In Arabian Nights (24 page)

Authors: Tahir Shah

'Whenever they saw the king's cortege riding through the

streets, the people bowed down. And if anyone needed to ask a

favour they could do so and their great monarch always granted

whatever they asked.

'News of Hatim Tai's generosity spread far and wide and

reached the ears of a neighbouring king. He was called Jaleel.

One day, unable to take the stories any longer, he sent a

messenger all dressed in black to the court of Hatim Tai. The

messenger handed over a proclamation. It read: "O King Hatim

Tai, I am master of a far greater land than yours, with a stronger

army and far richer treasure store. I will descend upon your

kingdom and kill every man, woman and child, unless you

surrender immediately."

'Hatim Tai's advisers all clustered around. "We will go to war

with the evil Jaleel," said the grand vizier, "for every fighting

man would gladly lay down their life for you." King Hatim Tai

heard his vizier's words. Then he raised a hand. "Listen, my

courtiers," he said. "I am the one Jaleel has demanded. I cannot

allow my people to face such terror. So I shall allow him to take

my kingdom."

'Packing a few dates and nuts in a cloth, Hatim Tai set off to

seek shelter in the mountains as a dervish. The very next day, the

conquering warriors swept in, with Jaleel at their head.

'The new king installed himself in the palace and offered a

ransom for anyone who would bring him Hatim Tai dead or

alive. "How could you trust a king who would run away like

this," he shouted from the palace walls, "rather than stand and

fight like a man?"

'Hatim Tai wore the dress of a peasant and lived a simple

existence in the mountains, surviving on berries and wild honey.

There was no one who would ever have turned him in to Jaleel's

secret guard, for they loved him so.

'Months passed and still there was no sign of Hatim Tai. Then

one day Jaleel decided to hold a feast. At the festivities he

doubled the ransom. He stood up and scorned the memory of

Hatim Tai, declaring again that the generous king had run off

rather than face battle. No sooner had he finished than a child

stood up and shouted: "Evil King Jaleel, our good King Hatim

Tai disappeared to the mountains rather than spill a drop of our

blood." Jaleel fell into his chair. Even now he was a hermit,

Hatim Tai was showing compassion.

'Jaleel doubled the ransom for the wise king, declaring that

anyone who could capture him would be buried in gold. At the

same time, he raised taxes and forced all the young men into his

army and many of the young women into his harem.

'Hatim Tai was gathering berries in the mountains near the

cave he had made his home when he saw an old man and his

wife, gathering sticks. The old man said to his wife: "I wish

Hatim Tai was still our king, because life under Jaleel is too

hard. The tax, the price of goods in the market. It is all too much

to bear." "If only we could find Hatim Tai," said his wife, "then

we could end our days in luxury."

'At that moment, Hatim Tai jumped out before them and

pulled off his disguise. "I am your king," he said. "Take me to

Jaleel and you will be rewarded with the ransom." The old

couple fell to their knees. "Forgive my wife, great king," said the

old man. "She never meant to say such a terrible thing."

'Just then, the royal guards came upon the group and arrested

them all. They found themselves in front of Jaleel in chains.

"Who are these peasants?" he cried. "Your Highness," said the

old man, "allow me to speak. I am a woodcutter and I was in the

mountain forest with my wife. Seeing our poverty, King Hatim

Tai revealed himself to us and ordered us to turn him in, in

exchange for the ransom."

'King Hatim Tai stood as tall as his chains would allow. "It is

right," he said. "This old couple discovered me. Please reward

them with the ransom as you promised you would."

'King Jaleel could not believe the depth of Hatim Tai's generosity.

He ordered the king to be unchained. Kneeling down before him, he gave back

his throne and swore to protect him until the end of his days.'

When Fouad had finished the story, he hunched his shoulders

and stared at the fire's flames. It was almost dusk. The first star

showed itself, glinting like an all-seeing eye above. On earth

there was the call of a wild dog far away. Lying there on a

blanket, cloaked in darkness, I understood how the

Arabian

Nights

had come about. Campfire flames fuelled my imagination,

as they had done throughout history for the desert tribes.

