In Arabian Nights (28 page)

Authors: Tahir Shah

When Sukayna visited us and told me that the stairs and the

high ceiling were symbols, I understood exactly what she meant,

because I remembered sitting on the lawn with my box of bricks.

The astrologer's idea, the symbols of Heaven and Hell, sounded

preposterous.

But the more I turned it in my mind, the more sense it made.

In Morocco, and in the Arab world, symbols are all around,

just as they are everywhere else. But the difference is that the Oriental

mind can make sense of them, decipher them. People are trained to recognize

symbols, to understand through a chain of transmission that stretches back

centuries. The Occidental world once had the same chain but, somewhere along

the line, one of the links was broken and the chain collapsed. The result

is that the symbols that ornament Western society – and are quite plain

to Orientals – can't be decoded any longer by the Western mind. They

are regarded as nothing more than pretty decoration or, in the case of stories,

as simple entertainment.

A few days after Noureddine went into hospital, I heard from

Osman that a date had been given for the demolition of the

bidonville

. It was to take place the next month, a week after

the move to newly-built tower blocks up the hill in Hay Hassani.

The guardians and Zohra, who all lived in the shantytown, were

unable to contain their excitement.

'We are going to have hot water in the bathroom,' said

Osman, 'and special windows that do not let in the cold.'

'And there will be a lift that zooms up to the top,' said the

Bear.

'And from there, we shall have a view of the whole of

Morocco,' Zohra added.

'What will happen to the land on which the

bidonville

is

built?' I asked.

Marwan swept his hand out sideways.

'Flattened,' he said. 'Then there will be buildings, lots of them.'

'What kind of buildings?'

'Villas for the rich,' said Osman.

'People with a lot of money.'

'Casa Trash,' I said.

The fact that the Caliph's House is located where it is – slap

bang in the middle of the city's prime shantytown – gives us a

window into a world where people are less financially fortunate.

As time has passed, we have developed an abiding respect for

everyone who lives in the

bidonville

. The people who live there

may not have pockets lined with money, but their heads are

screwed on right. Their values are rock solid.

If the shantytown is at one end of the equation, then Casa

Trash can be found far at the other extreme. Their lives are

created from an alphabet of name brands, cosmetic surgery and

monstrous black SUVs. Female Casa Trash is dressed in the

latest Gucci or Chanel, is heeled in Prada and is so thin that you

wonder how her organs function at all. Her vision is obscured by

oversized sun goggles and her mouth is masked in lipstick of

such thickness and viscosity that it hinders her speech.

She can be found in a handful of chichi haunts, such as Chez

Paul, picking at platters of imported salad leaves, smoking

designer cigarettes and rearranging her curls. She never looks at

the friend she has come to lunch with, because she is on her

phone and too preoccupied scanning the other tables, making

sure she's been seen.

The male variety of Casa Trash carries at least two mobile

phones and has a diamond-encrusted Rolex on his wrist. He

drives a black German 4x4 with frosted windows and aromatic

rawhide seats. He wears a black leather jacket, tight Levi 501s

and so much aftershave that your eyes water as he passes. To

show just how important he is, he speaks in little more than a

whisper. His hair, weighed down with handfuls of gel, shines

like a bowling ball and his teeth have been chemically whitened

to create a Hollywood smile.

Casa Trash almost never come to the Caliph's House, partly

because they are not normally invited, but also because, for them,

the idea of fording a full-on shantytown is tantamount to committing

bourgeois suicide. When they do come, we find them at

the door, the women shaking in their high heels, the men

inspecting the chassis of their car for damage.

On one occasion in the first week of March, a Casa Trash

couple did penetrate our defences. They had seen an article

about me in

Time

and had known a previous owner of Dar

Khalifa. They drove at high speed through the

bidonville

, schoolchildren

scattering in the nick of time before the black Porsche

Cayenne crushed them into dust. The husband whispered he

was an industrialist. He lit a cigar as thick as his wrist and asked

me if the area was safe. Just before I answered, he pulled out a

pair of mobile phones and whispered into them both at once.

His trophy wife seemed to have spent much of her adult years

on a surgeon's table. The skin on her face was so tight and so

loaded with Botox, I feared it might split right then. Her lips had

been cosmetically edged with a dark pink line, her teeth capped,

and it looked as if a pair of tennis balls had been pushed down

her blouse.

