John Quincy Adams (6 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

On March 29, 1778, six weeks after they had left Massachusetts, John Adams and his son sailed into the estuary leading to Bordeaux, when a pilot

came aboard and announced that France and England were at war. On April 1, the Adamses set foot on shore with Jesse Deane, eighteen-year-old William Vernon, and Dr. Noël. Two American merchants, who regularly checked incoming cargoes, took the famed John Adams and his friends for a sumptuous lunch and a tour of the town, a visit to theater before tea and the opera in the evening. Adams marveled at the splendor of French grand opera. “The scenery, the dancing, the music,” he gasped. “Never seen anything of the kind before.”

11

came aboard and announced that France and England were at war. On April 1, the Adamses set foot on shore with Jesse Deane, eighteen-year-old William Vernon, and Dr. Noël. Two American merchants, who regularly checked incoming cargoes, took the famed John Adams and his friends for a sumptuous lunch and a tour of the town, a visit to theater before tea and the opera in the evening. Adams marveled at the splendor of French grand opera. “The scenery, the dancing, the music,” he gasped. “Never seen anything of the kind before.”

11

Adams placed young Vernon with one of the merchants, and on April 4, he set off with his son by carriage for Paris, along with Jesse Deane and a small retinue. Covering 150 miles in only two days, they reached Poitiers in west-central France. “Every part of the country is cultivated,” Adams remarked. “The fields of grain, the vineyards, the castles, the cities, the parks, the gardens, everything is beautiful. Yet every place swarms with beggars.”

12

12

From Poitiers, they rode north to Tours, then east to Orleans and finally Paris, where they checked into an expensive hotel and John Adams put two tired little boys to bed. “My little son,” he wrote in his diary, “has sustained this long journey of nearly 500 miles at the rate of an hundred miles a day with the utmost firmness, as he did our fatiguing and dangerous voyage.”

13

13

After meeting Benjamin Franklin in Paris, John Adams learned to his distress that Jesse Deane's father, Silas, had left for America to present himself to Congress and dispute the charges made about him. Adams would now have to care for Jesse indefinitely.

Putting servants in charge of the boys, Adams followed Franklin on a whirlwind tour of diplomatic receptions at the Palais de Versailles and the châteaus of the ruling French nobilityâthe Duc de Noailles, the Marquis de Lafayette's father-in-law; Prime Minister Comte de Maurepas; and Minister of Foreign Affairs Comte de Vergennes, who took Adams to meet King Louis XVI.

To eliminate the high cost of lodging, Adams moved into a furnished apartment in the Hotel Valentois, a château that Franklin was renting in

Passy, then a small town between Paris and Versailles.

c

Franklin charged Adams no rent and gave him the use of his nine servants as well as his elegant carriage and coachman. Adams enrolled his son and Jesse Deane with Franklin's grandson, nine-year-old “Benny” Bache, in a private boarding school that was near enough to allow John Quincy to spend Sundays with his father. Hardly an intimate occasion, Sunday dinners chez Franklin saw a small army of celebrated figures in the arts and government feasting on a galaxy of delicacies and fine wines from Franklin's cellar of more than 1,000 bottles from renowned French vineyards.

Passy, then a small town between Paris and Versailles.

c

Franklin charged Adams no rent and gave him the use of his nine servants as well as his elegant carriage and coachman. Adams enrolled his son and Jesse Deane with Franklin's grandson, nine-year-old “Benny” Bache, in a private boarding school that was near enough to allow John Quincy to spend Sundays with his father. Hardly an intimate occasion, Sunday dinners chez Franklin saw a small army of celebrated figures in the arts and government feasting on a galaxy of delicacies and fine wines from Franklin's cellar of more than 1,000 bottles from renowned French vineyards.

“He lives in all the splendor and magnificence of a viceroy,” John Adams wrote of Franklin after one Sunday feast, “which is little inferior to that of a king.”

