Influence: Science and Practice (24 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Study Questions

Content Mastery

- Why do we want to look and be consistent in most situations?

- Why do we find even rigid, stubborn consistency desirable in many situations?

- Which four factors cause a commitment to affect a person’s self-image and consequent future action?

- What makes written commitments so effective?

- What is the relationship between the compliance tactic of low-balling and the term “growing its own legs”?

Critical Thinking

- Suppose you were advising American soldiers on a way to avoid consistency pressures like those used to gain collaboration from the POWs during the Korean War. What would you tell them?

- In referring to the fierce loyalty of Harley-Davidson motorcycle owners, one commentator has said, “if you can persuade your customers to tattoo your name on their chests, you’ll probably never have to worry about them shifting brands.” Explain why this would be true. In your answer, make reference to each of the four factors that maximize the power of a commitment on future action.

- Imagine that you are having trouble motivating yourself to study for an important exam that is less than a week away. Drawing upon your knowledge of the commitment process, describe what you would do to get yourself to put in the necessary study time. Be sure to explain why your chosen actions ought to work.

- Think about the traditional large wedding ceremony that is characteristic of most cultures. Which features of that kind of event can be seen as commitment-enhancing devices for the couple and their families?

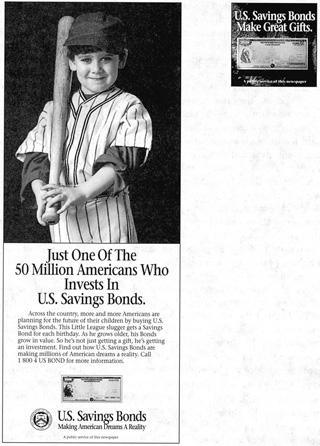

- How does the photograph that opens this chapter reflect the topic of the chapter?

Chapter 4

Social Proof

Truths Are Us

Where all think alike, no one thinks very much.

—Walter Lippmann

I

DON’T KNOW ANYONE WHO LIKES CANNED LAUGHTER. IN FACT

, when I surveyed the people who came into my office one day—several students, two telephone repairmen, a number of university professors, and the janitor—the reaction was invariably critical. Television, with its incessant system of laugh tracks and technically augmented mirth, received the most heat. The people I questioned hated canned laughter. They called it stupid, phony, and obvious. Although my sample was small, I would bet that it closely reflects the negative feelings of most of the American public toward laugh tracks.

Why, then, is canned laughter so popular with television executives? They have won their exalted positions and splendid salaries by knowing how to give the public what it wants. Yet they religiously employ the laugh tracks that their audiences find distasteful, and they do so over the objections of many of their most talented artists. It is not uncommon for acclaimed directors, writers, or actors to demand the elimination of canned responses from the television projects they undertake. These demands are only sometimes successful, and when they are, it is not without a battle.

What can it be about canned laughter that is so attractive to television executives? Why are these shrewd and tested people championing a practice that their potential watchers find disagreeable and their most creative talents find personally insulting? The answer is both simple and intriguing: They know what the research says. Experiments have found that the use of canned merriment causes an audience to laugh longer and more often when humorous material is presented and to rate the material as funnier (Provine, 2000). In addition, some evidence indicates that canned laughter is most effective for poor jokes (No-sanchuk & Lightstone, 1974).

In light of these data, the actions of television executives make perfect sense. The introduction of laugh tracks into their comic programming increases the humorous and appreciative responses of an audience, even—and especially—when the material is of poor quality. Is it any surprise, then, that television, glutted as it is with artless situation-comedies, is saturated with canned laughter? Those executives know precisely what they are doing.

With the mystery of the widespread use of laugh tracks solved, we are left with a more perplexing question: Why does canned laughter work on us the way it does? It is no longer the television executives who appear peculiar; they are acting logically and in their own interests. Instead, it is the behavior of the audience that seems strange. Why should we laugh more at comedy material afloat in a sea of mechanically fabricated merriment? And why should we think that comic flotsam funnier? The executives aren’t really fooling us. Anyone can recognize dubbed laughter. It is so blatant, so clearly counterfeit, that there can be no confusing it with the real thing. We know full well that the hilarity we hear is irrelevant to the humorous quality of the joke it follows, is created not spontaneously by a genuine audience but artificially by a technician at a control board. Yet, transparent forgery that it is, it works on us!

The Principle of Social Proof

To discover why canned laughter is so effective, we first need to understand the nature of yet another potent weapon of influence: the principle of social proof. This principle states that we determine what is correct by finding out what other people think is correct (Lun et al., 2007). The principle applies especially to the way we decide what constitutes correct behavior.

We view a behavior as correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it.

The tendency to see an action as appropriate when others are doing it works quite well normally. As a rule, we will make fewer mistakes by acting in accord with social evidence than by acting contrary to it. Usually, when a lot of people are doing something, it is the right thing to do. This feature of the principle of social proof is simultaneously its major strength and its major weakness. Like the other weapons of influence, it provides a convenient shortcut for determining the way to behave but, at the same time, makes one who uses the shortcut vulnerable to the attacks of profiteers who lie in wait along its path.

