Influence: Science and Practice (34 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

What is interesting is that the customers appear to be fully aware of the liking and friendship pressures embodied in the Tupperware party. Some don’t seem to mind; others do, but don’t seem to know how to avoid these pressures. One woman I spoke with described her reactions with more than a bit of frustration in her voice.

It’s gotten to the point now where I hate to be invited to Tupperware parties. I’ve got all the containers I need; and if I wanted any more, I could buy another brand cheaper in the store. But when a friend calls up, I feel like I have to go. And when I get there, I feel like I have to buy something. What can I do? It’s for one of my friends.

With so irresistible an ally as friendship, it is little wonder that the Tupperware Corporation has abandoned retail sales outlets and is pushing the home party concept. For example, in 2003 the Tupperware corporation did something that would defy logic for almost any other business: It severed its relationship with the retailer Target Stores because sales of their products at Target locations were too strong! As a consequence, the partnership had to be ended because of its detrimental effect on the number of home parties that could be arranged (Latest News, 2003). Statistics reveal that a Tupperware party now starts somewhere every 2.7 seconds. Of course, all sorts of other compliance professionals recognize the pressure to say yes to someone we know and like. Take, for instance, the growing number of charity organizations that recruit volunteers to canvass for donations close to their own homes. They understand perfectly how much more difficult it is for us to turn down a charity request when it comes from a friend or neighbor.

Other compliance professionals have found that the friend doesn’t even have to be present to be effective; often, just the mention of the friend’s name is enough. The Shaklee Corporation, which specializes in door-to-door sales of various home-related products, advises its salespeople to use the “endless chain” method for finding new customers. Once a customer admits that he or she likes a product, that customer can be pressed for the names of friends who would also appreciate learning about it. The individuals on that list can then be approached for sales

and

a list of their friends, who can serve as sources for still other potential customers, and so on in an endless chain.

The Home Party

At home parties, like this Tupperware-style party for a line of eco-friendly cleaning products, the bond that exists between the party goers and the party hostess usually seals the sales.

The Liking Rule

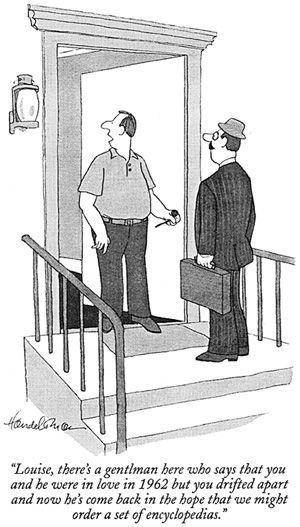

Love and encyclopedia sales are forever.

© The New Yorker Collection 1982, by J. B. Handelsman, from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

The key to the success of this method is that each new prospect is visited by a salesperson armed with the name of a friend “who suggested I call on you.” Turning the salesperson away under those circumstances is difficult; it’s almost like rejecting the friend. The Shaklee sales manual insists that employees use this system: “It would be impossible to overestimate its value. Phoning or calling on a prospect and being able to say that Mr. So-and-so, a friend of his, felt he would benefit by giving you a few moments of his time is virtually as good as a sale 50 percent made before you enter.”

Making Friends to Influence People

Compliance practitioners’ widespread use of the liking bond between friends tells us much about the power of the liking rule to produce assent. In fact, we find that such professionals seek to benefit from the rule even when already formed friendships are not present for them to employ. Under these circumstances, the professionals still make use of the liking bond by employing a compliance strategy that is quite direct: They first get us to like

them

.

READER’S REPORT 5.1

From a Chicago Man

Although I’ve never been to a Tupperware Party, I recognized the same kind of friendship pressures recently when I got a call from a long distance phone company saleswoman. She told me that one of my buddies had placed my name on something called the “MCI Friends and Family Calling Circle.”

This friend of mine, Brad, is a guy I grew up with but who moved to New Jersey last year for a job. He still calls me pretty regularly to get the news on the guys we used to hang out with. The saleswoman told me that he could save 20 percent on all the calls he made to the people on his Calling-Circle list, provided they are MCI phone company subscribers. Then she asked me if I wanted to switch to MCI to get all the blah, blah, blah benefits of MCI service, and so that Brad could save 20 percent on his calls to me.

Well, I couldn’t have cared less about the benefits of MCI service; I was perfectly happy with the long distance company I had. But the part about wanting to save Brad money on our calls really got to me. For me to say that I didn’t want to be in his Calling Circle and didn’t care about saving him money would have sounded like a real affront to our friendship when he heard about it. So, to avoid insulting him, I told her to switch me to MCI.

I used to wonder why women would go to a Tupperware Party just because a friend was holding it, and then buy stuff they didn’t want once they were there. I don’t wonder anymore.

Author’s note:

This reader is not alone in being able to testify to the power of the pressures embodied in MCI’s Calling Circle idea. When

Consumer Reports

magazine inquired into the practice, the MCI salesperson they interviewed was quite succinct: “It works 9 out of 10 times,” he said.