The guardians were whitewashing the front of the house

when the Casa Trash couple arrived. On the way into the house,

the husband slipped his car key to Marwan and barked an order

fast in Arabic to wash the vehicle down. I led the couple into the

house for a show of forced hospitality. As we moved through

the hallway, the Casa Trash wife waved a hand back towards the

shantytown.

'Those poor little people,' she said, 'living in those squalid little

shacks. It's a shame on our society.'

'But the homes in the

bidonville

are spotlessly clean inside,' I

replied defensively. 'Everyone who lives there is well dressed and

clean as well. Despite the lack of running water.'

The wife twisted a solitaire diamond on her finger.

'You must remember that they're not true Moroccans,' she

said.

'I don't understand you,' I said, my hackles rising.

'They're thieves,' whispered the Casa Trash husband between

phone calls. 'Nothing but thieves.'

Thankfully the couple left almost as soon as they had arrived.

When they were gone, I went outside. The guardians were

gloomy because the stork had disappeared again. As I was standing

there outside the house, a little girl approached down the

lane from the

bidonville

. She couldn't have been more than about

seven. Her cheeks were rosy, her hair tied back in a ponytail. In

her hand was a posy. They were not the kind of flowers you find

in the fancy French florists in Maarif, but were in a way all the

more beautiful. The little girl approached me, half nervous and

half proud. When she was about two feet away, she motioned for

me to bend down. I did so. She kissed my cheek, placed the posy

on my hand and said, '

Shukran

.'

I didn't understand why she had thanked me. I asked

Marwan, who was standing there.

'She was thanking you, Monsieur Tahir,' he said, 'for not looking

upon us with shame.'

The next afternoon, I dropped in on the hospital where the

cobbler was convalescing. I made my way through the dim

corridors, which echoed with the sound of bedpans and patients

moaning, and traced the route back to his ward. He was lying

asleep in a bed beside the door, his face grey rather than its

characteristic dark brown. He was struggling to fill his lungs.

An oxygen mask had been fitted to aid his strained breathing

and a drip was feeding his arm.

I stood there for quite a while just looking at him.

The man in the next bed had his legs strapped and his head

was bandaged tight. He seemed delirious, but his eyes managed

to follow me as I crossed the room to take a chair over to the

cobbler's bed. I leaned forward and held the old man's hand. It

was cold and the fingers were almost purple. As I sat there, clearing

my mind of the insignificant debris that tends to fill it, I

remembered visiting one of Rachana's relatives in an Indian

hospital some years before. The lady was in intensive care. We

were permitted to go in a few minutes at a time. At the far end

of the sterile room were ranged three small incubation units.

Inside them were triplets, a day old – two girls and a boy. The

father was there, his face ashen, dejected. The nurse said the little

girls were expected to live, but the boy was so frail his chances

were slim.

I visited two or three days in a row to see Rachana's relative.

Every time I dropped by, I heard the babies' father talking to the

boy in a whisper. He paid hardly any attention to the girls, spoke

only to his son. By the end of the week the little girls were both

dead. Their brother, although feeble, was expected to survive.

All the while, his father continued talking to the boy. He didn't

stop for a moment.

I asked one of the nurses what he was saying.

She said, 'He's telling him the epic tale of the

Mahabarata

.'

'But the child isn't awake.'

'It doesn't matter,' she replied. 'The words slip into the

subconscious.'

Sitting at Noureddine's bedside and remembering the experience

in India, I pushed a little closer to the bed. Holding his hand, I recounted

a tale my father had told me as a child, when I was lying sick in my bed –

the story of 'The Man Who Turned into a Mule'.

The night after visiting the cobbler, I dreamed of the magic carpet

again. Weeks had passed since I had last been wafted up into

the night sky, carried away to its distant kingdom. As soon as I

saw the carpet lying there, laid out on the lawn, I ran to it,

stepped aboard and sensed its fibres bristle with eagerness to get

away. With the breeze rustling through the eucalyptus trees, we

left the Caliph's House far behind and travelled out over the

Atlantic, what the Arabs call

Bahr Adulumat

, the Sea of

Darkness.

