In Amazonia (11 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

Within a few years of the families' arriving and the sawmill starting up, it became clear that the valuable resources at the mouth of the riverâanimal skins and timber particularlyâwould soon be exhausted. Moreover, the difficulty of communicating among expanding Igarapé Guariba, Viega's upstream cattle post, and the property on the Rio Preto had become a source of considerable frustration for the landowner. Above the waterfall, beyond the the pirizal, hunters reported an upstream forest well-stocked with valuable hardwoods and animals. To get there, hunters would spend hours crossing the swampy lake, pushing and dragging their unladen canoes. On the way back several days laterâif everything went according to planâthey would have salted meat strapped to their backs or be carting sacks of seeds or fruit. The forest, although productive and desired, was a largely non-functional source of value.

Raimundo Viega was proactive and thoroughly instrumental in the face of this dilemma. He organized the men of Guariba into teams. He handed around cane-liquor, gave his orders, and, in the most elaborate accounts, climbed a large tree to supervise the work.

Benedito Macedo and the other men broke through the waterfall. On the far side, they were faced with densely packed barriers of aninga and pirÃ. Slowly, with axes, hoes, and machetes, they dug out a narrow channel, maybe 4 to 6 feet wide, all the time enduring insects and the threat of larger animals. And, from his vantage point high above the flat landscape, Raimundo Viega kept them on track for the forest in the distance.

For close to ten years, the digging in Igarapé Guariba continued during the lean, dry summer months. Once the headwaters had been breached and the lago had been opened, the huge volumes of water that enter the northern channel of the Amazon estuary with the twice-daily tides rapidly swept soil and vegetation out into the main riverâinto what people here, in poetic recognition of its vastness, call the

rio-mar

, the river-sea. Without a definable watershed and surrounded by land too flat for a drainage area, the Rio Guariba is a long, narrow inlet, repeatedly scoured by the erosive tidal action of the Amazon. With the barrier of the waterfall removed and a passage opened into the low-lying

campo

, the flood of the Amazon poured into the upstream basin,

excavating and widening the main channel. Today, people recline on the wooden boards of their front porches and watch as fallen trees, big chunks of riverbank, and islands of grass flow evenly out to sea on the tide.

Transport to the upstream forest soon became possible not only by canoe, but also by sail and motorboat. And it was then that the residents of Igarapé Guariba, independently of the Old Man, and often without his knowledge, began to cut their own routes. They formed communal work teams, and they maintained the openings by taking his buffalo and driving them repeatedly through the new gullies. Two of the Macedo brothers who had done much of the digging told me that this was the only reason they consented to Viega's punitive project in the first place. They had known where they wanted to go from the outset, they claimed. While women worked downstreamâfishing, collecting forest products, managing childrenâmen camped in the upstream forest, cleared fields on good-quality land, dug out more and more canals into the forest for themselves and their neighbors, and created the storied expeditionary spaces I am describing.

17

The landscape within which these activities took place was radically transformed. The narrow mouth of the river now gapes open more than a half mile across where it meets the Amazon, capsizing motorboats on a windy day. The swampy pirizalâunmistakably a lake nowâis a sweeping expanse of water itself nearly a mile wide. The closed upstream forest is threaded with a dense tracery of creeks, streams, and broad channels.

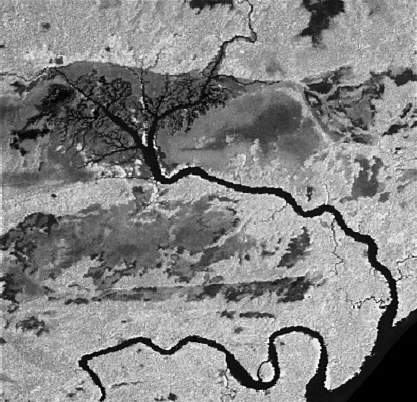

Take a look at the images on pages 60 and 61. The first is the infrared aerial photograph made by CPRM that starts this book. It was taken as part of a mineral survey of the eastern Amazon at a moment when the region was in the grip of unrestrained speculative development. This was late summer 1976, well after work had first begun in Guariba, and it shows the Rio Guariba with the Rio Preto below, and just a glimpse of the mass of the Amazon flowing by.

CPRM first mapped this part of the region in the late 1950s, but for some reason their splendid archives in Rio de Janeiro presented only a gap where I had hoped to find the Igarapé Guariba of that time, with its four families at the river-mouth, its waterfall, its obdurate pirizal, and what must have been the skinnier, shorter stream then flowing through the forest. The image on page 60 is from 1976 and is therefore the first, a commanding view of the scene some fifteen years after the digging

began. It is a classic landscape picture in the terms of Raymond Williams' famous observation that the genre is underwritten by the erasure of the labor through which nature is madeânot to mention the effacement of landscape's own work of nature-making.

18

Actually, this image goes even further, offering a land without social relations or history, a land of potentiality. In this sense, its abstraction makes it a classic Amazonian landscape, one in which the implied view is both entrepreneurial and extractive.

Yet even here, it is the broader blackness of the Rio Preto that draws the eye. The Rio Guariba is quite narrow, and the upstream area where it fragments into smaller channels is tentative and anemic. But look at this next image, taken in 1991, another fifteen years on, a Landsat TM composite satellite image to the same scale.

