Jefferson's War (28 page)

Authors: Joseph Wheelan

If the screams didn't awaken them to the fact that they were under attack, the rocket and lit candles unmistakably did. The Tripolitans opened up with their fortress cannons. Crewmen from the two nearby corsairs, both within easy cannon-fire range, peppered the commandos with inaccurate small-arms fire, but the corsairs' cannons, which might have done real damage, inexplicably remained silent.

The

Philadelphia

went up so fast that the flames chased the boarders from below deck, shooting out of portholes and from the spar deck hatchways. The blaze arced into the rigging as the

Americans fled to the

Intrepid,

already beginning to pull away as tongues of fire leaped out at her.

Philadelphia

went up so fast that the flames chased the boarders from below deck, shooting out of portholes and from the spar deck hatchways. The blaze arced into the rigging as the

Americans fled to the

Intrepid,

already beginning to pull away as tongues of fire leaped out at her.

Decatur was the last to leave. He looked around the burning deck one more time and flung himself into the

Intrepid's

rigging. As she swung away, a round from a shore battery whistled through her topgallant sail.

Intrepid's

rigging. As she swung away, a round from a shore battery whistled through her topgallant sail.

The attackers hastened to escape the harbor. In the two boats towing the ketch, the American crewmen strained at their oars, and the

Intrepid's

sweeps also dug deep into the water. The rowers watched flames hungrily lick up the

Philadelphia's

masts receding behind them. The frigate's guns, loaded for harbor defense, suddenly began firing themselves, and, almost as if making a last defiant gesture, she blasted a full broadside into the city.

Intrepid's

sweeps also dug deep into the water. The rowers watched flames hungrily lick up the

Philadelphia's

masts receding behind them. The frigate's guns, loaded for harbor defense, suddenly began firing themselves, and, almost as if making a last defiant gesture, she blasted a full broadside into the city.

Morris described the sight of the burning frigate as “magnificent”; the flames climbing the rigging and masts formed “columns of fire, which, meeting the tops, were reflected into beautiful capitals.” A little later, the frigate's cables gave way and the dying hulk drifted under the bashaw's castle. It burned there all night long.

With seamless precision, the Americans had captured and destroyed a frigate in an enemy harbor, within range of 115 fortress guns and two warships, and escapedâall inside twenty-five minutes, with only one man slightly wounded. They had killed at least twenty enemy soldiers and taken one prisoner. The exploit would have embroidered the record of any commando unit, in any era.

Â

Â

Five miles away on the

Siren,

Stewart watched the

Philadelphia's

topmasts fall. He hadn't gotten into the fight. The

Intrepid's

early embarkation had thrown off the attack timetable. Thirty

Siren

crewmen in two boats had set off for the harbor, only to meet the

Intrepid

as she was heading out to sea. They turned back without getting a chance to damage other enemy ships in the harbor. The two ships met off Tripoli about 1:00 A.M. and set sail together for Syracuse. At daybreak, they were 40 miles away from Tripoli, yet they still could see the light from the burning frigate. The

Philadelphia

burned to the waterline. Her ribs weren't found until 1903.

Siren,

Stewart watched the

Philadelphia's

topmasts fall. He hadn't gotten into the fight. The

Intrepid's

early embarkation had thrown off the attack timetable. Thirty

Siren

crewmen in two boats had set off for the harbor, only to meet the

Intrepid

as she was heading out to sea. They turned back without getting a chance to damage other enemy ships in the harbor. The two ships met off Tripoli about 1:00 A.M. and set sail together for Syracuse. At daybreak, they were 40 miles away from Tripoli, yet they still could see the light from the burning frigate. The

Philadelphia

burned to the waterline. Her ribs weren't found until 1903.

Â

On February 19, lookouts at Syracuse announced the approach of two ships. The quarterdecks of all the squadron's vessels blossomed with field glasses scanning the horizon. To Preble's immense relief, it was the

Intrepid

and the

Siren.

Having received no messages from Stewart and Decatur since they had left Syracuse two weeks before, Preble was full of gnawing fears and questions. At least now they had safely returned. The commodore signaled impatiently, “Have you succeeded?”

Intrepid

and the

Siren.

Having received no messages from Stewart and Decatur since they had left Syracuse two weeks before, Preble was full of gnawing fears and questions. At least now they had safely returned. The commodore signaled impatiently, “Have you succeeded?”

“Yes,” the

Siren

answered.