Fouad pressed his right hand to his heart.

'I love the story of Hatim Tai very much,' he said. 'On some

nights when I am here alone, with a small fire to keep me warm,

I tell myself that story. Each time I hear it, I feel a little more at

peace.'

He took a pinch of the salt I had collected and sprinkled it on

the ground, to keep the jinns at bay.

'When I have heard it,' he said, 'I sit here and think what a

good man King Hatim Tai must have been.'

'Do you think the story's true?'

'Yes.'

'Why?'

'Because it is truth.'

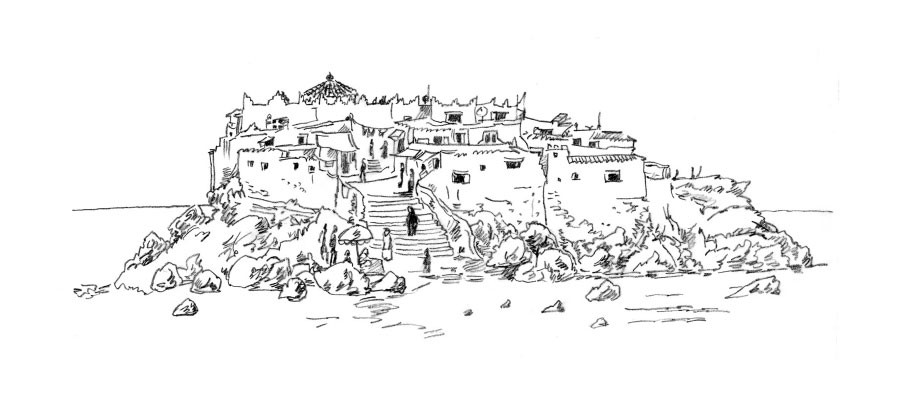

Four days after leaving the salt lake, I arrived back in the chaos

of Casablanca.

A dense winter fog tinged with pollution had engulfed the

city. The result was gridlocked traffic and a great deal of bad

feeling. At every crossing there was broken glass with at least

one pair of enraged motorists shaking their fists. As my taxi

slalomed between accidents, I felt a sense of pride. Casablanca

had not changed in the few days I had been away, but

I

had. I

had seen oceans of date palms and oases, dusty Berber villages,

and had slept under the Saharan stars.

At Dar Khalifa, the children huddled round and asked what

I'd brought them. I fished a hand into my pocket and pulled out

a thread of yellow fibre. I gave it to Ariane. She asked if it was a

strand of a princess's hair.

'Of course it is,' I said. 'And it is also an ant's rope and a piece

of fibre from a cactus growing in the greatest desert on earth.'

Timur pushed forward.

'For me?' he said.

I rooted about in my pocket a second time and pulled out

something smooth black with a streak of grey running down the

side.

It was a pebble.

'I've brought you this,' I said, kissing his cheek.

'What is it, Baba?'

'It's so many things.'

That evening I telephoned Dr Mehdi. It was Saturday and I

couldn't wait until the following Friday afternoon for our usual

rendezvous. The doctor gave me the address of his house.

'Have you got the salt?'

'Yes!'

'Please come at once,' he said.

The doctor lived in a square prewar villa on a quiet street

overlooking a row of derelict factories. He led me into the salon

and apologized for the clutter. The place was like a museum,

filled with orderly piles of books and French magazines, with

wooden boxes, papers, maps rolled up, knickknacks, mementoes

and lamps. Every inch of wall space was hung with paintings.

Some were large, broad strokes of bright abstract colour; others,

sombre and small.

'You have so much art,' I said.

'Where?'

'On the walls.'

Dr Mehdi pointed to a chair.

'I don't see it,' he said.

'How can you not see it?'

'Because it is a part of me.'

He apologized for the mess a second time, picked up a newspaper,

and let it drop on top of a dirty plate.