Same scale, same time of year, same point in the tidal cycle.

19

But when tied to its predecessor, this image creates a disruptive juxtaposition,

proposing a radical shift in narrative. Not only is the expansion of the river quite clearly apparent, but it has come alive, no anemia here. Instead, its channels proliferate, enveloping the forest like capillaries of the alveoli, at once engulfing and absorbing the terra anfÃbia of which it is a part.

There is a simple point here. Places and what passes for nature have a consuming materiality. And so do place-making and nature-making, makings that make no sense without attention to practice. So, again, how did this place come into existence?

In the midst of attention to discursive practice, we have to resist eliding the materiality of those concrete transformations that people actively undertake and remember to pay attention to fathoming events at the juncture of ideas and practices. Discourses of place and nature in Igarapé Guariba are grounded, literally. People here actually did these

things: place, nature, and locality were transformedâremade, invented evenâthrough physical, corporeal action.

Yet, in recovering practice, we need to recognize that despite its brute tactility, the digging of channels was not narrowly material. It rested on old understandings of what nature is, and it created new ones. It drew energy from political-economic and cultural projects that tied Igarapé Guariba into temporarily coherent transnational commodity circuitsâthe timber trade of the 1970s, for exampleâand it reinvigorated embedded networks of short-distance trade, such as those in palm-fruits and other forest products. The cutting of channels relied on a shared story of a nature in Igarapé Guariba that began impossibly wild but could be made to surrender its abundance. And, in enabling a present that relies for legitimation on constructions of the past and projections of the future, a discursively and physically plastic local nature became subject to co-optation and incorporation into the mobile practices of contemporary politics.

T

HE

C

ABOCLO

During the course of twenty-five careful years, Benedito and Nazaré Macedo and their family succeeded in displacing the Viegas, strategizing to exploit the spaces implicit in their personalist regime, discovering pathways between subjection and subversion.

That densely ramified upstream area in the Landsat image is where we're headed now. It was this partâknown as

o centro

20

âthat was to become the focus of the engineering activity I am describing. This is what it looks like at low tide today. The two tall stakes to the left are fishing markers, barely visible when the river rises. Behind us and in the far distance is forest. We're looking out from Tomé's retreat, a location of some significance in the unfolding of this story.

Who knows why Old Man Viega really wanted to cut these streams? There seems no doubt he was aiming to tie this rich landscape to Macapá and Belém, via both the downstream Igarapé Guariba community and the Rio Preto. Nestor Viega says that all this activity was driven by his father's need to get buffalo to the slaughterhouses in Macapá in good condition. Raimundo's widow and daughter are less instrumental: it was his “curiosity to see what was there” that drove him on, they insist.

21

It was to get bananas to Macapá, says his grandson Miguelinho.

Old Dona Terezinha, gripping my arm, by herself now that her husband has run off again, standing there in rags by the hand-dug igarapé that links the centro with the Rio Preto, remembers something else: he did it to carry his family in style by motorboat from the sawmill to the road they were building from Macapá that passed by the Rio Preto. No, states Benedito Macedo matter-of-factly, he did it to get the timber.

Viega knew the commercial potential of this good-quality land for bananas, corn, watermelon, and the marrow-like

maxixe

, and he understood the value of the forest resources that visiting hunters had reported. His fregueses were similarly informed and participated in the same project, recognizing the same potential. Yet, many of them denied the legitimacy of his claims to governance, and they used these upstream lands to generate the income that enabled them to free themselves of the burden of debt and as a basis for their subsequent land claim that pushed the patrão off the river.

Viega should have been prepared. José Macedo, Seu Benedito's son, had accumulated formidable expertise in years as a traveling representative of the

Comunidades de Base

, the Catholic base communities that preceded the rural workers' unions in Amapá.

22

And he was not alone. Igarapé Guariba had produced a generation of sophisticated political operators, including Martinho the Goat, the union leader, who had

learned the mechanics of the Viegas' operation from the insideâas the teenage clerk in the store and receiver at the warehouseâbefore studying populist Marxism and refashioning himself as feudal landlordism's relentless nemesis.

The Macedos dug channels. While Viega mapped out a route for the Rio Preto, they headed for the centro, pushing their way toward the shiny crops they envisioned growing in the mata virgem.

There was no inherent conflict in these coinciding projects. One hand was still washing the other, and, for a while at least, both were washing the same face. Better land effectively meant higher rents, as more produce entered the warehouse and more goods left the store. But the Macedos knew something Viega did not know they knew, and may perhaps not even have known himself. Through their political contacts in Macapá, José Macedo and Martinho the Goat had accessed the landlord's files in the Macapá offices of the Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA), the federal land reform agency, investigated his holdings, and confirmed their suspicion that he was exaggerating his claim. The

tÃtulo definitivo

, the outright title he had bought in the deal that gave him the Rio Preto and Igarapé Guariba, extended only 2,200 yards from the confluence of the Rio Guariba and the Amazon, nowhere near the land upstream toward which the canal-diggers were steadily heading. What was more, in an affirmation of the concrete significance of abstract argument about invisibility and anthropogenesis, this upstream land had the legal status of unoccupied land, open to petition from the state as

terra requerida

, that is, petitioned or petitionable land.

23