Siren

answered.

The commandos sailed triumphantly into Syracuse harbor to loud cheers from the crews of the

Constitution, Vixen,

and

Enterprise.

Stewart and Decatur wasted no time in boating to the

Constitution.

They reported to their commander that they had destroyed the

Philadelphia

without losing a single man. While Preble noted later that day in his memo book, with his customary terseness,

“Syren

and

Intrepid

arrived having executed my orders,” he was more fulsome in his praise when reporting to Navy Secretary Smith: “Their conduct in the performance of the dangerous service assigned them, cannot be sufficiently estimatedâIt is beyond all praise.”

Constitution, Vixen,

and

Enterprise.

Stewart and Decatur wasted no time in boating to the

Constitution.

They reported to their commander that they had destroyed the

Philadelphia

without losing a single man. While Preble noted later that day in his memo book, with his customary terseness,

“Syren

and

Intrepid

arrived having executed my orders,” he was more fulsome in his praise when reporting to Navy Secretary Smith: “Their conduct in the performance of the dangerous service assigned them, cannot be sufficiently estimatedâIt is beyond all praise.”

Â

The

Philadelphia

's destruction in Tripoli harbor electrified Europe and America. From the

Victory

off Toulon, Admiral Horatio Nelson called it “the most bold and daring act of the age.” Pope

Pius VII was moved to extol the actions of Decatur and his men: “The American commander, with a small force, and in a short space of time, has done more for the cause of Christianity than the most powerful nations of Christendom have done for ages!”

Philadelphia

's destruction in Tripoli harbor electrified Europe and America. From the

Victory

off Toulon, Admiral Horatio Nelson called it “the most bold and daring act of the age.” Pope

Pius VII was moved to extol the actions of Decatur and his men: “The American commander, with a small force, and in a short space of time, has done more for the cause of Christianity than the most powerful nations of Christendom have done for ages!”

