In Amazonia (20 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

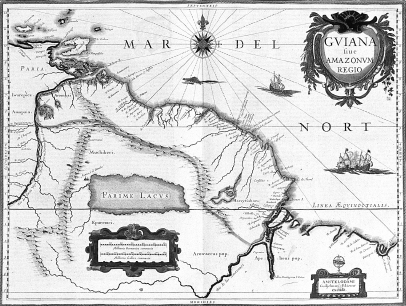

For all intents and purposes, this was also the end of Guiana. Its

imperial rationale displaced, we can trace its gradual disappearance from European cartography and incorporation within an expansive, if variable, Amazonian regionalism. Although the boundaries seem secure and the dark blob of Ralegh's Manoa still fills the central space, the inscription on the cartouche of Blaeu's map of 1638 reads “The Region of

GUIANA

or Amazon,” an index of ambivalent and shifting territory.

141

This is the beginning of a long retreat as Guiana falls back behind the borders of the northerly nation-states, leaving only a vestigial persistence as an arcane usage in scholarly ethnohistory.

142

When the English finally return to northern South America 200 years later, it is again in the idiom of discovery, following Ralegh's gloried footsteps yet beginning anew, with histories rewritten and landscapes pristine, arriving once more to claim the riches of a virgin land.

5

THE USES OF BUTTERFLIES

Bates of the Amazons, 1848â1859

A Hydrographic RegionâThe Cabanagem, Another RegionâMultiple Taxonomies and Taxonomic Immanenceâ“Where Are the Horrors?”âThe Mimesis for Which He Is FamousâUnglamorous Beginnings but a Presumptuous AgendaâDestabilizing Scientific HierarchyâPopular ScienceâA Programmatic LandscapeâRace, Nature, and DifferenceâLiberty, Independence, and YearningâCenters of Calculation, Cycles of AccumulationâThe Collection as Region-MakerâThe Power of NumbersâOverdeterminations of Spatial PracticeâMimesis and Epistemological HybriditiesâThose Pervasive Instabilities

In 1863, when Henry Walter Bates published the now famous account of his eleven years in northern South America, there was still no obvious way of naming the spaces from which he had recently returned. Bates opted to call his book

The Naturalist on the River Amazons

, revealing just how much the great river had captured contemporary imaginations.

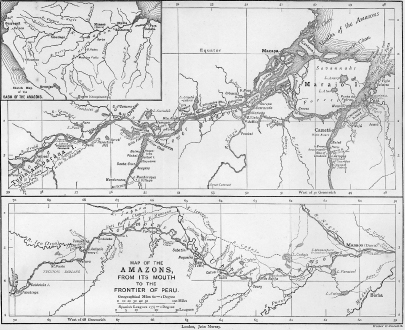

By tying himself so firmly to the river, Bates laid claim to its most alluring quality: the capacity to transgress and remake not only space, but the boundaries of geography, biology, culture, and politics. As the maps he commissioned to accompany his narrative made clear, in doing so he was swept away in the currents of an irresistible hydrography.

When Bates first crossed the Atlantic in 1848 on the barque

Mischief

, the Amazon was still largely unmapped beyond the estuary and only spottily occupied by non-Indians.

1

For the second time, European explorers found themselvesâin Humboldt's phraseâon “the New Continent,” a world reborn by the collapse of Iberian influence in the Americas and the coincident re-visioning of matter through the optic of the natural sciences.

2

By no means, though, was this unimagined territory. The northeastern reaches of what Bates sketched as “the Basin of

the Amazons” were emerging as a semi-autarkic economy with particularly close ties to Europe, and, as we know, they had long been present in metropolitan consciousness as the ambiguous location of rich and seductive resources, of a super-abundant nature, and of potential settlement. They had also, since Brazilian independence in 1822, fostered an intensifying political regionalism that in 1835 spilled over into revolt, rapidly setting fires raging throughout the countryside as a chaotic and fluctuating alliance of Indians and slaves plunged the huge province of Grão-Pará into the vortex of the Cabanagem rebellion. This latter, though, was not the region-making in which Henry Bates participated.

3

More than many contemporary travelers, Bates acknowledged the continuing shock of the Cabanagem, and its after-tremors regularly agitate his narrative. Yet, the region in which he saw himself traveling and that he brought back with him to Europe was only tangentially formed from these histories. Instead, Bates' Amazons was nourished in a matrix of his own moral and philosophical formation, the institutional and epistemological tensions of Victorian natural science, and the everyday practices of natural historical fieldwork.

Nineteenth-century naturalists traveled through a world of emergent taxonomies, a world in which nature's superficial disorder merely masked its immanent logic. New ways of figuring the distinctions between humans and nature that had developed in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and had been powerfully expressed in Linnaeus'

Systema naturae

(1753), had underwritten innovation in the physical and chemical sciences, agriculture, navigation, and allopathic medicine to make the alien and unsettling nature that had so troubled Ralegh increasingly pliant and predictable.

4

Bates set out on his adventure from a Europe flush with new habits of thought. Innovative classificatory schema were sweeping up race as well as the non-human biologies of botany and zoology and were simultaneously plotting new global geographies through the hierarchical taxa of spatial scale.

5

Despite being a process that relied on and, in fact, created particularity and difference, Victorian region-making emerged from the contradictions of a self-consciously universalizing and domesticating metropolitan science. It is in the context of these transformations that we can understand Bates' disappointment on arrival in Brazil. “Where are the dangers and horrors of the tropics?” he wrote home to his friend Edwin Brown. “I find none of them.”