14

14

In addition to Latin and French, the boys learned music, dancing, fencing, and drawing, and within a few weeks, John Quincy spoke fluent French, the universal language of the European upper classes and diplomats everywhere. Not as harsh as many such schools, Monsieur Le Coeur's

Pension

began the school day at 6 a.m. and ended at 7 p.m. but included frequent periods for play to ease the strain of academic discipline.

Pension

began the school day at 6 a.m. and ended at 7 p.m. but included frequent periods for play to ease the strain of academic discipline.

“It was then that the idea of writing a regular journal was first suggested to me,” John Quincy recalled. As he wrote to his mother at the time, “My pappa enjoins it upon me to keep a journal or diary of the events that happen to me, and of objects that I see and characters that I converse with from day to day.” All but breathing his father's thoughts and words, he told his mother,

I am convinced of the utility, importance & necessity of this exercise . . . and although I shall have the mortification a few years hence to read a great deal of my childish nonsense, yet I shall have the pleasure and advantage of remarking the several steps by which I shall have advanced in

taste and judgment and knowledge. I have been to see the palace and gardens of Versailles, the Military School at Paris [Ãcole Militaire] . . . & other scenes of magnificence in and about Paris. . . .

taste and judgment and knowledge. I have been to see the palace and gardens of Versailles, the Military School at Paris [Ãcole Militaire] . . . & other scenes of magnificence in and about Paris. . . .

I am, my ever honored and revered Mamma, your dutiful & affectionate son John Quincy Adams

15

15

Â

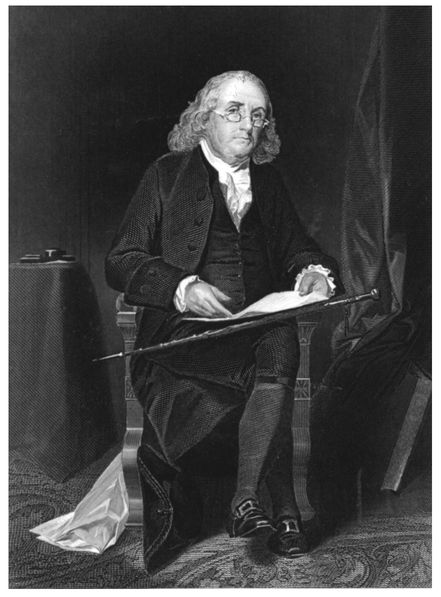

Benjamin Franklin invited John Adams and his eleven-year-old son, John Quincy Adams, to live in his château on the outskirts of Paris after Adams's arrival as one of the American commissioners soliciting financial and military aid from the French government.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

His father's mission to Paris would prove short-lived, however. After barely a month, John Adams wrote to Congress urging the appointment

of Franklin as sole American envoy to France, saying that commissions inevitably generate too many internal frictions to make them effective in international diplomacy.

of Franklin as sole American envoy to France, saying that commissions inevitably generate too many internal frictions to make them effective in international diplomacy.

Â

The Palais de Versailles, where Benjamin Franklin took John Adams to meet French foreign minister Comte de Vergennes.

“The public business has never been methodically conducted,” he grumbled, “and it is not possible to obtain a clear idea of our affairs.”

16

He found his fellow commissioner Arthur Lee argumentative, sharp-tongued, and disagreeable, with a violent temper, and he considered Franklin a dissipated “charlatan,” posing as a philosopher without ever having studied philosophy or the great thinkers. Although Franklin was exceptionally generous, he was a confirmed sybarite, rising late in the morning and, according to Adams, “coming home at all hours.” Franklin, Adams concluded,

16

He found his fellow commissioner Arthur Lee argumentative, sharp-tongued, and disagreeable, with a violent temper, and he considered Franklin a dissipated “charlatan,” posing as a philosopher without ever having studied philosophy or the great thinkers. Although Franklin was exceptionally generous, he was a confirmed sybarite, rising late in the morning and, according to Adams, “coming home at all hours.” Franklin, Adams concluded,

has a passion for reputation and fame as strong as you can imagine, and his time and thoughts are chiefly employed to obtain it, and to set tongues and pens, male and female, to celebrating him. Painters, statuaries, sculptors,

china potters and all are set to work for this end. He has the most affectionate and insinuating way of charming the woman or the man that he fixes on. It is the most silly and ridiculous way imaginable, in the sight of an American, but it succeeds to admiration, fulsome and sickish as it is, in Europe.

