Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (11 page)

Still, they were neither as talented nor as artistic as the Austrians, and the Ostmark dominated the reconciliation game. Fact has become rather obscured by subsequent myths, but what is clear is that Sindelar missed a series of chances in the first half. Given how frequently he rolled the ball a fraction wide of the posts, even contemporary reports wondered whether he had been mocking the Germans - and supposed orders not to score - by missing on purpose. Eventually, midway through the second half, he knocked in a rebound, and when his friend Schasti Sesta looped a second from a free-kick, he celebrated by dancing in front of a directors’ box packed with high-ranking Nazis.

In the months that followed, Sindelar, who never made any secret of his Social Democratic leanings, repeatedly refused to play for Sepp Herberger’s united German team. In the August he bought a café from Leopold Drill, a Jew forced to give it up under new legislation - paying DM20,000, which was either a very fair price or disgracefully opportunistic, depending which account you choose to believe - and was censured by the authorities for his reluctance to put up Nazi posters. To claim he was a dissident, though, as some have done, is to take things too far.

On the morning of 23 January 1939, his friend Gustav Hartmann, looking for Sindelar, broke down the door of a flat on Annagasse. He found him, naked and dead, lying alongside the unconscious form of his girlfriend of ten days, Camilla Castignola. She died later in hospital, the victim, like Sindelar, of carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a faulty heater.

Or at least that was what the police said, as they ended their enquiries after two days. The public prosecutor, though, had still not reached a conclusion six months later when the Nazi authorities ordered the case be closed. In a 2003 BBC documentary, Egon Ulbrich, a friend of Sindelar, claimed a local official was bribed to record his death as an accident, which ensured that he would receive a state funeral. Others came up with their own explanations. On 25 January, a piece in the Austrian newspaper

Kronen Zeitung

claimed that ‘everything points towards this great man having become the victim of murder through poisoning’. In his ‘Ballad on the Death of a Footballer’, Torberg suggested suicide by a man who felt ‘disowned’ by ‘the new order’. There were later suggestions that Sindelar or Castignola or both were Jewish. It is true that Sindelar played for Austria Vienna, the club of the Jewish bourgeoisie, and had been born in Moravia, from where many Jews had emigrated to the capital, but his family was Catholic. It is just about conceivable that Castignola, an Italian, may have had Jewish origins, but they were well-enough hidden that she had been allowed to become co-owner of a bar in the week before her death. Most tellingly, neighbours had complained a few days earlier that one of the chimneys in the block was defective.

The available evidence suggests Sindelar’s death was an accident, and yet the sense that heroes cannot mundanely die prevailed. What, after all, at least to a romantic liberal mind, could better symbolise Austria at the point of the Anschluss than this athlete-artist, the darling of Viennese society, being gassed alongside his Jewish girlfriend? ‘The good Sindelar followed the city, whose child and pride he was, to its death,’ Polgar wrote in his obituary. ‘He was so inextricably entwined with it that he had to die when it did. All the evidence points to suicide prompted by loyalty to his homeland. For to live and play football in the downtrodden, broken, tormented city meant deceiving Vienna with a repulsive spectre of itself… But how can one play football like that? And live, when a life without football is nothing?’

To its end, the football of the coffee house remained heroically romantic.

Chapter Five

Organised Disorder

∆∇ The football boom came late to the USSR and, perhaps because of that, it rapidly took on a radical aspect, uninhibited by historically rooted notions of the ‘right’ way of doing things. British sailors had played the game by the docks in Odessa as early as the 1860s, a description in

The Hunter

magazine giving some idea of the chaos and physicality of the game. ‘It is played by people with solid muscles and strong legs - a weak one would only be an onlooker in such a mess,’ their reporter wrote, apparently both bemused and disapproving.