6

M

IMESIS AND

A

LTERITIES

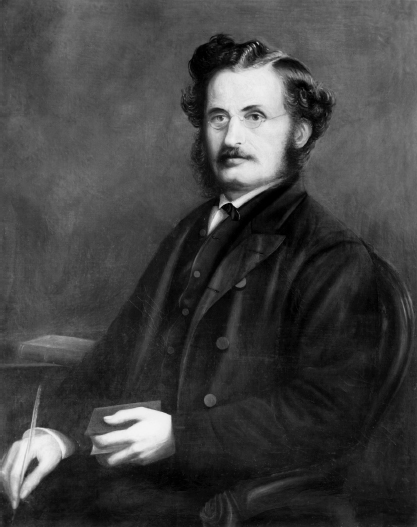

It was Amazonian butterflies and beetles that turned Henry Bates into the leading entomologist of his day and created a man who, along with his friend and temporary traveling companion Alfred Russel Wallace, still dominates the story of European entanglement in the region. Bates spent the eleven years from 1848 to 1859 in the forests, towns, and savannas of northern South America, frequently working in places no European scientist had previously set foot, assembling and cataloguing a vast natural history collection that was dominated by insect and bird specimens, but that also promised other treasuresâhuman hair, for one thingâwith a more ethnological appeal. On his return to England, he wrote

The Naturalist

, an account widely considered the pre-eminent Victorian narrative of Amazonian natural history, and he secured the coveted position of assistant secretary at the recently formed Royal Geographical Society (RGS), a post he held for the remainder of his life. This final, metropolitan phase of Bates' career placed him squarely at the institutional center of British imperial science (as well as of nascent academic geography) and makes explicit some of the connections between imperial policy and biological fieldwork that are often submerged in the celebratory narratives of Amazon exploration.

7

Back from the Amazons, c. 1859

Bates is well known to modern biologists as the discoverer of

“Batesian mimicry.” He was collecting at Ãbidos, not far from Santarém on the middle Amazon when he noticed that unusual and vulnerable butterflies were often effectively identical to common, unpalatable species and varieties that predators avoided. In Bates' view, expressed in a famous paper given at the Linnaean Society in November 1861, the protective mechanism leading to mimetic resemblance provided “a most beautiful proof of the truth of the theory of natural selection,” and Darwin enthusiastically seized upon this solution to a delicate puzzle for the definitive sixth edition of the

Origin of Species

(1872).

8

Darwin, Bates, Wallace, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and T. H. Huxley were prominent members of an assertive alliance that was to succeed in establishing the unsettling hegemony of evolutionism in the natural sciences. And there is much to be learned about the workings of British science at this formative moment from tracing the letters and specimens passing between these and other scholars as they falteringly assemble the elements of a convincing theory of natural selection and strategize on the most effective means for its deployment.

Bates was an unlikely figure to be keeping such elevated company.

9

Rising from unglamorous beginnings as a provincial amateur naturalist, he trained himself in the rudiments of scientific methodology by stealing time from apprenticeship in a hosiery warehouse. He worked the long but standard hours of artisans and the lower middle classâarriving to sweep out at 7:00

A.M.

and finishing at 8:00 in the evening, six days a weekâand he read and studied voraciously, closely following ideas current in the social theory, politics, and natural history of the day.

10

With Wallace, he debated Malthus'

Essay on the Principle of Population

(1798), Lyell's

Principles of Geology

(1830â33) and its appended summary of Lamarck's theory of the transmutation of species, Robert Chambers'

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

(1844), Humboldt's

Personal Narrative

(1816â34), Darwin's

Voyage of the âBeagle'

(1839), and, eventuallyâand decisivelyâWilliam H. Edwards'

A Voyage Up the River Amazon, Including a Residence at Pará

(1847).

11

By the time they left Liverpool in April 1848, ambitious and energized and bound for Pará, the two young naturalists had definite ideas about the possibilities of tropical adventure: their journey would solve the mystery of the origin of species.

Science was a recognized avenue of social mobility at a moment of unprecedented upheaval in industrializing British society.

12

Nonetheless, for men in their early 20s with little formal education, few connections,

and no money to speak of, this was a presumptuous agenda. The established scientific hierarchies sanctioned a clear and subordinate role for the self-educated enthusiast, the amateur lacking the cultural capital to penetrate the elite institutions then proliferating professional procedure. Needless to say, there was little encouragement to theory-making. Field-naturalists like Bates and Wallace were infantrymen in the taxonomic war on natural disorder, their spoils supplying armchair savants with the exotic specimens that crowded the natural history cabinet. And, as we might expect, the achievement in crossing class lines was to be recurrently complicated by compromise. Once Bates took up his post at the RGS, his original writing was largely restricted to narrowly focused (although massive) exercises in insect classification. The remainder of his scholarly work was editing. He compiled a richly illustrated six-volume compendium of travel and natural history vignettes, managed the Society's two journals, made newly available a number of classics of Victorian geography, and oversaw the publication of other people's exploration narratives.

13

Writing Bates' obituary in

Nature

, Wallace complained that onerous administrative duties had impeded his friend's ability to contribute to natural history and had destroyed an already frail constitution.

14

Despite lacking formal qualifications, Bates was a graduate of the rich tradition of popular education flourishing in early-nineteenth-century Britain. Although he left school at age 13 to enter apprenticeship, he managed to assemble the basis of a natural historian's education by attending night classes at the Leicester branch of the Mechanics' Institutes. Bodies such as these formed the most visible expression of a vigorous culture of radical self-improvement among English artisans during the first half of the nineteenth century, a period in which, in E. P. Thompson's words, “the towns, and even the villages, hummed with the energy of the autodidact.”

15