Influence: Science and Practice (32 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Because automatic pilots can be engaged and disengaged at will, we can cruise along trusting in the course steered by the principle of social proof

until

we recognize that inaccurate data are being used. Then we can take the controls, make the necessary correction for the misinformation, and reset the automatic pilot. The transparency of the rigged social proof we get these days provides us with exactly the cue we need for knowing when to perform this simple maneuver. With no more cost than a bit of vigilance for plainly counterfeit social evidence, then, we can protect ourselves nicely.

READER’S REPORT 4.3

From a Central American Marketing Executive

I’ve been reading your book

Influence

. I’m a marketer, and the book has helped me see how certain kinds of techniques work. As I read the third chapter, about social proof, I recognized an interesting example.

In my country, Ecuador, you can hire a person or groups of people (consisting traditionally of women) to come to the funeral of a family member or friend. The job of these people is to cry while the dead person is being buried, making, for sure, more people start to cry. This job was quite popular a few years ago, and the well known people that worked in this job received the name of “lloronas,” which means criers.

Author’s note:

We can see how, at different times and in different cultures, it has been possible to profit from manufactured social proof—even when that proof has been plainly manufactured. This possibility has now advanced into the digital age through the computer-generated voices employed by many modern merchandisers. One study showed that people who listened to five positive book reviews from real Amazon.com customers became significantly more favorable toward the book if the reviews were “spoken” by five separate (obviously) synthesized voices than if they’d heard these five reviews via one (obviously) synthesized voice (Lee & Nas, 2004).

Let’s take an example. A bit earlier, I noted the proliferation of average person-on-the-street ads, in which a number of ordinary people speak glowingly of a product, often without knowing that their words are being recorded. As would be expected according to the principle of social proof, these testimonials from “average people like you and me” make for quite effective advertising campaigns. They have always included a relatively subtle kind of distortion: We hear only from those who like the product; as a result, we get an understandably biased picture of the amount of social support for it. More recently, though, a cruder and more unethical sort of falsification has been introduced. Commercial producers often don’t bother to get genuine testimonials. They merely hire actors to play the roles of average people testifying in an unrehearsed fashion to an interviewer. It is amazing how bald-faced these “unrehearsed interview” commercials can be. (See the example in

Figure 4.4

.) The situations are obviously staged, the participants are clearly actors, and the dialogue is unmistakably prewritten.

Figure 4.4

Just Your Average Martian on the Street

Apparently I’m not alone in noticing the number of blatantly phony “unrehearsed” testimonial ads these days. Humorist Dave Barry has registered their prevalence too and has labeled their inhabitants

Consumers from Mars

, which is a term I like and have even begun using myself. It helps remind me that, as regards my buying habits, I should be sure to ignore the tastes of these individuals who, after all, come from a different planet than I do.

I know that whenever I encounter an influence attempt of this sort, it sets off in me a kind of alarm with a clear directive:

Attention! Attention! Bad social proof in this situation. Temporarily disconnect automatic pilot

. It’s so easy to do. We need only make a conscious decision to be alert to counterfeit social evidence. We can relax until the exploiters’ evident fakery is spotted, at which time we can pounce.

And we should pounce with a vengeance. I am speaking of more than simply ignoring the misinformation, although this defensive tactic is certainly called for. I am speaking of aggressive counterattack. Whenever possible we ought to sting those responsible for the rigging of social evidence. We should purchase no products featured in phony “unrehearsed interview” commercials. Moreover, each manufacturer of the items should receive a letter explaining our response and recommending that they discontinue use of the advertising agency that produced so deceptive a presentation of their product.

Of course, we don’t always want to trust the actions of others to direct our conduct—especially in a situation important enough to warrant our personal investigation of the pros and cons, or one in which we are experts—but we do want to be able to count on others’ behavior as a source of valid information in a wide range of settings. If we find in such settings that we cannot trust the information to be valid because someone has tampered with the evidence, we ought to be ready to strike back. In such instances, I personally feel driven by more than an aversion to being duped. I bristle at the thought of being pushed into an unacceptable corner by those who would use one of my hedges against the decisional overload of modern life against me. And I get a genuine sense of righteousness by lashing out when they try. If you are like me—and many others like me—so should you.

Looking Up

In addition to the times when social evidence is deliberately faked, there is another time when the principle of social proof will regularly steer us wrong. In such an instance, an innocent, natural error will produce snowballing social proof that pushes us to an incorrect decision. The pluralistic ignorance phenomenon, in which everyone at an emergency sees no cause for alarm, is one example of this process.

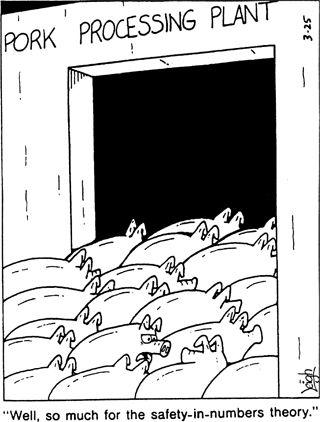

“Shakin’ Bacon”

The notion that there is safety in numbers can prove very wrong once a herd mentality sets in.

