In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" (57 page)

Read In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" Online

Authors: Phil Brown

Tags: #Social Science/Popular Culture

Prayer books from two orthodox hotels, the Pioneer Hotel in Greenfield Park and Lebowitz’s Pine View in Fallsburg. C

ATSKILLS

I

NSTITUTE

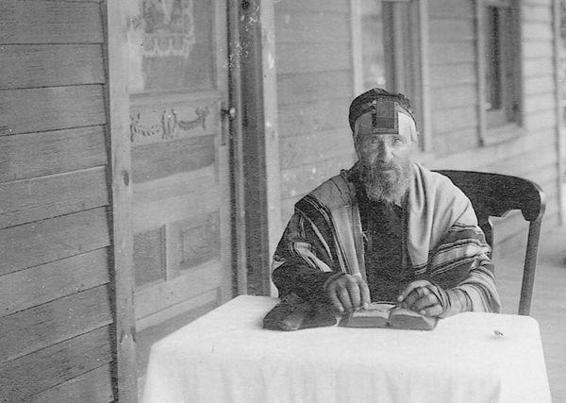

Itinerant rabbi looking for food and a place to sleep at the Beerkill Lodge in Greenfield Park, 1930s.

E

LOISE

K

ANFER

E

loise Kanfer, whose father built the Beerkill Lodge in Greenfield Park in the 1930s, lent me a photo to copy of an itinerant rabbi who came to the hotel looking for food and a place to sleep. In that fairly typical small hotel, where kosher food was served but the clientele was not orthodox, it was not seen as odd that this rabbi would hang around. After all, if the Catskills was the Jewish resort area, then all the elements found back home—in Europe or New York—could be found there as well. Virtually all Jewish hotels were kosher. Most had at least brief Friday night services, even if not many attended. ’Most every hotel I worked at had wine and challah on Shabbos, and many women lit candles on a special table, often in the card room. Observant orthodox hotels always existed; some still do. And today there are hundreds of orthodox and Hasidic summer camps, bungalow colonies, Yeshivas, and social service agencies. Hatzalah, the orthodox volunteer rescue squad/ambulance service, maintains a full branch there, and their publicly sold road map is the only map to pinpoint locations of hundreds of places. The Catskills was always a very Jewish place during the twentieth century, and for many less-observant and unobservant Jews it was an important source of Yiddishkeit and knowledge about religion.

Given that so much has been written about the Jewish experience in the Catskills, it is surprising that so little has been written about religion. The importance of religion is dealt with in my

Catskill Culture: A Mountain Rat’s Memories of the Great Jewish Resort Area

, Abraham Lavender and Clarence Steinberg’s

Jewish Farmers of the Catskills

, and Irwin Richman’s

Borscht Belt Bungalows

. Hasidic buyouts of hotels are the subject of Eileen Pollack’s

Paradise, New York

and Steve Gomer’s film,

Sweet Lorraine

, and the actuality of such buyouts is very evident from any drive in the Catskills. But though the dominant population is ultraorthodox Jews, there are no ethnographies or histories focused specifically on that culture.

Robert Eisenberg’s “Bungalow Summer,” from his collection

Boychiks in the Hood

, is a brief essay about the Hasidic and ultraorthodox communities that now represent the largest aspect of Jewish life in the Mountains. Among the stops on Eisenberg’s tour are the Lubavichers’ Ivy League Torah Program and a doctor’s office at Fialkoff’s Bungalow Colony (he doesn’t tell us, but there is a wonderful bakery there). He also reports on his visit to Elat Chayyim, the Jewish Renewal center in Accord that used to be Chait’s Hotel, where my mother was chef for a decade. Eisenberg’s essay ends with a trip to Monsey, halfway back to New York. Even though they are not about the Catskills, I kept those few pages because they make some interesting summary points.

Allegra Goodman’s “The Shul at Kaaterskill Falls,” from her novel

Kaaterskill Falls

, tells of an ultraorthodox community that has recently established its summer outpost in the eastern section of the northern Catskills. The location is far from any of the Jewish resort areas, and the book makes no mention of the resort industry. Still, for many readers it is informative about the contemporary orthodox culture in at least one part of the Catskills. Goodman’s characters are finely drawn, and she has a talent for portraying their psyches. One element in her setting is common to a number of Catskills communities—even though one sect dominates, there are interactions with other varieties of orthodoxy in the shul they all share.

Bungalow Summer:

The Catskills, New York

I

n 1969, I was sent to camp a few miles from the Pennsylvania-New York border. A couple of camp maintenance men, who spent their mornings picking up garbage and heaving it onto a truck while chanting “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, NLF is gonna win,” asked me if they could borrow my sleeping bag to take to a rock concert. When I finally saw them a week later, I asked for it back. “Oh, man, we lost it in the mud,” was their terse reply. The mud was Woodstock, and this summer, as every summer in the Catskills north of New York City, the hills are alive with the sound of Yiddish. Only this time the Hasidim are looking for solace amidst the ubiquitous signs of Woodstock II.

“Official Woodstock Guide Pick-up Site” announce placards above the cash registers at food and fuel outlets on the New York State Thruway. The guide itself is instructive. “What is love?” an attached coupon asks. “Do you love your music? Do you love playing in the mud with 250,000 strangers? Do you love pizza? Do you love your life? Woodstock ’94 and Pizza Hut.”

Are the furrow-browed rapacious businessmen who are putting on this brouhaha merely incarnations of the smooth-browed young men they once were, or have they metamorphosed into something new and more ominous? One thing’s for sure: The lanky young Hasid, his index finger absentmindedly scratching the base of his beard while he strolls across the lot of a McDonald’s at a roadside oasis, could care less. Nor could the two Hasidim in the back of a taxi ferrying them from South Fallsburg, epicenter of the Catskills summer bungalow colony scene, back to Boro Park—a trip that, the cab driver tells me while filling up his vehicle, runs them a tidy $175 each way.