'My wife has gone to Fès to see her sister,' he said. 'And the

maid has run away.'

'I've brought the salt.'

'Wait a moment,' said Dr Mehdi. 'First tell me about your

journey.'

'It was wonderful. I went right down into the Sahara. I slept

in the desert. It's another world.'

'Who did you meet?'

'All sorts of people.'

'Who?'

'There was a carpet-seller and his son in Zagora, a man called

Mustapha who made good lamb stew in Ouarzazate, a healer in

Tamegroute, a man and his father in a village who gave me some

bread, an American called Fox from Iowa, and a Tuareg called

Fouad.'

Dr Mehdi washed his hands together.

'Excellent,' he said.

'Look, look, I've got the salt.'

'Wait a moment . . . tell me, what did you learn?'

'Um, er . . . all kinds of things.'

'Such as . . . ?'

'I learned about a man called Jumar Khan and his magnificent

horse, and about the generosity of Hatim Tai, and I learned

about dates in the Draa Valley, and about the desert, and . . .'

'And . . . ?'

'And I learned about solitude,' I said.

The doctor seemed pleased.

'In a week you have seen so many things, met so many

people,' he said. 'In the same time you may have stayed here in

Casablanca and seen nothing new at all.'

Dr Mehdi stood up and walked over to a bold modernist

painting of a man with three hands and a single eye offset on his

forehead.

'I don't see this any more,' he said, 'or any of the others,

because they are always here. My mind filters them out. The

only way I would see them would be if they were gone.'

He led me out into the garden. It was laid with rubbery

African grass and had miniature lights hidden in the path.

'Show me the salt,' he said.

I opened my satchel and brought out the plastic bag. Dr

Mehdi untied the knot and dug his fingers into the grey powder.

He held it to his nose, felt the consistency, nodded.

'The salt lake,' he said. 'I used to camp there as a child.'

'Is there enough salt for the wedding?'

The surgeon took a deep breath.

'There is no wedding,' he said.

'What?'

'The favour I asked you was less of a favour to me and more

of a favour to yourself.'

'I don't understand.'

'Think of the things you have seen, the people you have met

and the stories you have heard,' he said, emptying the bag of salt

on to the path. 'You are a different man than you were seven

days ago.'

Your medicine is in you, and you do not observe it.

Your ailment is from yourself, and you do not register it.

Hazrat Ali

THE DOOR-TO-DOOR DENTIST ARRIVED IN THE

BIDONVILLE

AND

set up a stall in the sun. He was fine-boned and fragile and

looked like the kind of man who, in childhood, pulled the legs

off spiders for amusement. His face was blotchy red, his

neck slim and his teeth very rotten indeed. He laid out a

moss-green cloth and placed upon it an assortment of

instruments and prosthetic devices. His tools ranged in

size and shape and were covered in varying degrees by

rust.

There were giant pairs of pliers, callipers and steel-tipped

picks, lengths of bright-orange rubber hose, spittoons,

tourniquets and clamps. Beside the impressive array was a

miniature mountain of second-hand human teeth.

I found Zohra hovering about at the stall. One of her molars

had recently fallen out, the consequence of taking six sugar

lumps in her tea. A tooth was selected from a mountain and

placed on her palm.

The dentist spat out a price.

'

B'saf!

Too much!' snapped Zohra.

Another figure was given.

The maid weighed the tooth in her hand. The dentist passed

her a mirror and she held it in place. She blushed.

'

Safi, yalla

, all right then, let's go.'

'Where's he going to fit it?'

'In my house.'

I walked down to the beach across dunes thick with marram

grass and watched the waves. We live close by the ocean, but I

don't go there very often, except to fly my kite. It seems too easy,

as if I haven't earned such a tremendous sight. That afternoon,

when I crossed the sand and strolled down to the water, I didn't

do it for myself. I did it for the young man I had met, who

dreamed of crossing the ocean, of going to America.

I ambled down the line where light sand met dark and I

thought about what Dr Mehdi had said, about the power of seeing

with fresh eyes. At first I had resented him for discarding the

salt, something I had travelled so far to fetch. But his wisdom

had gnawed away at me.