It was only in the 1890s that the sport began to be properly organised. In Russia, as in so many other places, the British had a decisive role, first in St Petersburg, and later in Moscow, where Harry Charnock, general manager of the Morozov Mills, established the club that would become Dinamo Moscow in an attempt to persuade his workers to spend their Saturdays doing something other than drinking vodka. When Soviet myth-making was at its height, it was said that the Dinamo sports club, which was controlled by the Ministry of the Interior and ran teams across the USSR, chose blue and white as their colours to represent water and air, the two elements without which man could not live. The truth is rather that Charnock was from Blackburn, and dressed his team in the same colours as the team he supported: Blackburn Rovers.

Further west, the influence was naturally more central European. Lviv was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when, in 1894, it hosted the first football match played on what is now Ukrainian soil, a brief exhibition during a demonstration of sports by the Sokol Sports Club.

By the time a national league was established in 1936, the British were long gone (the expatriate dominance of Soviet football ended in 1908 when Sport, a Russian team, won the Aspeden Cup, the local St Petersburg competition), but the early 2-3-5 lingered as the default. The modification of the offside law in 1925 seems to have made little difference tactically and, with the USSR’s isolation from Fifa restricting meetings with foreign opposition largely to games against amateur sides, there was little to expose how far the Soviets were falling behind.

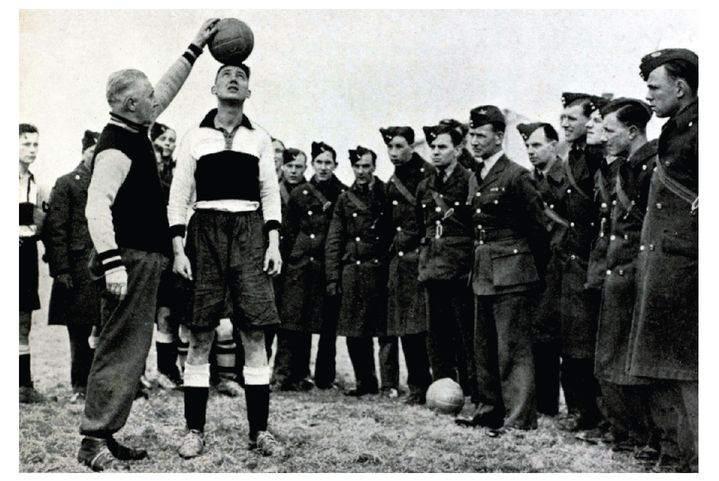

Jimmy Hogan, the father of central European football, demonstrating heading technique to the RAF in France, 1940

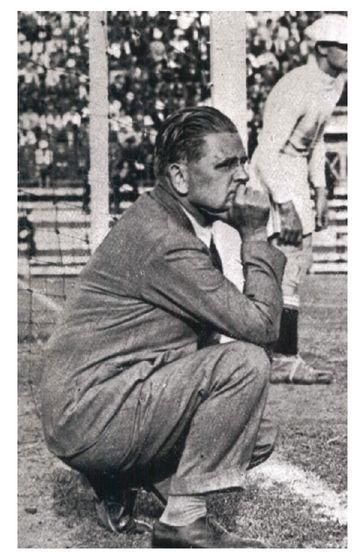

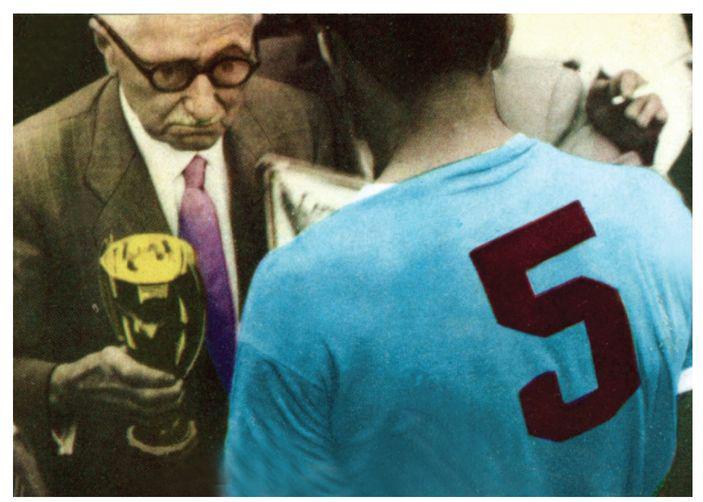

Vittorio Pozzo looks on nervously as Italy beat Czechoslovakia in the 1934 World Cup final

