Jefferson's War (29 page)

Authors: Joseph Wheelan

William Eaton (right) and Hamet Karamanli (left) led an invasion force of U.S. marines, dissident Tripolitans, Arabs and European mercenaries 520 miles through the desert to the outskirts of Derna, Tripoli. (Naval Historical Center).

Marine Lt. Presley OâBannon, William Eaton's most trusted officer, planted the Stars and Stripes atop the battlement at Derna, the first American flag-raising on hostile foreign soil. (Naval Historical Center).

Lt. Presley OâBannon's headstone and historical marker in a cemetery in Frankfort, Kentucky. (Photo by Walter Chisholm).

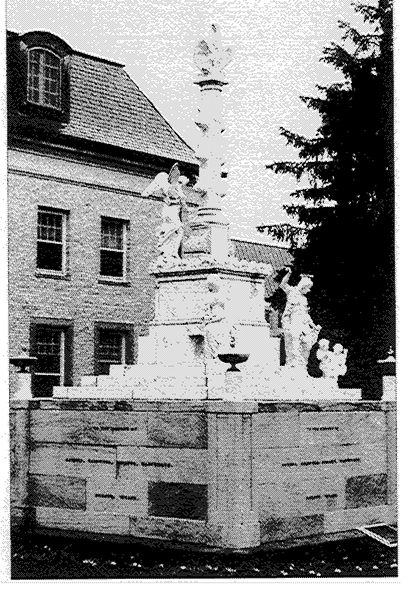

The Tripoli Memorial, the oldest U.S. military monument, dedicated to the six naval officers killed during the Barbary War. It stands behind Preble Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. (Photo by Brian Greenlee).

During a 1949 ceremony, markers were placed at the Tripoli gravesites of five

Intrepid

crewmen. Among those present were (1-r) Captain William Marshall, commander of the USS

Spokane;

Orpay Taft, U.S. consul to Tripoli; Rear Admiral Richard H. Cruzen, division commander; and Joseph Karamanli, Tripoli's mayor and a direct descendant of Yusuf Karamanli, the nation's ruler during the Barbary War. (Naval Historical Center).

Intrepid

crewmen. Among those present were (1-r) Captain William Marshall, commander of the USS

Spokane;

Orpay Taft, U.S. consul to Tripoli; Rear Admiral Richard H. Cruzen, division commander; and Joseph Karamanli, Tripoli's mayor and a direct descendant of Yusuf Karamanli, the nation's ruler during the Barbary War. (Naval Historical Center).

This was what Jefferson had longed for all these twenty years: to show the world the United States was different from the Old World, that it was a nation of dauntless men, that the ship that bore Decatur and his crew to glory was aptly named and embodied the new nation's spirit. He undoubtedly warmed to Consul George Davis's report of the reaction at Tunis: “... it is the only occurrence, which has forced them to view the American character with proper respect.”

In America, Decatur quickly became the new Navy's most celebrated hero. He was promoted to captain over the heads of other, more senior lieutenants, making him at twenty-five the youngest naval officer to hold that rank. Congress commended Decatur formally, awarded him a sword, and rewarded him and his crew with two months' extra pay. A silent play written for the occasion, “Preparations for the Recapture of the Frigate

Philadelphia,

”began with the song “Hail Columbia,” and ended with a procession honoring the

Intrepid

and her crew.

Philadelphia,

”began with the song “Hail Columbia,” and ended with a procession honoring the

Intrepid

and her crew.

Francis Scott Key was moved to pen a song to the tune “To Anacreon in Heaven.” “To Anacreon” was originally composed in the 1770s in Britain by John Stafford Smith for a London gentlemen's drinking club, the Anacreontic Society, to honor its namesake, Anacreon, the convivial bard of ancient Greece. In 1798, Tom Paine wrote different words to the music and called it “Adams and Liberty”; it was a hugely popular political song. Key's new, forgettable lyrics, which appear in his works under the simple title “Song,” were sung at a banquet honoring the

Intrepid

crew. A

decade later, the British attack on Fort McHenry inspired Key to write new lyrics to the old tune. He called it “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One of the verses honoring America's Barbary heroes:

Intrepid

crew. A

decade later, the British attack on Fort McHenry inspired Key to write new lyrics to the old tune. He called it “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One of the verses honoring America's Barbary heroes:

In conflict resistless, each toil they endur'd,

âTill their foes shrunk dismay'd from the war's desolation:

And pale beam'd the Crescent, its splendor obscur'd

By the light of the star-spangled flag of our nation,

Where each flaming star

Gleam'd a meteor of war,

And the truban'd head bowed to the terrible glare,

Now, mixed with the olive, the laurel shall wave,

And form a bright wreath for the brows of the brave.

âTill their foes shrunk dismay'd from the war's desolation:

And pale beam'd the Crescent, its splendor obscur'd

By the light of the star-spangled flag of our nation,

Where each flaming star

Gleam'd a meteor of war,

And the truban'd head bowed to the terrible glare,

Now, mixed with the olive, the laurel shall wave,

And form a bright wreath for the brows of the brave.

Twenty years later, after both Preble and Decatur had died, the question that had long been debated by Navy men in ships' messes and harbor taverns suddenly captured the attention of Congress: Could the

Philadelphia

have been saved? Susan Decatur made the issue timely by filing a claim, as Stephen's widow, to government prize money for the

Philadelphia.

Her claim asserted that the frigate could have been taken intact, and that Stephen Decatur always believed that he could have towed the frigate out of the harbor. Salvador Catalano, the

Intrepid's

pilot, also stated that he believed all along that she was salvageable, and had shared his opinion with Decatur moments before she was burned. But, he said, Preble's orders prevented them from making the attempt.

Philadelphia

have been saved? Susan Decatur made the issue timely by filing a claim, as Stephen's widow, to government prize money for the

Philadelphia.

Her claim asserted that the frigate could have been taken intact, and that Stephen Decatur always believed that he could have towed the frigate out of the harbor. Salvador Catalano, the

Intrepid's

pilot, also stated that he believed all along that she was salvageable, and had shared his opinion with Decatur moments before she was burned. But, he said, Preble's orders prevented them from making the attempt.

Other crew members, however, filed affidavits asserting that it would have been impossible to save the ship. Her sails were unrigged, there was no one to man her, and she was moored near two corsairs and within range of the fortress cannons.

Mediterranean diplomat M. M. Noah urged the government to pay Mrs. Decatur's claim, evidently as a gesture to a naval hero's widow, for he also pointed out that it didn't really matter whether the

Philadelphia

could have been saved or not; America made a stronger statement by burning her.

Mediterranean diplomat M. M. Noah urged the government to pay Mrs. Decatur's claim, evidently as a gesture to a naval hero's widow, for he also pointed out that it didn't really matter whether the

Philadelphia

could have been saved or not; America made a stronger statement by burning her.

Â

The night of the commando attack, the American captives were jarred awake by screaming, shouting, and the rumble of the bashaw's castle cannons. The commotion also awakened the

Philadelphia's

officers at the consul's house, where they flung open the windows facing the harbor and beheld the spectacle of flames swallowing their ship. How it came about remained a great mystery to them all until the next day.

Philadelphia's

officers at the consul's house, where they flung open the windows facing the harbor and beheld the spectacle of flames swallowing their ship. How it came about remained a great mystery to them all until the next day.

At daybreak the next morning, the crewmen's keepers rushed into their prison and began beating everyone they could lay hands on, “hissing like serpents of hell.” As the reason for their fury gradually dawned on the Americans, they could not contain their exultation. Their obvious high spirits over the bashaw's loss of his prize served as a goad to every Tripolitan they encountered. “Every boy we met in the streets would spit on us and pelt us with stones; our tasks were doubled, our bread withheld and every driver exercised cruelties tenfold more rigid and intolerable than before.” Their captors withheld the twice-monthly ration of pork and beef and confined the American officers to their quarters. Cowdery, forbidden to could visit patients, observed, “The Turks appeared much disheartened at the loss of their frigate.”

The bashaw, who had watched her burn from his castle, summoned country militia to the city, expecting a full-scale assault by American troops. The city ramparts were hastily repaired, but when the soldiers tried to mount cannons salvaged from the

burned hulk, the gun carriages broke down and one of the guns exploded, killing and wounding five soldiers.

burned hulk, the gun carriages broke down and one of the guns exploded, killing and wounding five soldiers.

More guards were placed over all the captives, and the officers were summarily moved out of the relative comfort of the consul's home into the castle. Their new home was a large, smoky room illuminated by a single grated skylight. “I have seen the Sea four times in five months,” Bainbridge grumbled to Preble in July 1804. “Close kept under lock & key.”

Six weeks after the raid, Preble returned to Tripoli with the

Constitution

and

Siren

to find out whether the bashaw wished to parley. Yusuf was more intransigent than ever, refusing to exchange prisoners and demanding at least $500,000 for the captives and peace. One reason for the stiff terms was that the Tripolitans believed that Decatur and his commandos had massacred some of the

Philadelphia's

Tripolitan crew. Three bodies had washed up “covered with wounds,” Tripoli's foreign minister, Sidi Mohammed Dghies, informed Bainbridge, asking, “How long has it been since Nations massacred their Prisoners?” The bashaw wanted to question the Tripolitan prisoner in U.S. custody.

Constitution

and

Siren

to find out whether the bashaw wished to parley. Yusuf was more intransigent than ever, refusing to exchange prisoners and demanding at least $500,000 for the captives and peace. One reason for the stiff terms was that the Tripolitans believed that Decatur and his commandos had massacred some of the

Philadelphia's

Tripolitan crew. Three bodies had washed up “covered with wounds,” Tripoli's foreign minister, Sidi Mohammed Dghies, informed Bainbridge, asking, “How long has it been since Nations massacred their Prisoners?” The bashaw wanted to question the Tripolitan prisoner in U.S. custody.

Preble refused to bring the prisoner ashore and said Decatur had reported no massacre. The boarders had fought with edged weapons, and “people who handle dangerous weapons in War, must expect wounds and Death, but I shall never countenance or encourage wanton acts of Cruelty.” Preble also declared that he would sooner sacrifice all the

Philadelphia

prisoners than submit to unfavorable terms. The bashaw forbade Preble to send clothing ashore for the captives; he said such items could only be landed in a neutral vessel.

Philadelphia

prisoners than submit to unfavorable terms. The bashaw forbade Preble to send clothing ashore for the captives; he said such items could only be landed in a neutral vessel.

Preble sailed away and resumed preparations for the summer attacks on Tripoli that he was planning.

XI

PREBLE'S FIGHTING SQUADRON

I find hand to hand is not childs play, âtis kill or be killed.

âCaptain Stephen Decatur, Jr., in a letter to Keith Spence, Philadelphia's purser and father of Midshipman Robert T. Spence

Â

Around me lay arms, legs & trunks of Bodies, in the most mutilated state.âMidshipman Robert T. Spence, in a letter to his mother

Â

Â

Â

August 3, 1804 1:30 p.m.

Â

A

nxious to begin the attack, Commodore Edward Preble scanned the old port of Tripoli through his spyglass from the

Constitution's

quarterdeck. Fair weather had returned after a week of gales. Now his squadron stood before the enemy capital, ready for action. Months of preparation would come together this dayâfor the bashaw as well as Preble. In Tripoli, gun crews manned 115 cannon on the fortress walls, and 25,000 Tripolitan soldiers recruited, trained, and massed for this contingency waited in prepared positions to repel any amphibious landing. From behind the two-mile-long arm of rocks and shoals protecting the harbor waited the alert crews of twenty-four ships and gunboats commanded by Grand Admiral Murad Reis.

nxious to begin the attack, Commodore Edward Preble scanned the old port of Tripoli through his spyglass from the

Constitution's

quarterdeck. Fair weather had returned after a week of gales. Now his squadron stood before the enemy capital, ready for action. Months of preparation would come together this dayâfor the bashaw as well as Preble. In Tripoli, gun crews manned 115 cannon on the fortress walls, and 25,000 Tripolitan soldiers recruited, trained, and massed for this contingency waited in prepared positions to repel any amphibious landing. From behind the two-mile-long arm of rocks and shoals protecting the harbor waited the alert crews of twenty-four ships and gunboats commanded by Grand Admiral Murad Reis.

Other books

How to Dine on Killer Wine: A Party-Planning Mystery by Penny Warner

The Slow Moon by Elizabeth Cox

There May Be Danger by Ianthe Jerrold

Diamond Spirit by Karen Wood

The Thirteen Gun Salute by Patrick O'Brian

This Life: A Novel by Maryann Reid

Good Christian Bitches by Kim Gatlin

The Dangerous Gift by Hunt, Jane

Saint's Sacrament - Sins of the Father by Laveen, Tiana

Crossing the Bridge by Michael Baron