17

china potters and all are set to work for this end. He has the most affectionate and insinuating way of charming the woman or the man that he fixes on. It is the most silly and ridiculous way imaginable, in the sight of an American, but it succeeds to admiration, fulsome and sickish as it is, in Europe.

17

With Franklin pursuing his rich social life, few diplomatic reports had flowed from Paris to Congress, and Adams assumed the burden of combing through hundreds of accumulated documents and condensing them into a series of reports that left him with too little time to enjoy Paris or, for that matter, get enough sleep. All but dismissed by a loyalist acquaintance as “a man of no consequence,” the work-oriented Adams seemed “out of his element” in the world of diplomacyâespecially in Paris.

“He cannot dance, drink, game, flatter, promise, dress, swear with the gentlemen and talk small talk or flirt with the ladies. In short, he has none of the essential arts or ornaments which constitute a courtier,” one of his friends remarked.

18

Adams himself admitted, “I am wearied to death with gazing wherever I go at a profusion of unmeaning wealth and magnificence. Gold, marble, silk, velvet, silver, ivory, and alabaster make up the show everywhere.”

19

18

Adams himself admitted, “I am wearied to death with gazing wherever I go at a profusion of unmeaning wealth and magnificence. Gold, marble, silk, velvet, silver, ivory, and alabaster make up the show everywhere.”

19

In March 1779, eleven months after they had arrived in France, John Quincy and his father were elated to begin their trip home to America, taking a coach from Paris to Nantes, where the Loire estuary empties into the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic Ocean. Franklin agreed to care for Jesse Deane and relieve John Adams of that responsibility.

Few ships sailed or docked on schedule in a world at war, and their ship, the

Alliance,

was not in port. The two Adamses spent the next seven weeks seeing the countryside, reading books, writing letters, attending theater, concerts, and operas, and visiting the castlelike home of Maryland merchant Joshua Johnson, his English wife, Catherine, and their three little girls. Adams had befriended Johnson's brother, Maryland governor Thomas Johnson, at the Continental Congress, establishing a tie that would bind the two families for the rest of their lives.

Alliance,

was not in port. The two Adamses spent the next seven weeks seeing the countryside, reading books, writing letters, attending theater, concerts, and operas, and visiting the castlelike home of Maryland merchant Joshua Johnson, his English wife, Catherine, and their three little girls. Adams had befriended Johnson's brother, Maryland governor Thomas Johnson, at the Continental Congress, establishing a tie that would bind the two families for the rest of their lives.

On April 22, the

Alliance

arrived at Nantes, and the Adamses all but leaped aboardâonly to be told to disembark. The vessel would not sail to America because the French government had assigned it to John Paul Jones's squadron to harass British shipping in the English Channel. “This is a cruel disappointment,” Adams railed in his diary.

Alliance

arrived at Nantes, and the Adamses all but leaped aboardâonly to be told to disembark. The vessel would not sail to America because the French government had assigned it to John Paul Jones's squadron to harass British shipping in the English Channel. “This is a cruel disappointment,” Adams railed in his diary.

A few days later, the Adamses traveled westward along the southern shore of Brittany to the port of Lorient, where they were told they were more likely to find a ship bound for America. What they found were weeks of boredom in a town devoid of culture. The highlights of their stay were several dinners with John Paul Jones and a visit to his ship, the

Bonhomme Richard

âonce a decrepit French ship that Jones had refitted with forty-two guns and renamed in Franklin's honor.

d

Bonhomme Richard

âonce a decrepit French ship that Jones had refitted with forty-two guns and renamed in Franklin's honor.

d

On June 17, three months after leaving Paris, John Quincy and his father boarded the French frigate

Sensible

in Lorient, along with the first French ambassador to the United States, the Chevalier de la Luzerne, and his aide, the Marquis François de Barbé Marbois. In what proved a smooth, uneventful crossing, John Quincy Adams displayed both his language skills and his pedagogical skills absorbed from teachers at his French school, as he succeeded in teaching the two French diplomats to speak serviceable Englishâin just eight weeks.