The carpet flew faster than before, pushing up higher and

higher to where the air was thin. The stars above were bright

like lanterns and, as we flew at great speed, I glimpsed the curve

of the earth's atmosphere. Suddenly, we plunged. Spiralling

down, my cheeks pinned back, like a skydiver in freefall. At first

I screamed, but there was no one to hear me. No one except for

the carpet. I clung on to its edge, spread-eagled, but I became too

hoarse to shout. Then, gradually, our rate of descent reduced and

we were flying horizontal once again.

The carpet skimmed over a thousand domed roofs, over

streets and across grassland. I sat up and then a very strange

thing happened. I found I could understand what the carpet was

saying.

'Everything I show you has a meaning,' it said. 'Sometimes we

know at once what something represents. But at other times we

have to turn the signs around in our heads and decipher them.

Do you understand me?'

'Is that you, the carpet, talking to me?'

'You know it's me,' said the carpet, bristling, 'and you heard

what I asked.'

'I understand,' I said. 'But I don't really know what's going

on.'

The carpet banked right and soared down a black street lined

with windows, each one shrouded in gauze. In every window

was a candle. It made for a chilling sight.

'What is this place?' I asked.

'You know it,' said the carpet.

'No, I don't.'

'Yes . . . remember my words, that what I show you has a

meaning.'

'Well, what could this mean?'

'Think! Think!'

'I don't know!'

'Yes, you do, but you must let your imagination tell you.'

'I closed my eyes as we flew, faster and faster down the pitch-black

street, each house a facsimile of the last – six windows with

a solemn candle in each, the flames flickering as we passed.

'The street is Death,' I said, 'and the windows are Hope.'

'And the candles that burn in them?'

'They are . . .'

'Yes?' the carpet yelled. 'What are they?'

'They are Innocence.'

The next morning, I sat up in bed, my eyes circled with fear.

All I could think of was the princess at the gallows. What did she

represent? I thought hard, imagined all kinds of lunacy. Then it

hit me. It was obvious, right in my face.

The girl standing at the gallows was my own ambition.

'The king spoke to me this morning!' exclaimed Joha at

the teahouse.

'What did he say?'

'Get out of my way, you idiot!'

I RETURNED TO THE HOSPITAL A DAY LATER TO FIND THE

cobbler's bed stripped of its sheets and the nightstand cleared.

My stomach felt sick with bile. The man at the next bed was still

there, his legs suspended with wires and weights.

I stopped a nurse and motioned to the empty bed.

'Mr Noureddine,' I said, 'has he been moved?'

'He was very old.'

'I know. But where is he? In another room?'

She looked at me, her eyes reading my dread.

'He is in Paradise,' she said.

I was too sad to stay in Casablanca a moment longer. I told

Rachana to pack some clothes, and Ariane and Timur to fetch

their favourite toys.

'We are going away,' I said.

'Where?'

'I'm not sure.'

'How long are we going for?'

'A couple of days, a week, a month.'

A short time later we were all in the car sitting in the lane. The

cases had been piled in the back and the seat belts fastened.

The children were already fighting. I had left money with

Osman to pay the guardians for four weeks and had given him a

note for Dr Mehdi, to be taken to Café Mabrook the following

Friday afternoon. It said simply:

Gone to search for my story

.

We drove down the lane and through the

bidonville

. The fishseller

had rolled his cart down the track from the road. It was

surrounded by a cacophony of cats. The knife sharpener was

there, too, and the man who wrote letters for the illiterate, and

two dozen children playing marbles in the mud.

Rachana asked again where we were heading. I didn't answer,

but thought back to the security of my childhood. I was squeezed

up in our red Ford Cortina, between my twin sister, Safia, and a

giant brass candlestick my mother had got cheap in Marrakech.

The car was low to the ground, whining, weighed down with

mountains of bargains. My father was haranguing the gardener

on the taste of Kabuli melons in Afghanistan and my mother

was knitting a fluorescent pink shawl. My older sister, Saira, was

on the back seat, her head pushed out of the open window, about

to be sick. The car was freewheeling downhill across farmland,

the soil nut-brown and moist. There was a screen of tall trees,

their leaves quivering in the breeze that precedes the rain. After

it was a signpost. My Arabic was almost nonexistent, but Slipper

Feet had ground its alphabet into my head. I read the sign: 'Fès.'

The word caught my father's eye too.

'Fès!' he cried out halfway through a sentence about Afghan

pilau. 'It's the dark heart of Morocco. It is the

Arabian Nights

.'