“They’re in the diamond trade, you know,” the cab driver confides. “Most of them are, anyway. Diamonds may be a girl’s best friend, but they are also a cab driver’s.”

For those with more limited resources, there are bus services such as Emunah, which generally charges $110 per van load, each way, and provides a curtained aisle to separate men and women during prayer services. This can cause problems, and in recent months a Russian émigre by the name of Sima Rabinowicz refused to relinquish her seat on the men’s side of the aisle so that they could commence their supplications. She took her case to the New York Civil Liberties Union, which is representing her in court. In the meantime, men who share the bus with Sima have it stop and wait while they debark and

daven

.

At this time of the year, the permanent Hasidic population north of New York City swells from around 20,000 to well over 50,000, as eager refugees from the urban battlefield take up residence in bungalow colonies and retreats, which are often little more than clusters of shacks centered around threadbare quads sprinkled throughout the several-thousand-square-mile area that constitutes the Catskill region. For a family from Williamsburg or Crown Heights, these meager resorts tucked away in mountain hollows amid thick growths of deciduous trees are often the closest thing they will get to a vacation.

Encroaching on the bungalow colonies are a burgeoning number of camps for children and more conventional hotels. Most are modest, but some resorts approach a level of luxury that would meet the standards of even the most jaded traveler. But whatever the mode of accommodation, a certain cadence of daily activity that cuts across all socioeconomic boundaries unites everyone. Most of the day is taken up with study, preparing and eating meals, a bit of idle socializing, with a minimum of organized physical activity, and none of the planned diversions that would be offered at other resorts.

The Catskills and points south, nearer the city, are not only known for the Hasidic influx, but also for the proliferation of New Age retreats. South Fallsburg alone boasts two ashrams, one of which is run by a Jewish swami, and there is the Foundation for the Course in Miracles, a Christian organization with a former Jew at its helm. There is also a retreat center run by a reconstituted group of Jews that sees itself as the next big leap forward in the evolution of Judaism and proudly wears the label of “neo-Hasidic.” It is Elat Chayyim, the Woodstock Center for Healing and Renewal, an outgrowth of Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi’s Philadelphia-based P’nai Or, and it holds seminars on such subjects as “Jewish Liberation Theology” and “Exploring Jewish Prayer” against a picture-postcard backdrop of farmhouses and mountain trails.

Part of an even larger movement called Jewish Renewal, the Woodstock Center and the ideas from which it is spawned have attracted thousands of adherents in recent years. Rabbi Schachter, its central figure, is the Polish-born son of a Belzer Hasid; he grew up in Vienna, where he attended both a traditional

yeshiva

and a left-wing Zionist high school. This eclectic mix produced a singularly iconoclastic and controversial thinker.

Schachter received his

smicha

, or ordination certificate, from the Lubavitch yeshiva in Brooklyn in 1947, having fled Europe via Morocco some years earlier. Afterward he took on a number of assignments, including a pulpit in Winnipeg, and finally ended up in Philadelphia, where he developed nothing less than his own offshoot of Judaism, a new strand of thought whose central objective revolves around making prayer, rituals, and commandments more meaningful to the contemporary spirit.

The father of ten children, Rabbi Schachter—or Zalman, as he is more commonly referred to—has lectured and studied with native American elders, Buddhist lamas, Catholic theologians, and guru Baba Ram Dass. He has been called everything from a charlatan to a saint. As for his being neo-Hasidic, that is something open to debate. “Neo” as a prefix is pregnant with possibilities, and it may or may not apply to the teachings of Zalman. Just as Herbert Marcuse was a neo-Marxist, Irving Kristol a neo-Conservative, and members of Nirvana were neo-hippies, the philosophy espoused by Schachter may be arguably neo-Hasidic. But as far as any strict resemblance to conventional Hasidism goes, Zalman Schachter is to the Lubavitcher Rebbe what the Beastie Boys are to Steve and Edie.

The charismatic troika that runs the Elat Chayyim retreat consists of Zalman, Arthur Waskow, a rabbi out of the Reconstructionist mold from Philadelphia, and a younger disciple of Zalman’s, Rabbi Jeff Roth. This is not to suggest that the set-up is in the least bit patriarchal. Most of the remaining positions of responsibility seem to be occupied by women, and the rabbis often defer to them during services.

Elat Chayyim operates out of a rented lodge, Su Casa, situated in the hilly vicinity of Woodstock. The main dining room serves up three sumptuous vegetarian meals a day, which are accompanied by lively discussion and debate. Upon walking into the unadorned mess hall, one is confronted with the sight of perhaps 150 people, most of them Jews in their forties, at least 80 percent of whom are female. At first glance, I feel like I’ve stumbled onto the food concessions pavilion at a Holly Near festival. Many of the guests, savoring a typical meal of spanikopita, pesto, eggplant parmigiana, and brown rice, seem to be products of the antiwar movement.

The couple I sit next to have between them made it to Woodstock, the Mobilization Against the War demonstration in Washington, and the militant May Day protests. A man across the table from me, who hails from Berkeley, strenuously attempts to convey the Hasidic nature of the movement. Jewish Renewal is true Hasidism, he asserts. It is the New American Hasidism because it incorporates the concepts of pluralism, egalitarianism, and feminism, as well as respect for Native American culture and sympathy for the Palestinians. The latter have suffered more than the Jews, he argues somewhat incredibly.