He was quite right.

The best medicine is sometimes not medicine at all.

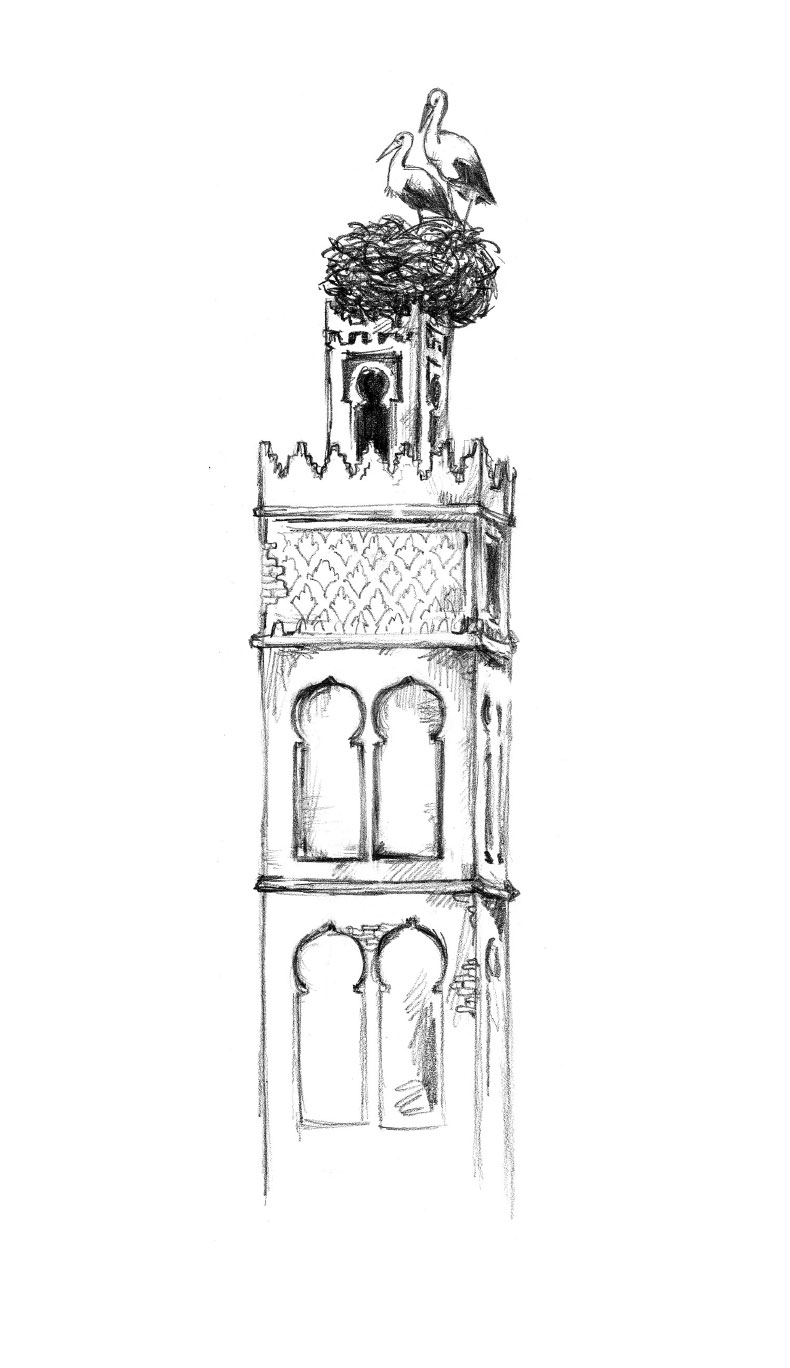

For once, there had been tranquillity in my absence. Rachana

said the guardians had been preoccupied with watching a stork

which had begun to build a nest on top of the roof. They spent

all their time straining against the bright winter light to get a

glimpse of the great white bird.