In the case of canned laughter, the problem comes when we begin responding to social proof in such a mindless and reflexive fashion that we can be fooled by partial or fake evidence. Our folly is not that we use others’ laughter to help decide what is humorous; that is in keeping with the well-founded principle of social proof. The folly is that we do so in response to patently fraudulent laughter. Somehow, one disembodied feature of humor—a sound—works like the essence of humor. The example from

Chapter 1

of the turkey and the polecat is instructive. Because the peculiar cheep-cheep of turkey chicks is normally associated with newborn turkeys, their mothers will display or withhold maternal care solely on the basis of that sound. Remember how, consequently, it was possible to fool a mother turkey with a stuffed polecat as long as the replica played the recorded cheep-cheep of a baby turkey. The simulated chick sound was enough to start the mother turkey’s maternal tape whirring.

The lesson of the turkey and the polecat illustrates uncomfortably well the relationship between the average viewer and the laugh-track-playing television executive. We have become so accustomed to taking the humorous reactions of others as evidence of what deserves laughter that we too can be made to respond to the sound, and not the substance, of the real thing. Much as a cheep-cheep noise removed from the reality of a chick can stimulate a female turkey to mother, so can a recorded ha-ha removed from the reality of a genuine audience stimulate us to laugh. The television executives are exploiting our preference for shortcuts, our tendency to react automatically on the basis of partial evidence. They know that their tapes will cue our tapes.

Click

,

whirr

.

People Power

Television executives are hardly alone in their use of social evidence for profit. Our tendency to assume that an action is more correct if others are doing it is exploited in a variety of settings. Bartenders often salt their tip jars with a few dollar bills at the beginning of an evening to simulate tips left by prior customers and thereby to give the impression that tipping with folding money is proper barroom behavior. Church ushers sometimes salt collection baskets for the same reason and with the same positive effect on proceeds. Evangelical preachers are known to seed their audience with ringers, who are rehearsed to come forward at a specified time to give witness and donations.

Advertisers love to inform us when a product is the “fastest-growing” or “largest-selling” because they don’t have to convince us directly that the product is good; they need only say that many others think so, which seems proof enough. The producers of charity telethons devote inordinate amounts of time to the incessant listing of viewers who have already pledged contributions. The message being communicated to the holdouts is clear: “Look at all the people who have decided to give. It

must

be the correct thing to do.” Certain nightclub owners manufacture a brand of visible social proof for their clubs’ quality by creating long waiting lines outside when there is plenty of room inside. Salespeople are taught to spice their pitches with numerous accounts of individuals who have purchased the product. Sales and motivation consultant Cavett Robert captures the principle nicely in his advice to sales trainees: “Since 95 percent of the people are imitators and only 5 percent initiators, people are persuaded more by the actions of others than by any proof we can offer.”

Researchers, too, have employed procedures based on the principle of social proof—sometimes with astounding results.

1

One psychologist in particular, Albert Bandura, has led the way in developing such procedures to eliminate undesirable behavior. Bandura and his colleagues have shown how people suffering from phobias can be rid of these extreme fears in an amazingly simple fashion. For instance, in an early study (Bandura, Grusec, & Menlove, 1967), nursery-school-age children, chosen because they were terrified of dogs, merely watched a little boy playing happily with a dog for 20 minutes a day. This exhibition produced such marked changes in the reactions of the fearful children that, after only four days, 67 percent of them were willing to climb into a playpen with a dog and remain confined there petting and scratching the dog while everyone else left the room. Moreover, when the researchers tested the children’s fear levels again, one month later, they found that the improvement had not diminished during that time; in fact, the children were more willing than ever to interact with dogs. An important practical discovery was made in a second study of children who were exceptionally afraid of dogs (Bandura & Menlove, 1968): To reduce these children’s fears, it was not necessary to provide live demonstrations of another child playing with a dog; film clips had the same impact. The most effective clips were those depicting a variety of other children interacting with their dogs. Apparently, the principle of social proof works best when the proof is provided by the actions of many other people.

2

1

A program of investigation conducted by Kenneth Craig and his associates demonstrates how the experience of pain can be affected by the principle of social proof. In one study (Craig & Prkachin, 1978), subjects who received a series of electric shocks felt less pain (as indicated by self-reports, psychophysical measures of sensory sensitivity, and such physiological responses as heart rate and skin conductivity) when they were in the presence of another subject who was tolerating the shocks as if they were not painful.

2

Any reader who doubts that the seeming appropriateness of an action is importantly influenced by the number of others performing it might try a small experiment. Stand on a busy sidewalk, pick an empty spot in the sky or on a tall building, and stare at it for a full minute. Very little will happen around you during that time—most people will walk past without glancing up, and virtually no one will stop to stare with you. Now, on the next day, go to the same place and bring along four friends to look upward too. Within 60 seconds, a crowd of passersby will have stopped to crane their necks skyward with the group. For those pedestrians who do not join you, the pressure to look up at least briefly will be nearly irresistable; if the results of your experiment are like those of one performed by three social psychologists in New York, you and your friends will cause 80 percent of all passersby to lift their gaze to your empty spot (Milgram, Bickman, & Berkowitz, 1969).

Fifty Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong