John Aubrey: My Own Life (42 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

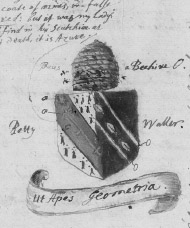

Sir William Petty, knight

27

His horoscope: Monday, Maii 26th, 1623: n h 42' 56" p.m., natus Gulielmus Petty, miles, sub latitudine 51 10' (tempus verum), at Rumsey in Hants.

This horoscope was done, and a judgement made upon it, by Charles Snell, Esq., of Alderholt near Fording-bridge in Hampshire: Jupiter in Cancer makes him fat at heart. John Gadbury also says that vomits would be excellent good for him.

Sir William was the (eldest, or only) son of . . . Petty, of Rumsey in Hampshire, by . . . his wife. His father was born on the Ash Wednesday before Mr Hobbes,

scilicet

1587. He died and was buried at Rumsey 1644, where Sir William intends to set up a monument for him. He was by profession a clothier, and also did dye his own clothes: he left little or no estate to Sir William.

Sir William was born at his father’s house aforesaid, on Trinity Sunday. Rumsey is a little haven town, but hath most kinds of artificers in it. When he was a boy his greatest delight was to be looking on the artificers, e.g. smiths, the watchmaker, carpenters, joiners, etc. and at twelve years old he could have worked at any of these trades. He went to school, and learnt by 12 years a competent smattering of Latin, and was entered into the Greek. He has had few sicknesses. [Aged] about 8, in April very sick and so continued till towards Michaelmas,

About 12 (or 13), i.e. before 15, he has told me, happened to him the most remarkable accident of his life (which he did not tell me), and which was the foundation of all the rest of his greatness and acquiring riches.

He informed me that, about 15, in March, he went over into Normandy, to Caen, in a vessel that went hence, with a little stock, and began to merchandise, and had so good success that he maintained himself, and also educated himself; this I guessed was the most remarkable accident that he meant. He learnt the French tongue, and perfected himself in the Latin, and had Greek enough to serve his turn. Here (at Caen) he studied the arts. Memorandum: he was sometime at La Flèche in the college of Jesuits. At 18, he was (I have heard him say) a better mathematician then he is now: but when occasion is, he knows how to recur to more mathematical knowledge. At Paris he studied anatomy, and read Vesalius with Mr Thomas Hobbes (vide: Mr Hobbes’s life), who loved his company. Mr Hobbes then wrote his

Optiques

; Sir William then had a fine hand in drawing and limning, and drew Mr Hobbes’s optical schemes for him, which he was pleased to like. At Paris, one time, it happened that he was driven to a great strait for money, and I have heard him say that he lived a week on two pennyworth (or 3, I have forgot which, but I think the former) of walnuts.

Quaere: whether he was not sometime a prisoner there?

I remember about 1660 there was a great difference between him and Sir . . ., one of Oliver [Cromwell]’s knights, about . . . They printed one against the other: this knight was wont to preach at Dublin. The knight had been a soldier, and challenged Sir William to fight with him. Sir William is extremely short-sighted, and being the challengee it belonged to him to nominate a place and weapon. He nominated, for the place, a dark cellar, and the weapon to be a great carpenter’s axe. This turned the knight’s challenge into ridicule, and so it came to nought.

He is a person of an admirable inventive head, and practical parts. He hath told me that he hath read but little, that is to say, not since aged 25, and is of Mr Hobbes’s mind, that had he read much, as some men have, he had not known so much as he does, nor should have made such discoveries and improvements.

His physique: his eyes are a kind of goose-grey, but very short-sighted, and, as to aspect, beautiful, and promise sweetness of nature, and they do not deceive, for he is a marvellous good-natured person. Eyebrows thick, dark, and straight (horizontal). His head is very large. He was in his youth very slender, but since these twenty years and more past he grew very plump, so that now (1680) he is

abdomine tardus

.

Robert Boyle

28

The honourable Robert Boyle Esq., the (fifth) son of Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork, was born at Lismor (anciently a great town with a university and 20 churches) in the county of Cork, the 25th day of January anno 1627.

He was nursed by an Irish nurse, after the Irish manner, where they put the child into a pendulous satchel (instead of a cradle), with a slit for the child’s head to peep out.

He learnt his Latin, went to the University of Leyden, travelled in France, Italy, and Switzerland. I have oftentimes heard him say that after he had seen the antiquities and architecture of Rome, he esteemed none ‘anywhere else’. He speaks Latin very well, and very readily, as most men I have met with. I have heard him say that when he was young, he read over Cooper’s dictionary: wherein I think he did very well, and I believe he is much beholding to Cooper for his mastership of that language.

His father in his will, when he comes to the settlement and provision for his son Robert, thus –

Item to my son Robert, whom I beseech God to bless with a particular blessing, I bequeath, etc.

– the greatest part is in Ireland. His father also left him the manor of Stalbridge in Dorset, where is a great freestone house; it was forfeited by the Earl of Castlehaven.

He is very tall (about six foot high) and straight, very temperate, and virtuous, and frugal: a bachelor; keeps a coach; sojourns with his sister, the lady Ranulagh. His greatest delight is chemistry. He has at his sister’s a noble laboratory, and several servants (apprentices to him) to look to it. He is charitable to ingenious men that are in want, and foreign chemists have had large proof of his bounty, for he will not spare for cost to get any rare secret. At his own costs and charges he got translated and printed the New Testament in Arabic, to send into the Mahometan countries. He has not only a high renown in England, but abroad; and when foreigners come to hither, ’tis one of their curiosities to make him a visit.