By permission of Leigh Rubin and Creators Syndicate, Inc..

The best illustration I know, however, comes from Singapore, where a few years ago, for no good reason, customers of a local bank began drawing out their money in a frenzy. The run on this respected bank remained a mystery until much later, when researchers interviewing participants discovered its peculiar cause: An unexpected bus strike had created an abnormally large crowd waiting at the bus stop in front of the bank that day. Mistaking the gathering for a crush of customers poised to withdraw their funds from a failing bank, passersby panicked and got in line to withdraw their deposits, which led more passersby to do the same. Soon after opening its doors, the bank was forced to close to prevent a complete crash (“News,” 1988).

6

6

It is perhaps no accident that this event took place in Singapore, as research tells us that citizens of Far Eastern societies have a greater tendency to respond to social proof information that do those from Western cultures (Bond & Smith, 1996). But, any culture that values the group over the individual exhibits this greater susceptibility to information about peers’ choices. A few years ago, some of my colleagues and I showed how this tendency operated in Poland, a country whose population is moving toward Western values but still retains a more communal orientation than average Americans. We asked college students in Poland and the United States whether they would be willing to participate in a marketing survey. For the American students, the best predictor of their decision was information about how often they, themselves, had agreed to marketing survey requests in the past; this is in keeping with the primarily individualistic point of reference of most Americans. For the Polish students, however, the best predictor of their decisions was information about how often their friends had agreed to marketing survey requests in the past; this is in keeping with the more collectivistic values of their nation (Cialdini et al., 1999).

This account provides certain insights into the way we respond to social proof. First, we seem to assume that if a lot of people are doing the same thing, they must know something we don’t. Especially when we are uncertain, we are willing to place an enormous amount of trust in the collective knowledge of the crowd. Second, quite frequently the crowd is mistaken because its members are not acting on the basis of any superior information but are reacting, themselves, to the principle of social proof.

There is a lesson here: An automatic pilot device, like social proof, should never be trusted fully; even when no saboteur has slipped misinformation into the mechanism, it can sometimes go haywire by itself. We need to check the machine from time to time to be sure that it hasn’t worked itself out of sync with the other sources of evidence in the situation—the objective facts, our prior experiences, our own judgments. Fortunately, this precaution requires neither much effort nor much time. A quick glance around is all that is needed. And this little precaution is well worth it. The consequences of single-minded reliance on social evidence can be frightening. For instance, a masterful analysis by aviation safety researchers has uncovered an explanation for the misguided decisions of many pilots who crashed while attempting to land planes after weather conditions had become dangerous: The pilots hadn’t focused sufficiently on the mounting physical evidence for aborting a landing. Instead, they had focused too much on the mounting social evidence for attempting one—the fact that each in a line of prior aircraft had landed safely (Facci & Kasarda, 2004).

Certainly, a flier following a line of others would be wise to glance occasionally at the instrument panel and out the window. In the same way, we need to look up and around periodically whenever we are locked into the evidence of the crowd. Without this simple safeguard against misguided social proof, our outcomes might well run parallel to those of the unfortunate pilots and the Singapore bank: crash.

READER’S REPORT 4.4

From a Former Racetrack Employee

I became aware of one method of faking social evidence to one’s advantage while working at a racetrack. In order to lower the odds and make more money, some bettors are able to sway the public to bet on bad horses.

Odds at a racetrack are based on where the money is being bet. The more money on a horse, the better the odds. Many people who play the horses have surprisingly little knowledge of racing or betting strategy. Thus, especially when they don’t know much about the horses in a particular race, a lot of times they’ll simply bet the favorite. Because tote boards display up-to-the-minute odds, the public can always tell who the current favorite is. The system that a high roller can use to alter the odds is actually quite simple. The guy has in mind a horse he feels has a good chance of winning. Next he chooses a horse that has long odds (say, 15 to 1) and doesn’t have a realistic chance to win. The minute the mutual windows open, the guy puts down $100 on the inferior horse, creating an instant favorite whose odds on the board drop to about 2 to 1.

Now the elements of social proof begin to work. People who are uncertain of how to bet the race look to the tote board to see which horse the early bettors have decided is a favorite, and they follow. A snowballing effect now occurs as other people continue to bet the favorite. At this point, the high roller can go back to the window and bet heavily on his true favorite, which will have better odds now because the “new favorite” has been pushed down the board. If the guy wins, the initial $100 investment will have been worth it many times over.

I’ve seen this happen myself. I remember one time a person put down $100 on a pre-race 10 to 1 shot, making it the early favorite. The rumors started circulating around the track—the early bettors knew something. Next thing you know, everyone (myself included) was betting on this horse. It ended up running last and had a bad leg. Many people lost a lot of money. Somebody came out ahead, though. We’ll never know who. But he is the one with all the money. He understood the theory of social proof.