As soon as I went into the garden, they dragged me over to

their viewpoint.

'

Allahu akbar!

God is great!' Marwan shouted. 'This is a blessing

on the house, and a great thing for us all.'

'A bird's nest?'

'This is no ordinary bird,' Osman chipped in.

'It's a stork!' shouted the Bear.

'Can you believe it, a stork, here!' said Marwan.

'What's so good about a stork?' I asked. 'There are egret nests

by the dozen and you don't ever talk about those.'

The guardians gathered round and shook their heads.

'You do not know, Monsieur Tahir.'

'Don't know what?'

'Our tradition.'

Three days after getting back from the desert, I got the feeling

someone was following me. I was certain of it. The first time was

when I was buying a sack of oranges in Hay Hassani. I had paid

the money and was taking the fruit to the car, when I saw a red

baseball cap duck behind a pick-up truck. I didn't think much of

it at the time. But later that day I spotted the cap again, in

Maarif. I was going to Café Lugano to meet Abdelmalik. This

time I had turned sharply and saw it darting round a corner.

A couple of days passed. I almost forgot about the red cap.

Then I went to see Sukayna at the mattress shop in Hay Hassani.

She had given me some powder to sprinkle in the corners of the

sitting room. She said it would help the house to heal itself.

When I asked her what it was, she hadn't wanted to tell me. I

pressed her.

'It's very special salt,' she said.

'From the ocean?'

'No, from the Sahara.'

As I was leaving the mattress shop, I saw the cap ducking out

of sight again. I didn't get a look at the face, but ran after it. After

a minute or two the man lost me in the back streets of Hay

Hassani's forest of white apartment blocks. I returned to Dar

Khalifa with the salt, concerned that someone should want to

spy on me.

Zohra was holding court in the kitchen and was smiling

broadly again. The tooth was fitted and looked quite good. I

asked if the surgery had been painful. She winced.

'Worse than childbirth,' she said.

Osman came to the kitchen to inspect Zohra's dentistry. His

mouth was a dentist's casebook. He asked the maid about the

pain.

'You could never stand pain like that,' she said.

Osman straightened his back.

'Of course I could.'

'Impossible,' she replied. 'You are just a man.'

The guardian asked me if he could have an advance on his

wages. He took the money and stormed off to find the dentist.

When he was out of earshot, Zohra said, 'Moroccan men are

like cooking pumpkins.'

'How is that?'

'Quite hard on the exterior, but all pulp on the inside.'

The guardians cleared all the dead twigs from the hibiscus hedge

and laid them out on the roof for the stork. Then they filled a

washing tub with water and hauled it up there too. I quizzed

them on what they were doing.

'Storks are very lazy,' said the Bear. 'They don't like building

nests because it takes so much work.'

'But I'm sure he can handle the task.'

'It's not a he,' cracked Marwan. 'It's a female and she has come

to lay an egg.'

'How do you know?'

Marwan rubbed his eyes.

'I just know these things,' he said.

I asked why storks were such an omen of good fortune.

The Bear explained: 'There was once a judge who killed his

wife by strangling her. He buried her body and married a young

woman. As a punishment, God turned the judge into a stork.'

'Where did you hear that?'

'Everyone knows it,' said Marwan.

Confused, I went to the kitchen, where Zohra was cuddling

Timur in her arms. I asked her what she knew about storks. She

had never heard the story of the judge who murdered his wife.

'Those men spend too much time talking rubbish and not

enough time working,' she said.

An hour later, I went back into the garden and glanced up at

the roof. I did a double take. The stork had disappeared.

Marwan and the Bear were weaving something with the

twigs. I called up to them. They didn't answer. I called again,

louder.

'We are helping the stork!' shouted Marwan.

'Why?'

'We told you, storks are very lazy!'

Osman didn't show up for two days. On the way to the market,

I stopped at his home and tapped on the door. There was no

reply. I banged again and heard groaning inside.

'It's me,' I said. 'It's Tahir.'