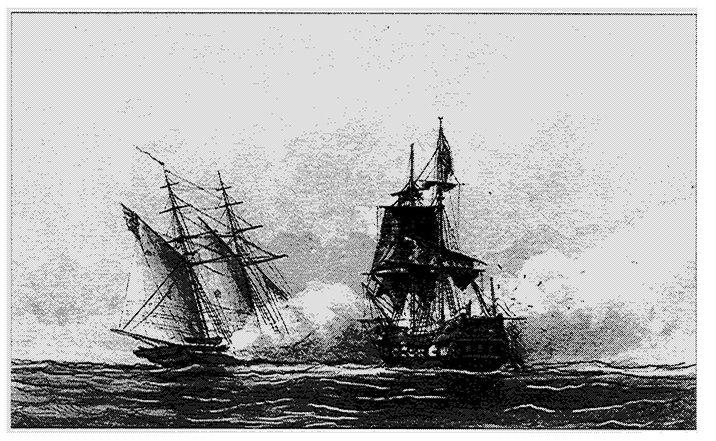

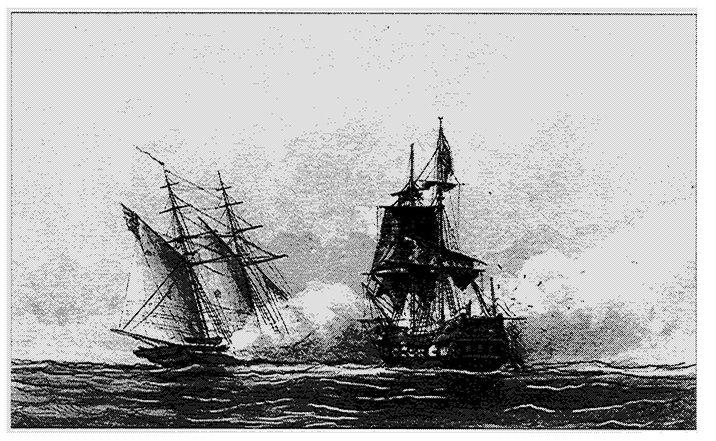

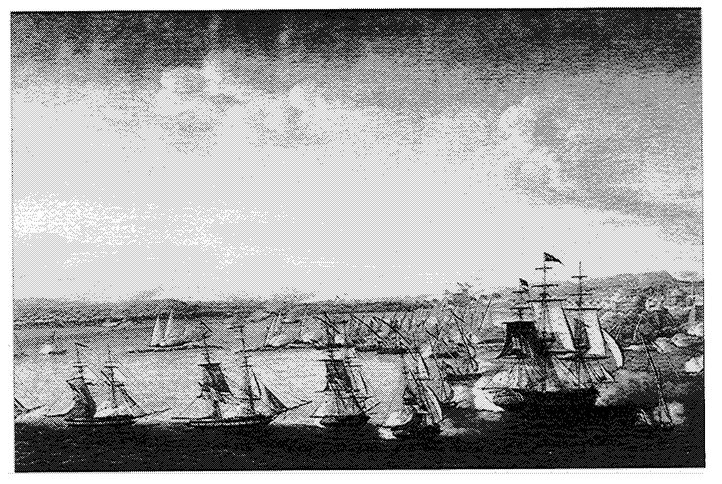

The U.S. Navy schooner

Enterprise

(right) defeats the Tripolitan warship

Tripoli,

on August 1, 1801, in the first battle of the Barbary War. (Naval Historical Center).

Enterprise

(right) defeats the Tripolitan warship

Tripoli,

on August 1, 1801, in the first battle of the Barbary War. (Naval Historical Center).

Lt. Andrew Sterrett, the

Enterprise

commander, was a demanding officer who once ran a seaman through with his sword for cowardice in battle. (Naval Historical Center).

Enterprise

commander, was a demanding officer who once ran a seaman through with his sword for cowardice in battle. (Naval Historical Center).

The U.S. Navy frigate

Philadelphia

ran aground in Tripoli harbor on Oct. 31, 1803. The disaster gave Tripoli a frigate and 307 American prisoners. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia

ran aground in Tripoli harbor on Oct. 31, 1803. The disaster gave Tripoli a frigate and 307 American prisoners. (Naval Historical Center).

Upon surrendering the

Philadelphia,

Capt. William Bainbridge owned the unhappy distinction of having commanded the only two U.S. naval vessels captured during wartime. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia,

Capt. William Bainbridge owned the unhappy distinction of having commanded the only two U.S. naval vessels captured during wartime. (Naval Historical Center).

Commodore Edward Preble, the Barbary War's most effective American naval leader, was dismayed by the loss of the

Philadelphia,

but quickly set into motion plans for her destruction. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia,

but quickly set into motion plans for her destruction. (Naval Historical Center).

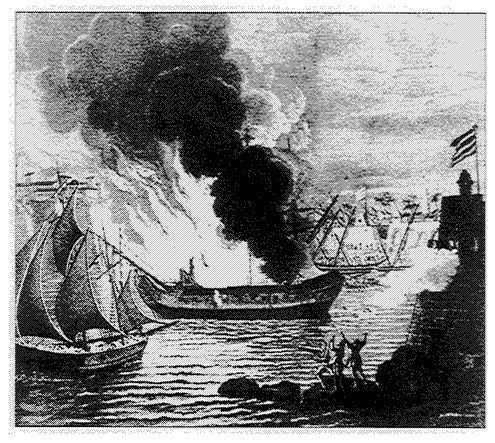

Lt. Stephen Decatur's crew boards the

Philadelphia

before setting her ablaze under the enemy's nose on February 16, 1804. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia

before setting her ablaze under the enemy's nose on February 16, 1804. (Naval Historical Center).

Lt. Stephen Decatur led the daring mission to destroy the

Philadelphia,

becoming an international hero. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia,

becoming an international hero. (Naval Historical Center).

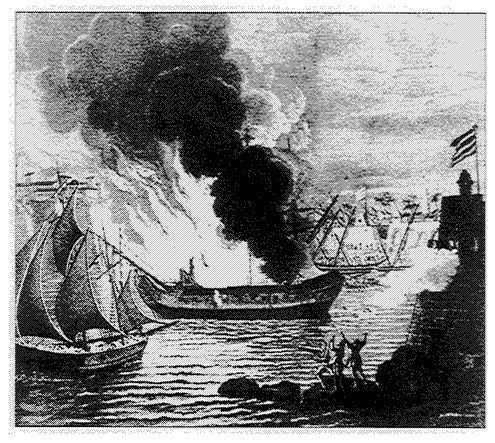

The

Philadelphia

burns in Tripoli harbor. (Naval Historical Center).

Philadelphia

burns in Tripoli harbor. (Naval Historical Center).