His works alone may make a library.

General Monck

29

George Monck was born at . . . in Devon (vide: Devon in Heralds’ Office), a second son of . . ., an ancient family which had about Henry VIII’s time 10,000 li. per annum (as he himself said). He was a strong, lusty, well-set young fellow and in his youth happened to slay a man, which was the occasion of his flying into the Low-countries, where he learned to be a soldier.

At the beginning of the late civil wars, he came over to the King’s side, where he had command (quaere: in what part of England?). Anno . . . he was prisoner in the Tower, where his seamstress, Nan Clarges (a blacksmith’s daughter), was kind to him in a double capacity. (The blacksmith’s shop is still of that trade. It is the corner shop, first turning on the right hand as you come out of the Strand into Drury Lane.) It must be remembered that he was then in want and she assisted him. Here she was got with child. She was not at all handsome, nor cleanly. Her mother was one of the five women barbers. Anno . . . (as I remember, 1635) there was a married woman in Drury-lane that had clapt (i.e. given the pox to) a woman’s husband, a neighbour of hers. She complained of this to her neighbour gossips. So they concluded on this revenge, viz. to get her and whip her and shave all the hair off her pudenda; which severities were executed and put into a ballad. ’Twas the first ballad I ever cared for the reading of: the burden of it was thus:

Did yee ever hear the like

Or ever heard the same

Of five women-barbers

That lived in Drury-lane?

(Vide: the Ballad-book)

Anno . . . her brother, Thomas Clarges, came a shipboard to George Monck and told him his sister was brought to bed. ‘Of what?’ said he. ‘Of a son.’ ‘Why then,’ said he, ‘she is my wife.’ He had only this child.

Anno . . . (I have forgot by what means) he got his liberty, and an employment under Oliver Cromwell (I think) at sea, against the Dutch, where he did good service; he had courage enough. But I remember the seamen would laugh, that instead of crying ‘Tack about’, he would say, ‘Wheel to the right (or left)’.

Anno 16 . . . he had command in Scotland (vide: his life), where he was well beloved by his soldiers, and, I think, that country (for an enemy). Oliver [Cromwell], [Lord] Protector, had a great mind to have him home, and sent him a fine complimentary letter, that he desired him to come into England to advise with him. He sent His Highness word that if he pleased he would come to wait upon him at the head of 10,000 men. So that design was spoiled.

Anno 1660, February 10th (as I remember), being then sent for by the Parliament to disband Lambert’s army, he came into London with his army about one o’clock p.m. He then sent to the Parliament this letter, which printed, I annex here. Shortly after he was sent for to the Parliament house, where, in the house, a chair was set for him, but he would not (in modesty) sit down in it. The Parliament (Rump) made him odious to the city, purposely, by pulling down and burning their gates (which I myself saw). The Rump invited him to a great dinner, in February, shortly after, from whence it was never intended that he should have returned (of this I am assured by one of that Parliament). The members stayed till 1, 2, 3, 4 o’clock, but at last His Excellency sent them word he could not come. I believe he suspected some treachery.

Annex: ‘A Letter from his Excellencie the Lord General Monck and the officers under his command to the Parliament; in the name of themselves, and the soldiers under them’, printed by John Macock, 1660.

The honours conferred on George Monck everyone knows.

His sense might be good enough, but he was slow, and heavy. He died Anno . . . and had a magnificent funeral suitable to his greatness.

Dr William Aubrey

William Aubrey, Doctor of Laws

30

: – extracted from a manuscript of funerals, and other good notes, in the hands of Sir Henry St George – I guess it to be the handwriting of Sir Daniel Dun, knight, LL Dr, who married Joane, third daughter of Dr William Aubrey.

William Aubrey (the second son of Thomas Aubrey, the 4th son of Hopkin Aubrey, of Abercunvrig in the county of Brecon) in the 66th year of his age or thereabouts, and on the 25th of June, in the year of our Lord 1595, departed this life, and was buried in the cathedral-church of St Paul in London, on the north side of the chancel, over against the tomb of Sir John Mason, knight, at the base or foot of a great pillar standing upon the highest step of certain degrees or stairs rising into the quire eastward from the same pillar towards the tomb of the right honourable the lord William, Earl of Pembroke, and his funerals were performed the 23rd of July, 1595.

This gentleman in his tender years learned the first grounds of grammar in the College of Brecon, in Brecknock town, and from thence about his age of fourteen years he was sent by his parents to the University of Oxford, where, under the tuition and instruction of one Mr Morgan, a great learned man, in a few years he so much profited in humanity and other recommendable knowledge, especially in Rhetoric and Histories, as that he was found to be fit for the study of the Civil Law, and thereupon was also elected into the fellowship of All Souls College in Oxford (where the same Law hath always much flourished). In which college he earnestly studied and diligently applied himself to the lectures and exercise of the house, as that he there attained the degree of a Doctor of the Law Civil at his age of 35 years, and immediately after, he had bestowed on him the Queen’s Public Lecture of Law in the University, the which he read with so great a commendation as that his fame for learning and knowledge was spread far abroad and he was also esteemed worthy to be called to action in the commonwealth. Wherefore, shortly after, he was made Judge Marshall of the Queen’s armies at St Quentin in France. Which wars finished, he returned into England, and determining with himself, in more peaceable manner and according to his former education, to pass on the course of his life in the exercise of law, he became an advocate of the Arches, and so rested many years, but with such fame and credit as well for his rare skill and science in the law, as also for his sound judgement and good experience therein, as that, of men of best judgement, he was generally accounted peerless in that faculty.