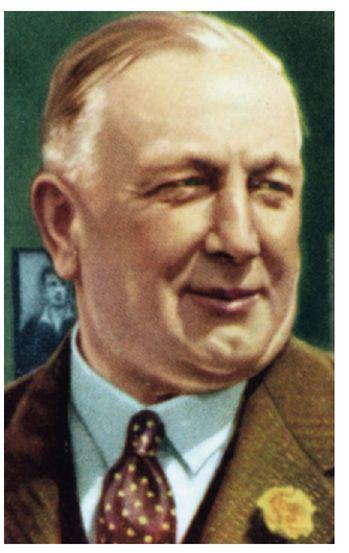

Herbert Chapman, the inventor of the W-M (

all pics © Getty Images

)

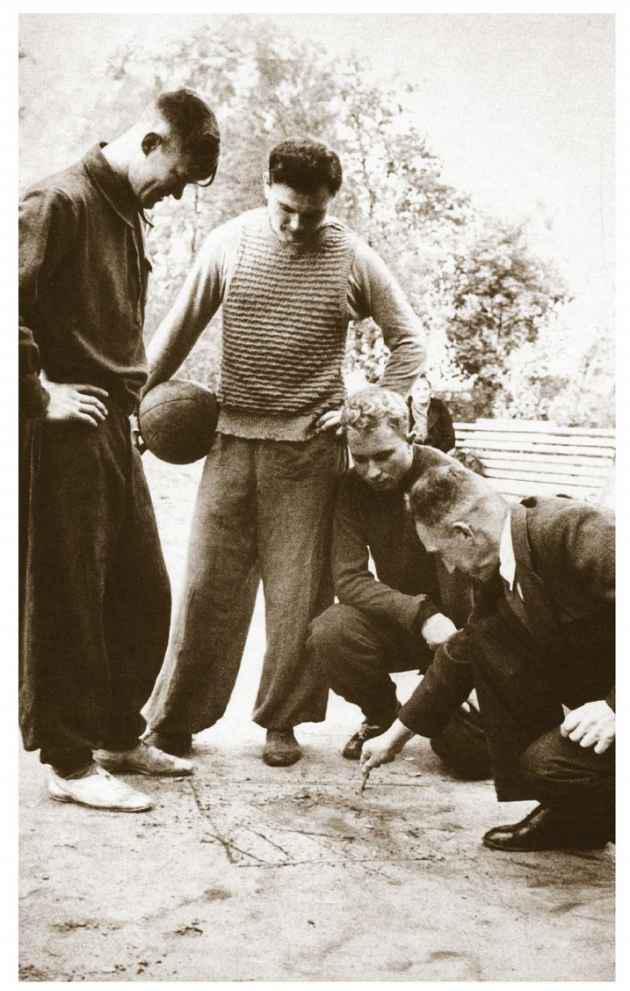

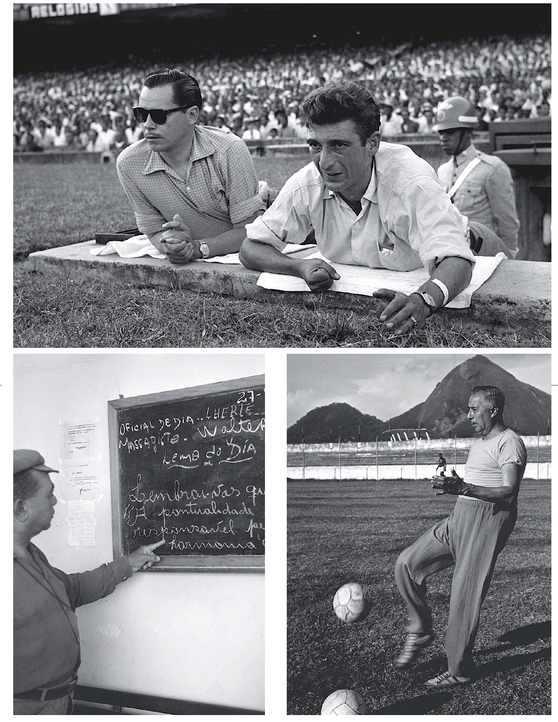

Boris Arkadiev outlines his theory of organised disorder to his CDKA players (

Pavel Eriklinstev

)

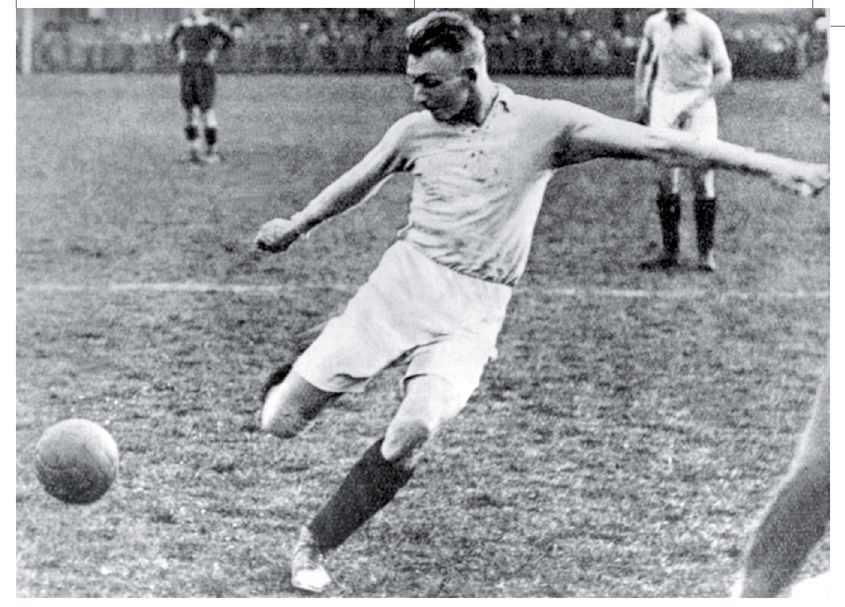

Matthias Sindelar, the withdrawn centre-forward, whose genius lay at the heart of the Austrian Wunderteam

Sándor Kocsis beats Gil Merrick to the ball in Hungary’s 6-3 victory over England at Wembley in 1953 (

both pics © PA Photos

)

Alicide Gigghia beats Moacyr Barbosa at his near post, to win the 1950 World Cup for Uruguay (

PA Photos

)

Jules Rimet hands over the trophy to Uruguay’s captain, Obdulio Varela (

Getty Images

)

Three men who brought tactics to Brazil: Martim Francisco (top), Gentil Cardoso (bottom left) and Fleitas Solich (bottom right) (all pics ©

Arquiro/Agência O Globo

)

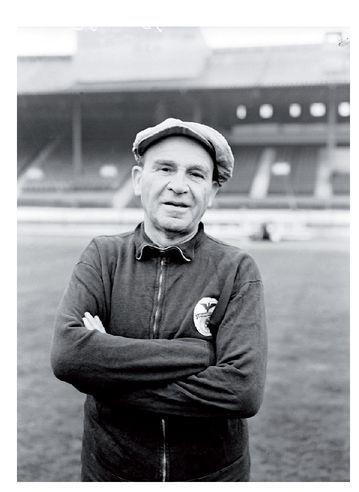

Béla Guttmann, the wandering Hungarian, during his time as coach of Benfica (

PA Photos

)