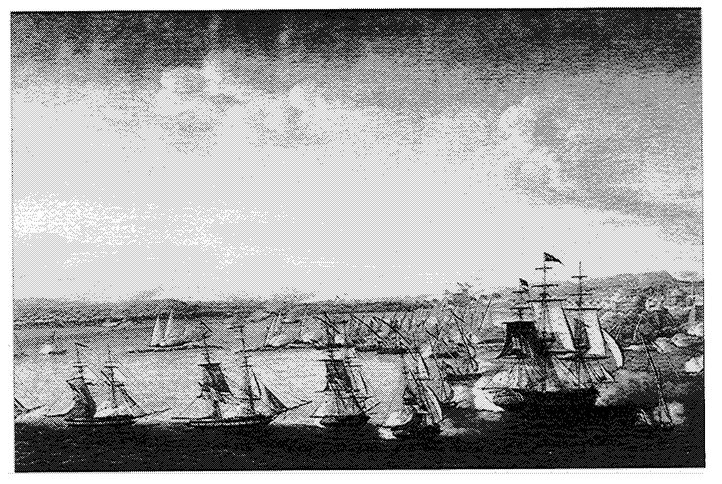

Commodore Preble's squadron enters Tripoli harbor on August 3, 1804, to destroy enemy shipping and fortifications in what became known as the Battle of the Gunboats. (Naval Historical Center).

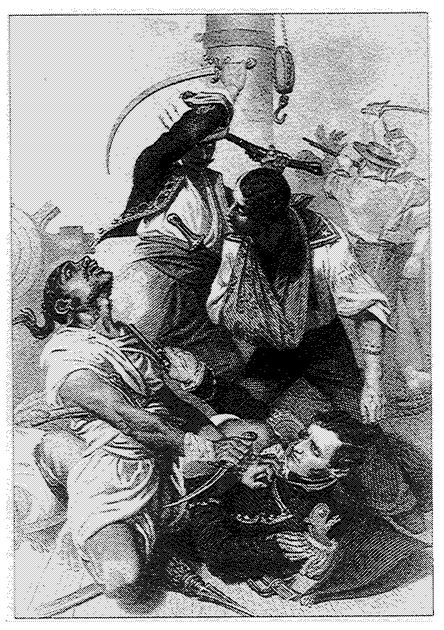

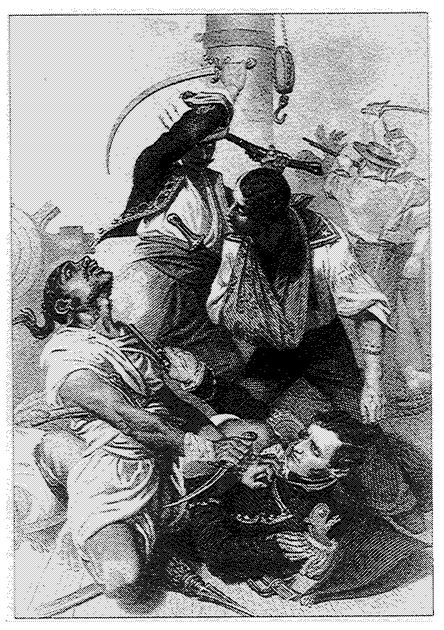

Lt. Stephen Decatur's deadly struggle during the Battle of the Gunboats with the Mameluke captain who Decatur believed fatally wounded his brother, James. (Naval Historical Center).

The fireship

Intrepid

mysteriously exploded September 4, 1804, while on a mission to destroy shipping in Tripoli harbor, killing all 13 crewmen. It was America's last naval offensive of the war. (Naval Historical Center).

Intrepid

mysteriously exploded September 4, 1804, while on a mission to destroy shipping in Tripoli harbor, killing all 13 crewmen. It was America's last naval offensive of the war. (Naval Historical Center).

William Eaton, former U.S. Army captain and consul to Tunis, planned a surprise attack on eastern Tripoli in 1805 with the Tripolitan ruler's deposed brother, Hamet Karamanli. (Naval Historical Center).

Other books

The Language of Secrets by Ausma Zehanat Khan

Babel Found by Matthew James

Holy Device X: Resurrected by Doug Rinaldi

The Player of Games by Iain M. Banks

Second Thoughts by Clarke, Kristofer

Among Thieves by John Clarkson

Atavus by S. W. Frank

Conquerors' Heritage by Timothy Zahn

My Night Breeze (The Breeze Series) by M.L. Newman

Clawback by Mike Cooper