For a third time Rachana asked the name of our destination.

I had a flash of the storytellers crouching outside the great city

walls, then another of the tanneries, which look like something

out of the Old Testament.

'Baba, where are we going?' asked Ariane.

'We are going to the dark heart of Morocco,' I said.

After three hours on the highway, we descended across the same

nut-brown fields I had seen as a child. The sky boiled with anvil

clouds, the earth below it lush from months of rain. Ariane

spotted a large stone in the middle of the highway, then another

and another. They were all the same shape – smooth and oval,

about the size of a tortoise . . . Then I realized: they

were

tortoises

and were about to be flattened by the giant red truck we had

struggled to overtake a mile before.

With Ariane in tears at the thought of the execution of her

favourite animals, I did an emergency stop, threw the car into

reverse and leapt out. The truck was close and closing in, freewheeling

down on to the nut-brown plain, the driver's crazed

face already visible in the cabin. I jumped into the fast lane,

scooped up the first tortoise and, in the same movement, another

three. The truck was now so close that I could see deep into the

driver's bloodshot eyes. They told a tale of a life dependent on

kif

.

My arms juggling tortoises, I spun to the side and managed to

lay the little reptiles in the soft grass at the edge of the highway.

Ariane had calmed down on the back seat. She said that a witch

had once turned a handsome prince into a tortoise for laughing

at her warts.

'Who told you that, Ariane?'

She thought for a moment.

'The Queen of the Fairies did,' she said.

There can be no place in the Arab world quite as bewitching as

Fès.

We reached the ancient city as twilight melded into night.

There were no stars and no more than the thinnest splinter of a

moon. A blanket of darkness shrouded the buildings, muffling

the last words of the evening call to the faithful. Arriving at Fès

by night is almost impossible to describe accurately. There's a

sense that you're intruding upon something so secretive and so

grave that you will be changed by the experience.

