E. Pournelle especially for this volume and appears here for the first time. Published by arrangement with the author and the author's agent, KirbyMcCauley Ltd. Copyright© 1987 by J.E. Pournelle.

OUTWARD BOUND by Norman Spinrad first appeared in

Analog Science Fiction

magazine. It appears here by permission of the author. Copyright © 1964 by Conde Nast Publications.

IN THE REALM OF THE HEART, IN THE WORLD OF THE KNIFE by Wayne Wightman was published originally in the August 1985 issue of

Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine

. Copyright © 1985 by Davis Publications.

DOING WELL BY DOING GOOD by Hayford Peirce was first published in the August 1975 issue of

Analog Science Fiction

magazine. Copyright © 1975 by Condé Nast Publications.

CONSTITUTION FOR UTOPIA by John W. Campbell was first published under the title "Constitution" in the March 1961 issue of

Analog Science Fiction

. Copyright © 1961 by Street & Smith Publications.

MINOR INGREDIENT by Eric Frank Russell was published in the March 1956 issue of

Astounding Science Fiction

. Published here by special arrangement with the author's estate and Scott Meredith Inc. Copyright © 1956 by Street & Smith Publications.

THE TURNING WHEEL by Philip K. Dick first appeared in

Science Fiction Stories #2

in 1954. It appears here by arrangement with the author's agent, Scott Meredith Inc. Copyright © 1987 by Philip K. Dick.

REACTIONARY UTOPIAS by Gregory Benford was first published in the Winter issue of

Far Frontiers

in 1985. It appears here by special arrangement with the author. Copyright © 1985 by Gregory Benford.

THESE SHALL NOT BE LOST by E.B. Cole appeared in the January 1953 issue of

Astounding Science Fiction

. Copyright © 1953 by Street & Smith Publications.

DATA VS. EVIDENCE IN THE VOODOO SCIENCES by J.E. Pournelle first appeared in the October 1983 issue of

Analog Science Fiction

magazine. It appears here by permission of the author and the author's agent, Kirby McCauley Ltd. Copyright © 1983 by Davis Publications.

NICARAGUA: A SPEECH TO MY FORMER COMRADES ON THE LEFT by David Horowitz was first published in

Commentary

in the June 1986 issue. It is published here by special arrangement with the author. Copyright © 1986 by the American Jewish Committee.

CUSTOM FITTING by James White appeared in

Stellar #2

Published by Ballantine Books in 1976 and edited by Judy-Lynn del Rev. It appears here with the permission of the author. Copyright © 1976 by Random House and James White.

CONQUEST BY DEFAULT by Vernor Vinge was first published in the May 1968 issue of

Analog Science Fiction

magazine. It appears here by arrangement with the author. Copyright © 1968 by Conde Nast Publications.

THE SKILLS OF XANADU by Theodore Sturgeon was published in the July 1956 issue of

Galaxy Science Fiction

magazine. Copyright © 1956 by the UPD Corporation.

INTO THE SUNSET by D.C. Poyer first appeared in the July 1986 issue of

Analog Science Fiction

magazine. It is published by permission of the author. Copyright © 1986 by Davis Publications.

SHIPWRIGHT by Donald Kingsbury was originally published in

Analog Science Fiction

magazine in the April 1978 issue. Copyright © 1978 by Conde Nast Publications.

EMPIRE AND REPUBLIC: Crisis and Future by J.E. Pournelle was written especially for this volume and appears here for the first time. Copyright © 1987 by J.E. Pournelle & Associates.

Research for certain nonfiction in this book was supported in part by grants from the Vaughn Foundation and the L-5 Society Promoting Space Development, 1060 E. Elm St., Tucson AZ 85709. Opinions expressed in this book are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Jerry Pournelle

As it was in the past, so shall it be in future: the history of the world has been the struggle of empire and republic. Each has its champions.

It used to be fashionable to say "the Republic of the United States," and our Pledge of Allegiance preserves that language. The name of republic holds magic no less than does the name of empire.

Some of that magic has been lost. In this enlightened time, we are all officially in favor of democracy, and we are pleased to call this the era of democracy. We are taught not only that all democracies are good, but that the worth of a government depends on how democratic it is. The notion that a government can be "good" but not democratic will strike many as bizarre.

It has not always been thus. If we believe, with Thomas Jefferson, that the purpose of government is to assure the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we might do well to recall what Acton said in tracing the history of freedom in Athens:

"Two men's lives span the interval from the first admission of popular influence, under Solon, to the downfall of the State. Their history furnishes the classic example of the peril of democracy under conditions singularly favorable. For the Athenians were not only brave and patriotic and capable of generous sacrifice, but they were the most religious of the Greeks. They venerated the Constitution which had given them prosperity, and equality, and freedom, and never questioned the fundamental laws which regulated the enormous power of the Assembly. They tolerated considerable variety of opinion and great license of speech; and their humanity towards their slaves roused the indignation even of the most intelligent partisan of aristocracy. Thus they became the only people of antiquity that grew great by democratic institutions. But the possession of unlimited power, which corrodes the conscience, hardens the heart, and confounds the understanding of monarchs, exercised its demoralizing influence on the illustrious democracy of Athens. It is bad to be oppressed by a minority, but it is worse to be oppressed by a majority. For there is a reserve of latent power in the masses which, if it is called into play, the minority can seldom resist. But from the absolute will of an entire people there is no appeal, no redemption, no refuge but treason. The humblest and most numerous class of the Athenians united the legislative, the judicial, and, in part, the executive power. The philosophy that was then in the ascendant taught them that there is no law superior to that of the State—the lawgiver is above the law.