The door was pulled back by a feeble hand. Osman peered

out, squinting into the light. His face was hung, his eyes ringed

with grey circles, his lips tightly shut.

'You look terrible,' I said.

Osman put a hand over his mouth.

'The dentist,' he mumbled.

'He came?'

'Mmmm.'

'Was it painful?'

A look of unimaginable fear swept over the guardian's face.

His entire body seemed to quiver. He struggled to stand up

straight.

'It was nothing to a man like me,' he said.

At the market I spotted the figure in the red cap again. This time

he wasn't moving, but standing across from me at a butcher's

stall. He had turned his back and was chatting to the butcher,

who passed him a cow's hoof. I stepped up and tapped his

shoulder. He turned. I froze.

It was Kamal.

I have never met someone so adept at hiding his emotions.

'Hello,' he said.

I was almost too shocked to speak.

'Are you . . . are you following me?' I said after a long delay.

Kamal passed the hoof back to the butcher and shook my hand.

'Good to see you,' he said.

I breathed in deep.

'And you.'

A few minutes later we were installed inside the window of a

smoky café opposite the Central Market. Kamal tugged off the

cap. His head was shaven clean bald. He could have passed for

fifty. He wasn't a day over twenty-eight.

'What have you been doing with yourself?'

He unwound the cellophane from a packet of Marlboros.

'Waiting,' he said.

'Waiting for what?'

'The right opportunity.'

'I knew our paths would cross again,' I said.

'Casablanca's very big but very small.'

'Did you get a job?'

Kamal flicked his ash on to the floor.

'A whole life change,' he said.

'Really?'

'Sure.'

'What?'

'I'm leaving Morocco.'

'Oh?'

'Yup.'

'Where are you going?'

'Down south.'

'To the Sahara?

'To Australia.'

'What are you going to do there?'

Kamal flicked his ash again, bit his lower lip.

'Start a family,' he said.

A month after our last breakfast at Café Napoleon, Kamal

had met an Australian backpacker at a hostel near the port.

He didn't say it, but he had been fishing for a foreigner, a passport

to a new life. She was a medical student, the daughter

of a property tycoon, and had been touring round the country

alone.

'She loves me,' he said.

'And do you love her?'

Kamal didn't answer right way. He paused as if to add a touch

of doubt.

'Sure I do,' he said.

I pressed a couple of coins on to the table and we shook hands.

As we shook, we looked at each other's eyes. I don't know about

him, but I was remembering the madcap adventures we had

shared. We left the café. Kamal put on his red baseball cap,

straightened it and stared at his watch. He crossed the street.

I have not seen him since.

Osman returned to work and showed off his new smile. The

other two guardians were envious, but too busy fretting about

the stork to make a point of it. The bird had flown away towards

the ocean and disappeared, despite the fact a ready-made nest

was awaiting it on our roof. Marwan said he and the others

knew a great deal about storks merely by being Moroccan, that

the birds were a national obsession.

Somewhere in my library I knew I had a book about African

birds. I went in search of it. When finally I found it, I flicked to

the page on Moroccan storks and read a passage to the guardians.

They weren't impressed.

'That's how you are,' said Osman scathingly.

'What do you mean?'

'In the West it's always like that.'

'Like what?'

'You read something in a book, some writing, and you think

you are an expert.'

'I'm not an expert,' I said.

'Osman's right,' said the Bear. 'Our knowledge isn't the kind

of thing you can find in a book. It's given to us through

generations of . . .'

'Of conversation,' said Marwan.

I went inside and slipped the book back in its place. The guardians

hardly knew it, but they had touched upon one of the greatest differences

between East and West. In the Occident learning tends to be done through reading,

while in the Orient the chain of transmission is made through generations

of accumulated conversation.

That night I took Ariane and Timur up for their bath. As they

splashed about, I told them never to take water for granted. I

described the desert, what it was like to sleep under the stars, and

how it felt to have the first rays of morning sunlight on your face.

'Baba, why do we live in Morocco?' Ariane suddenly asked.