Sensible

in Lorient, along with the first French ambassador to the United States, the Chevalier de la Luzerne, and his aide, the Marquis François de Barbé Marbois. In what proved a smooth, uneventful crossing, John Quincy Adams displayed both his language skills and his pedagogical skills absorbed from teachers at his French school, as he succeeded in teaching the two French diplomats to speak serviceable Englishâin just eight weeks.

“The Chevalier de la Luzerne and Mr. Marbois,” John Adams beamed, “are in raptures with my son.”

I found them this morning, the ambassador seated on a cushion in our state room, Mr. Marbois in his cot at his left hand and my son stretched out in his at his rightâthe ambassador reading out loud in

Blackstone's

Discourse

. . . and my son correcting the pronunciation of every word and syllable and letter. The ambassador said he was astonished at my son's knowledge; that he was a master of his own language like a professor. Mr. Marbois said “your son teaches us more than you. He shows us no mercy. We must have Mr. John.”

20

Blackstone's

Discourse

. . . and my son correcting the pronunciation of every word and syllable and letter. The ambassador said he was astonished at my son's knowledge; that he was a master of his own language like a professor. Mr. Marbois said “your son teaches us more than you. He shows us no mercy. We must have Mr. John.”

20

The

Sensible

reached Boston at the beginning of August 1779, and John Adams had no sooner stepped ashore than his friends, neighbors, and family elected him to a special convention to draft a constitution for Massachusetts. The convention, in turn, asked him to draft the document himself, and drawing from his brilliant

Thoughts on Government

, he wrote most of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. Beginning with a bill of rights, it placed all political power in the hands of the people and guaranteed such “natural, essential, and unalienable rights” as free speech, a free press, and free assembly. It also guaranteed free elections and the right of freemen to trial by jury and to protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, the right to keep and bear arms, the right to petition government for redress of grievances, and “the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties” and “of acquiring, possessing, and protecting their property.”

21

Sensible

reached Boston at the beginning of August 1779, and John Adams had no sooner stepped ashore than his friends, neighbors, and family elected him to a special convention to draft a constitution for Massachusetts. The convention, in turn, asked him to draft the document himself, and drawing from his brilliant

Thoughts on Government

, he wrote most of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. Beginning with a bill of rights, it placed all political power in the hands of the people and guaranteed such “natural, essential, and unalienable rights” as free speech, a free press, and free assembly. It also guaranteed free elections and the right of freemen to trial by jury and to protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, the right to keep and bear arms, the right to petition government for redress of grievances, and “the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties” and “of acquiring, possessing, and protecting their property.”

21

When John Adams had blotted the ink at the end of his draft, word arrived from Congress that, based on his recommendations, it had dissolved the commission in Paris in favor of a single ambassador, but instead of Franklin, it voted unanimously to appoint him, John Adams, to fill the post.

Seventy-one days after landing in Boston, Adams and his son boarded the same ship that had brought them home, the

Sensible

, and sailed for France for the second time in a year.

Sensible

, and sailed for France for the second time in a year.

“My habitation, how disconsolate it looks!” Abigail raged at her husband. “My table, I set down to it but cannot swallow my food. O why was I born with so much sensibility and why possessing it have I so often been called to struggle with it?”

22

22

Other books

Elisha Magus by E.C. Ambrose

Meghan: A Sweet Scottish Medieval Romance by Tanya Anne Crosby, Alaina Christine Crosby

Swallow the Air by Tara June Winch

The Library of Shadows by Mikkel Birkegaard

Even Odds by Elia Winters

Darkhouse (Experiment in Terror #1) by Halle, Karina

Embracing the Wolf by Felicity Heaton

This Boy's Life by Wolff, Tobias

Mystic Flame (Beyond Ontariese 4) by Cyndi Friberg