"It followed that the sovereign people had a right to do whatever was within its power, and was bound by no rule of right or wrong but its own judgment of expediency. On a memorable occasion the assembled Athenians declared it monstrous that they should be prevented from doing whatever they chose. No force that existed could restrain them, and they resolved that no duty should restrain them, and that they would be bound by no laws that were not of their own making. In this way the emancipated people of Athens became a tyrant, and their government, the pioneer of European freedom, stands condemned with a terrible unanimity by all the wisest of the ancients.

"They ruined their city by attempting to conduct war by debate in the marketplace. Like the French Republic, they put their unsuccessful commanders to death. They treated their dependencies with such injustice that they lost their maritime Empire. They plundered the rich until the rich conspired with the public enemy, and they crowned their guilt by the martyrdom of Socrates.

"The repentance of the Athenians came too late to save the Republic. But the lesson of their experience endures for all time, for it teaches that government by the whole people, being the government of the most numerous and most powerful class, is an evil of the same nature as unmixed monarchy, and requires, for nearly the same reasons, institutions that shall protect it against itself, and shall uphold the permanent reign of law against arbitrary revolutions of opinion."

—John Emerich Edward Dalberg, Lord Acton

"The History of Freedom in Antiquity"

Classical writers spent much time analyzing the forms of government. Machiavelli put it better than most:

"I must at the beginning observe that some of the writers on politics distinguished three kinds of government, viz., the monarchical, the aristocratic, and the democratic; and maintain that the legislators of a people must choose from these three the one that seems most suitable. Other authors, wiser according to the opinion of many, count six kinds of government, three of which are very bad, and three good in themselves, but so liable to be corrupted that they become absolutely bad. The three good ones are those we just named; the three bad ones result from the degradation of the other three, and each of them resembles its corresponding original, so that the transition from the one to the other is very easy.

"Thus monarchy becomes tyranny; aristocracy degenerates into oligarchy; and the popular government lapses readily into licentiousness. So that a legislator who gives to a state which he founds, either of these three forms of government, constitutes it but for a brief time; for no precautions can prevent either one of the three that are reputed good, from degenerating into its opposite kind; so great are in these attractions and resemblances between the good and the evil.

—Niccolo Machiavelli,

The Discourses

This view of government was held universally among writers on history and politics from Aristotle to very nearly the present day. And if we no longer believe that the pure forms of government are inevitably doomed, it is only because we have come to hold, with little evidence, greater faith in democracy than either the ancients or the founding fathers of the United States ever had.

Now, when the classical writers say that a government, whether monarchy, aristocracy, or democracy, is good, this means that the governors put the interest of the state ahead of their own narrow interests; that law, and freedom, and justice, were sovereign.

This, alas, is by no means inevitable in these days of partisan politics; there are politicos in plenty who would chance ruining the state to gain political advantage. Thus, the trend of the U.S. from Republic to Democracy may not deserve the enthusiasm it receives. None of this would have surprised the ancients. To them, human history was no more than the endlessly sad tale of the cycle from tyranny to aristocracy, aristocracy to oligarchy, oligarchy to democracy, and democracy to a chaos ended only by the imposition of an emperor, whose successor will be a tyrant; and on,

per omnia secula seculorem.

However, there might be a remedy to the tragedy of the cycles. Cicero puts it this way:

"When there is a king, everybody except the king has too few rights, and too small a share in what is decided; whereas under an oligarchy, freedom scarcely extends to the populace, since they are not consulted and are excluded from power. When, on the other hand, there is thoroughgoing democracy, however fairly and moderately it is conducted, its egalitarianism is unfair since it does not make it possible for one man to rise above another.

"I am speaking about these three forms of government—monarchy, oligarchy, democracy—when they retain their specific character, not when they are merged and confused with one another. In addition to their liability to the flaws I have just mentioned, each of them suffers from further ruinous defects. For in front of every one of these constitutional forms stands a headlong slippery path to another and more evil one. Thus beneath the endurable, or if you like, lovable Cyrus—to take him as an example—lurks the cruel tyrant Phalaris, influencing him towards the arbitrary transformation of his own nature: for any autocracy readily and easily changes into that sort of tyranny. Then the government of Marseille, conducted by a few leading men, is very close to that clique of the Thirty which once tyrannized Athens. And as for the Athenian democracy, its absolute power turned into rule by the masses; that is to say, into manic irresponsibility.

"You may well ask which of them I like best, for I do not approve of any of them when it is by itself and unmodified: my own preference is for a form of government which is a combination of all three."

—Cicero, "Dialogues on Government"