There is a man in Detroit, Joe Girard, who specialized in using the liking rule to sell Chevrolets. He became wealthy in the process, making hundreds of thousands dollars a year. With such a salary, we might guess that he was a high-level GM executive or perhaps the owner of a Chevrolet dealership. But no. He made his money as a salesman on the showroom floor. He was phenomenal at what he did. For twelve years straight, he won the title of “Number One Car Salesman”; he averaged more than five cars and trucks sold every day he worked; and he has been called the world’s “greatest car salesman” by the

Guinness Book of World Records

.

For all his success, the formula he employed was surprisingly simple. It consisted of offering people just two things: a fair price and someone they liked to buy from. “And that’s it,” he claimed in an interview. “Finding the salesman you like, plus the price. Put them both together, and you get a deal.”

Fine. The Joe Girard formula tells us how vital the liking rule is to his business, but it doesn’t tell us nearly enough. For one thing, it doesn’t tell us why customers liked him more than some other salesperson who offered a fair price. There is a crucial—and fascinating—general question that Joe’s formula leaves unanswered. What are the factors that cause one person to like another? If we knew

that

answer, we would be a long way toward understanding how people such as Joe can so successfully arrange to have us like them and, conversely, how we might successfully arrange to have others like us. Fortunately, social scientists have been asking this question for decades. Their accumulated evidence has allowed them to identify a number of factors that reliably cause liking. As we will see, each is cleverly used by compliance professionals to urge us along the road to “yes.”

Why Do I Like You? Let Me List the Reasons

Physical Attractiveness

Although it is generally acknowledged that good-looking people have an advantage in social interaction, recent findings indicate that we may have sorely underestimated the size and reach of that advantage. There seems to be a

click

,

whirr

response to attractive people (Olson & Marshuetz, 2005). Like all

click

,

whirr

reactions, it happens automatically, without forethought. The response itself falls into a category that social scientists call

halo effects

. A halo effect occurs when one positive characteristic of a person dominates the way that person is viewed by others. The evidence is now clear that physical attractiveness is often such a characteristic.

Research has shown that we automatically assign to good-looking individuals such favorable traits as talent, kindness, honesty, and intelligence (for a review of this evidence, see Langlois et al., 2000). Furthermore, we make these judgments without being aware that physical attractiveness plays a role in the process. Some consequences of this unconscious assumption that “good-looking equals good” scare me. For example, a study of the 1974 Canadian federal elections found that attractive candidates received more than two and a half times as many votes as unattractive candidates (Efran & Patterson, 1976). Despite such evidence of favoritism toward handsome politicians, follow-up research demonstrated that voters did not realize their bias. In fact, 73 percent of Canadian voters surveyed denied in the strongest possible terms that their votes had been influenced by physical appearance; only 14 percent even allowed for the possibility of such influence (Efran & Patterson, 1976). Voters can deny the impact of attractiveness on electability all they want, but evidence has continued to confirm its troubling presence (Budesheim & DePaola, 1994).

A similar effect has been found in hiring situations. In one study, good grooming of applicants in a simulated employment interview accounted for more favorable hiring decisions than did job qualifications—this, even though the interviewers claimed that appearance played a small role in their choices (Mack & Rainey, 1990). The advantage given to attractive workers extends past hiring day to payday. Economists examining U.S. and Canadian samples have found that attractive individuals get paid an average of 12–14 percent more than their unattractive coworkers (Hammermesh & Biddle, 1994).

Equally unsettling research indicates that our judicial process is similarly susceptible to the influences of body dimensions and bone structure. It now appears that good-looking people are likely to receive highly favorable treatment in the legal system (see Castellow, Wuensch, & Moore, 1991; and Downs & Lyons, 1990, for reviews). For example, in a Pennsylvania study (Stewart, 1980), researchers rated the physical attractiveness of 74 separate male defendants at the start of their criminal trials. When, much later, the researchers checked court records for the results of these cases, they found that the handsome men had received significantly lighter sentences. In fact, attractive defendants were twice as likely to avoid jail as unattractive defendants.

1

In another study—this one on the damages awarded in a staged negligence trial—a defendant who was better looking than his victim was assessed an average amount of $5,623; but when the victim was the more attractive of the two, the average compensation was $10,051. What’s more, both male and female jurors exhibited the attractiveness-based favoritism (Kulka & Kessler, 1978).

1

This finding—that attractive defendants, even when they are found guilty, are less likely to be sentenced to prison—helps explain one fascinating experiment in criminology (Kurtzburg, Safar, & Cavior, 1968). Some New York City jail inmates with facial disfigurements underwent plastic surgery while incarcerated; other inmates with similar disfigurements did not. Furthermore, some members of each group received services (such as counseling, training, etc.) designed to rehabilitate them to society. One year after the inmates had been released from jail, a check of the records revealed that (except for heroin addicts) criminals given the cosmetic surgery were significantly less likely to have returned to jail. The most interesting feature of this finding was that it was equally true for those inmates who had not received the traditional rehabilitative services and for those who had. Apparently, some criminologists then argued that when it comes to ugly inmates, prisons would be better off to abandon the costly rehabilitation services they typically provide and offer plastic surgery instead; the surgery seems to be at least as effective and decidedly less expensive.