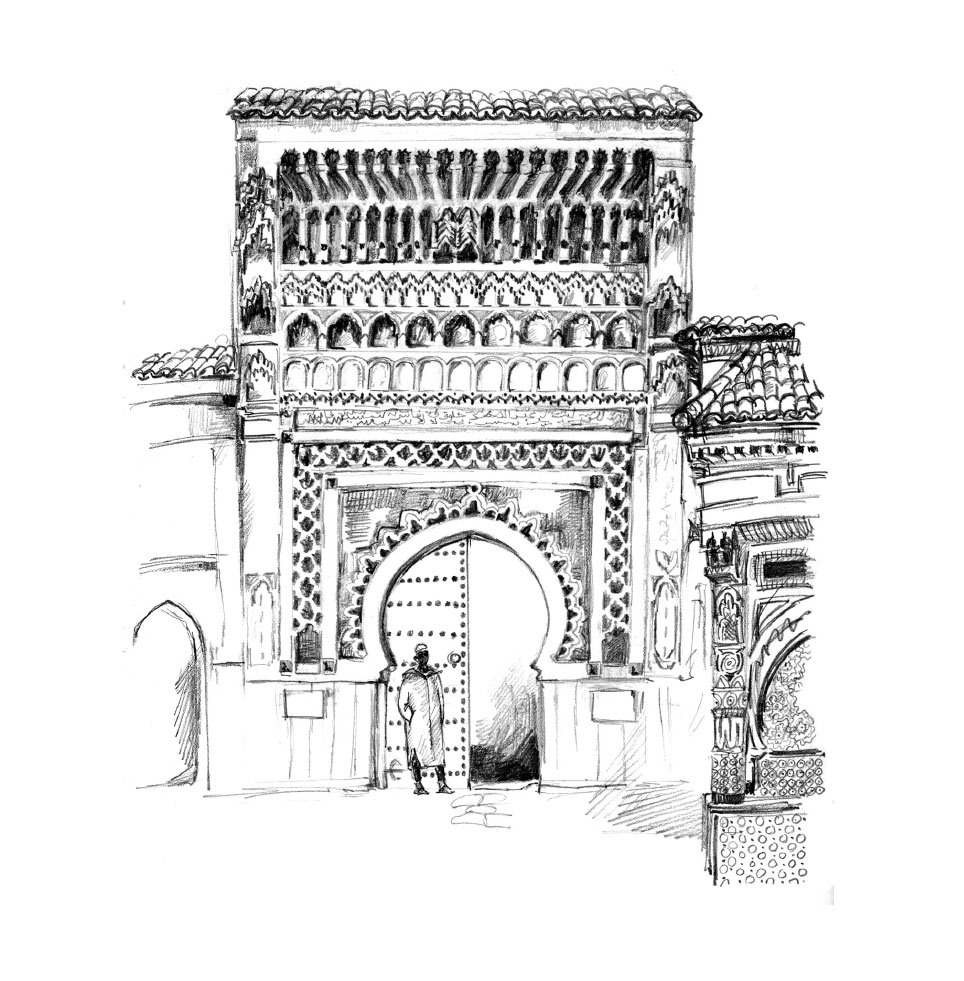

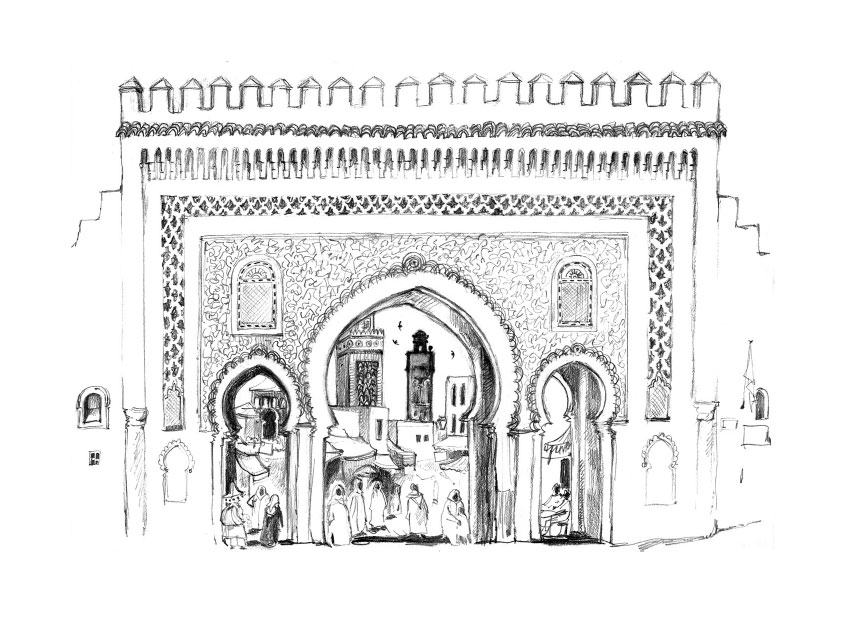

We found a small guest-house deep in the medina through

Bab Er-Rsif, one of the central gates. I hauled the cases there and

shepherded Rachana and the children through the labyrinth, to

the door. The owner offered two rooms for the price of one. He

said it was because we had brought

baraka

into his home – in the

shape of children.

'A house without children is like a landscape without trees,'

he said. 'It may be beautiful, but there is emptiness.'

He bent down, kissed Ariane and Timur on the head and

then on each cheek. I found myself thinking about it later. If we

were in the West and a man you didn't know covered your

children in kisses, his motives might be considered questionable.

In Morocco, however, a gentle innocence still prevails, as it did in

the Western world until a generation ago.

Just before we turned in for bed, the owner rapped at our door.

I half wondered if he wanted to kiss the children goodnight. But

he had come to say that a man was waiting for me downstairs.

'Who is he?'

'A foreigner.'

I went down. A single forty-watt bulb struggled to illuminate

the hallway, projecting long shadows over the walls. The man

was standing near the door, wearing what looked like a Stetson.

He was smoking a cheroot.

'It's Robert,' he said.

'Robert?'

'Robert Twigger.'

I shook his hand.

'My God, it's been years. How did you find me?'

'The medina grapevine,' he said.

At dawn I crawled out of bed, woken by the muezzin, and made

my way to the vantage point above the old city, at the Merinid

Tombs. The first blush of pink light had touched the medina,

where the only sign of life was the smoke rising solemnly from

the bakeries in the twisting maze below. My father had taken me

to the same spot thirty years before. He said that watching Fès

was like peering into a world that had disappeared centuries ago.

'This is the city of Sindbad, Aladdin and Ali Baba,' he said, 'of

jinns and ghouls and the medieval Arab world.'

'But the

Arabian Nights

were set in Baghdad, Baba.'

'That's right, but Fès now is how Baghdad was then.'

'It's dangerous,' I said.

'Tahir Jan, what you think of as danger is the soul. Stretch out

to touch it. Embrace it.'

We had stood at the Merinid Tombs each morning for a week.

On the last day, my father touched my shoulder as we walked

back to the red Ford.

'Fès will be important in your life,' he said.

'How do you know?'

'Because it's a centre of learning, a place where transmission

takes place.'

'But, Baba, it's just an old city,' I said.

My father's face froze.

'Never do that,' he said coldly.

'Do what?'

'Never call a diamond a piece of glass.'

He opened the car door for me and stared into my eyes so

forcefully that I found it hard to breathe.

'Fès is where the baton is passed on,' he said.

The first time I met Robert Twigger was fifteen years ago when

I was homeless in Japan. He was a poet with a fondness for

martial arts, a friend of a friend. I had travelled to Tokyo to

study the culture and language of the indigenous Ainu people,

the original inhabitants of the Japanese islands. Unfortunately I

had severely misgauged the cost of living. Tokyo at the time was

the most expensive city on earth. A cup of coffee, albeit flaked

with gold leaf, could set you back a week's wages.

Ten days after arriving, I had blown my entire savings, most

of them on a single elaborate meal of Kobe beef, from a herd so

pampered that each cow boasted its own private masseur. When

Twigger found me, I was squatting in a disused office block,

living on ornamental cabbages I had stolen from Ueno Park,

where they grew in the flower beds. I would cook three at a time

and stir in a couple of heaped spoons of monosodium glutamate.

It wasn't what most people regard as luxury. But then real

luxury is in the eye of the beholder.

Twigger took me in. While I lived on his floor, simmering my

infamous soup for us both, he would spend all his time preparing

for the harshest martial arts course in the world. It was a

form of aikido, a course designed to harden the Tokyo Riot

Police. During the months I lodged with him, Twigger would

spend the evenings talking of a dream that had gripped him

since infancy – to find a lost race of cave-dwelling dwarfs

thought to reside in Morocco's Atlas mountains.

For a decade, he subjected himself to routines of wild preparation.

He took to sleeping on a bed of nails that he had made

himself, learned to shoot a pistol blindfolded and even canoed

across Canada upstream to build the muscles on his arms.

From the beginning, he was certain the dwarfs were part of a

pygmy race that had once inhabited all of north Africa. His

interest in the subject had arisen as a child. He had read a

curious monograph entitled

The Dwarfs of Mount Atlas

by the

nineteenth-century scholar R. G. Haliburton. The paper suggested

that the dwarf people were afforded an almost sacred status,

and that their whereabouts was kept secret from outsiders.

Twigger believed that a local community somewhere in

Morocco must have known stories of the small people. After all, he

said, the subject had been a sensation when it first reached the West

a little over a century ago. Trapped in the communal knowledge of

the society he felt sure there was a clue waiting to be unearthed, a

clue that could lead him to the lost tribe of Moroccan pygmies.

We met for coffee the next morning, at a café outside Bab Er-Rsif.

The place was filled with a dozen unshaven men in tattered

jelabas

, each one nursing a glass of

café noir

, with a cigarette stub

screwed into the corner of his mouth. Rachana had taken the

children to a

hammam

. She said male cafés were worthy only of

men who frequented them.

I couldn't understand what Twigger was doing in Fès.

'You're not going to find your lost pygmy tribe here,' I said,

once we had both been served coffee.

'I know that.'

'So what are you doing in town?'

'Looking for clues,' he said.

'In the old city?'

'Kind of . . . in cafés like this one.'

I swilled a mouthful of coffee.

'I'm not quite sure I see the connection.'

'It's in the folklore,' he said.

'Meaning?'

'Meaning you've got to tap into the substrata.'

I ordered another round of coffee. Twigger lit a cheroot and

sucked at the end.

'Anthropologists are a pathetic bunch,' he said. 'They never

find anything because they don't know how to look.'

'How do you look?'

'With my eyes closed.'

That afternoon, I had a chat with the owner of the guest-house

in which we were staying. He said his brother had committed

the entire Qur'ān and the Hadith to memory by the age of

twelve, that his ability to remember was so defined he had

created a business from it.